[ad_1]

October 30, 2021

·

0 comments

By Tom Wilmot.

The height of the tokusatsu (special-effects) era in 1960s Japan is best remembered for the slew of giant monster movies that dominated cinemas. Studio Toho’s titanic Godzilla franchise topped the box office, while competitor Daiei found success with the Gamera and Daimajin series. However, while kaiju made the headlines, this period also saw the production of many, more modestly budgeted tokusatsu films that have since slipped through the cracks of Japanese cinema history. One such film is 1968’s The Snake Girl and the Silver-Haired Witch, from director Noriaki Yuasa. Telling a twisted horror tale from the mind of legendary manga author Kazuo Umezu, the film is a charming, small-scale spook-fest that’s an anomaly of sorts in the world of Japanese horror cinema.

Having lived in a Christian orphanage for most of her life, Sayuri (Yachie Matsui) is finally found and adopted (or rather, re-adopted) by her birth parents. However, soon after arriving at her new home, supernatural happenings convince the girl that something is afoot. Her suspicions are proven correct in the form of a mysterious sister, Tamami (Mayumi Takahashi), who’s been hidden in the family attic for God knows how long. The reptilian-like child torments the innocent Sayuri, who begins to suspect that her newly found sister may be more than just a little girl.

Snake Girl is presented as more of a fable than a run-of-the-mill horror, which is unsurprising given the material it’s based on. Loosely adapted from various manga stories from Kazuo Umezu, which are collected in English under the title Reptilia, the film plays out like a modern fairy tale as seen from a child’s perspective. Poor Sayuri is subjected to increasingly brutal treatment at the hands of Tamami and the titular Silver-Haired Witch and is left questioning how much of what’s happening to her is real. We’re left to ponder whether her suspicions that Tamami is a shape-shifting snake are well-founded or if they’re the result of an exaggerated, childlike imagination. The ambiguity concerning the true nature of both villains is what makes the film’s central mystery so gripping and is why repeat viewings are so rewarding.

Remarkably, as revealed in the supplementals, Yachie Matsui and Mayumi Takahashi would never star in a major feature again after their starkly contrasting roles in Snake Girl. This is most surprising given that the two are wonderful as the opposing sisters, each bringing a natural innocence to challenging roles. One only has to look at some of the child performances in some of Daiei’s Gamera films to know that decent child-actors were hard to come by, so the fact that the two never performed for the studio again is rather strange. That being said, the fact that Snake Girl marks their only screen credit adds to the cult-movie feel. While touching on performances, it’s always worth noting an appearance from the wonderful Kuniko Miyake, whose brief appearance as Sister Yamakawa is as enjoyable as any other from the prolific actress.

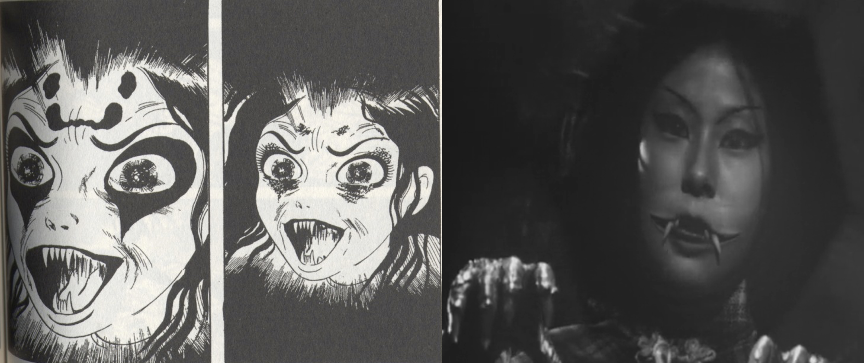

Director Yuasa was no stranger to tokusatsu films, having helmed the first four entries in the Gamera series before working on Snake Girl. It’s no surprise then that the special effects-heavy scenes are some of the most enjoyable in the film. Giant, swirling spirals mark the start of ghostly dream sequences, during which Sayuri finds herself attacked by sentient limbs and shape-shifting snakes. Even some of the less subtle visual tricks, notably any involving puppets, manage to come across as spooky, thanks to shadowy cinematography that evokes classic horror aesthetics. Impressive also is the snake-like makeup used to bring Tamami’s nightmarish animal form to life. The majority of the effects have held up remarkably well, and even those that have aged poorly add to the film’s charm, allowing for some surreal imagery.

Snake Girl occupies a strange space where it isn’t quite child-friendly enough to be fun, family viewing, but is also too goofy to be considered a truly adult horror. Perhaps it’s this unspecified target audience and tone that make the film such an appealing oddity. The tonal imbalances, dashes of violence, and plot inconsistencies all make Snake Girl an enjoyable mess that follows some semblance of dream logic. Along with several supernatural instances that don’t quite add up, the shot composition and framing often defies rