[ad_1]

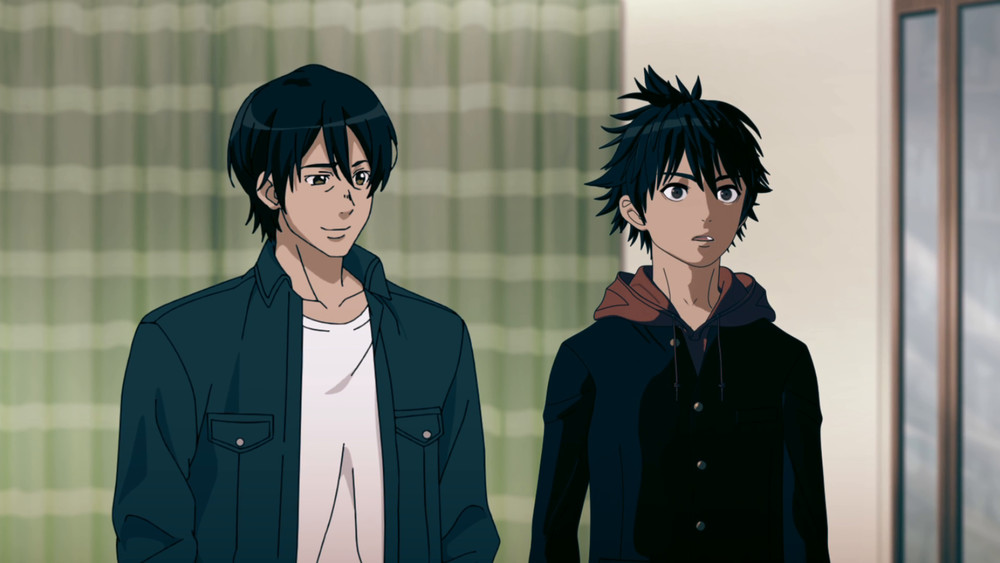

During San Diego Comic Con 2021, fans were given a first look at two new 3DCG anime entries into established franchises. The first was Dragon Ball Super: Super Hero, debuting with a short look at Goku’s new character model and the style of animation we could expect to see. Mangaka Akira Toriyama had already prepped us back in May by revealing that the film would be “charting through some unexplored territory in terms of the visual aesthetics”, and while there’s been some skepticism about the amount of frames, the feedback to the teaser has been generally positive.

But on the other hand, the reaction to Blade Runner: Black Lotus‘ first trailer has been anything but. At time of writing, the YouTube upload currently sits at 40% dislikes, with plenty of comments ranging from, “Damn this trailer killed any anticipation I had for this show” to “This looks like an expansion to The Sims 4”. These kinds of reactions aren’t new to animation studio Sola Digital Arts. Last year, Ghost in the Shell: SAC_2045 faced similar backlash. Anime fans are frequently regarded as being “Anti-3D”, but clearly this disdain isn’t equally distributed.

The fact that there are more CG series overall these days also means that there are more opportunities for disappointment. While 3D will likely never overtake hand-drawn series, overproduction has forced their numbers to surge. There are so many 2D series being produced that producers have been seeking out new ways to get their shows created. Netflix has famously been expanding their definition of “anime” to include works from South Korea’s Studio Mir and the United States’ Lex and Otis, but this has also meant moving towards 3D options as well.

Even companies that would usually develop VFX for live-action films or animate video game cutscenes are now being asked to create full TV series and feature films. Sometimes this can work out, like with the generally well-received Altered Carbon Resleeved by Fire Emblem Heroes animation studio Anima. But sometimes a desperate search for content can get you an Ex-Arm.

Finding out how to create appealing 3D anime is a long process—it’s not just about technical skill. Polygon Pictures had been creating popular cartoons for US audiences before they began creating anime in 2014. However, despite their award-winning track record with shows like Star Wars: The Clone Wars and Transformers Prime, many complained that Knights of Sidonia‘s first season felt choppy, like a video game struggling to load. As company president Shuzo John Shiota admits, it’s an evolving process at the studio, and thus Polygon Pictures shows in 2021 have managed to avoid the typical backlash.

For other teams like Orange, studio president Eiji Inomoto had a head start, having first started creating anime-style CG for ZOIDS: Chaotic Century back in 1999. He once stated that he feels that much of his work is done while fighting the audience’s impulse to reject CG. Similarly, despite the popularity of realistic approaches at the time, Sanzigen president Hiroaki Matsuura wanted to create CG anime that could appeal to fans of 2D animation in Japan.

CG anime studios use a number of methods to emulate the appeal of 2D animation. The first and most obvious is toon shading. Used as a tool in animation all over the world, toon shading rejects realistic light dispersion in favour of hard shadows and flat colors. This is the approach taken by the Dragon Ball Super: Super Hero team, as it was effective in the previous films as well.

However, the most divisive production technique used within 3D anime and anime-style games is what is sometimes called “frame dropping”. One of the most recognizable aspects of Japanese animation is that it’s limited. Rather than there being a new drawing every frame, animators will instead change the frequency of the drawings depending on the movement.

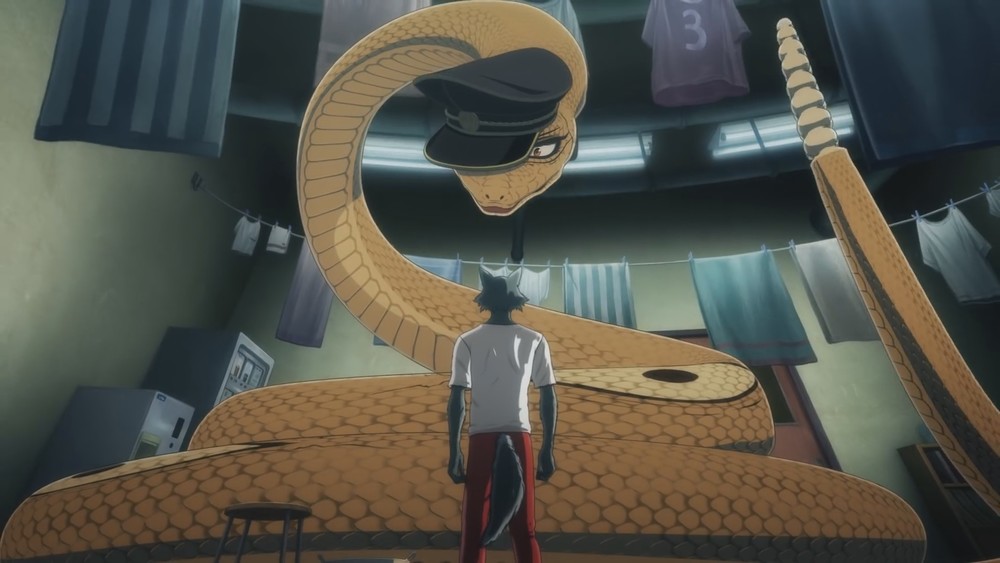

While some see this as a downside of anime, it’s also a stylistic advantage. Arc System Works technical artist Junya Motomura emphasizes that by matching a 2D workflow on Guilty Gear Xrd, each key pose has a lot more impact and they can get away with breaking the rules of 3D to achieve this. One case of rule breaking is what Sanzigen animator Masanori Uetaka refers to as “disintegration”. This is when an animator will distort a character model to create a certain type of pose or expression within the final product.

An example of “disintegration” on BBK/BRNK.

However, not every studio creates anime the same way. In fact, not every 3D animation studio in Japan was built to create animation for audiences in Japan. While Shinji Aramaki‘s Appleseed film is closer to what we’d generally refer to as “anime”, his subsequent works at Sola Digital Arts have strayed stylistically from that definition. The Blade Runner: Black Lotus studio was initially established to create the direct-to-video animated film Starship Troopers: Invasion. With issues funding future live-action films, Sony Pictures asked the Starship Troopers team to explore the lower-budget option of creating an animated sequel to Paul Verhoeven’s classic. It helped that director Shinji Aramaki was already a fan.

Their approach made sense at the time: 3D animation was a hard sell for anime fans, so the company spent the last decade relying on contracts with a focus on American audiences. Appleseed Alpha was released in the United States first, based on a script by American video game writer Marianne Krawczyk while Starship Troopers: Traitor of Mars was yet another direct-to-video release for fans of the original property.

There are frequent discussions about what does and doesn’t count as anime, but it’s a term that Sola Digital Arts was avoiding until they were asked to make “Netflix Original Anime”. Yet by this point, other CG anime studios had already worked out how to develop shows that appealed to existing fans. Polygon Pictures‘ BLAME! and Orange‘s Land of the Lustrous are still brought up today as examples of how CG anime should look.

On the other hand, Sola hadn’t felt the need to explore anime-style toon shading, hand-drawn effects or frame dropping in their Starship Troopers work. Therefore, Ultraman, Ghost in the Shell: SAC_2045, and the new Blade Runner: Black Lotus are all more akin to video game cutscenes than the work of their anime industry contemporaries.

It doesn’t help that we’d already seen a sneak peek at what a Blade Runner anime could’ve looked like. Shinichiro Watanabe‘s Blade Runner: Black Out 2022 was a visual marvel, capturing the original film’s cyberpunk aesthetic within stunning 2D animation from some of Japan’s best creatives. It was only 10 minutes long, but fans still remember it fondly four years later. Black Lotus was greenlit to follow up from this short film, but created by an entirely separate team. While Watanabe is listed as “creative producer”, he clarified that he only provided his opinions on the early concept. The rest will be handled by the directing team of Shinji Aramaki and Kenji Kamiyama.

For many, Sola Digital Arts‘ latest releases have been a disappointment. Both are sequels to beloved 2D works that no longer have any resemblance to the originals. On the other hand, Dragon Ball Super: Super Hero is still exciting because we’ve already seen that they aim to keep the visuals familiar. Rather than making CG animation aimed at the US market, Toei Animation is one of the earliest anime studios to experiment with bringing their iconic characters to 3D. In 1999, Mamoru Hosoda directed a CG GeGeGe no Kitarō short, and in 2000, a CG short titled Digimon Grand Prix. More recently, the studio released Hugtto! Precure Futari wa Precure All Stars Memories in 2018, winning the CGWorld Award for best CG Animation that year.

The point is, studios like Toei Animation have had a long head start on Sola Digital Arts in creating anime-style CG. While fans have been quick to decry all 3D anime, more exceptions are released every year as a result of decades of animation research and healthy pre-productions. Ultimately, no matter how much we might kick and scream, we don’t actually hate 3D anime. But we do have high expectations for it.

[ad_2]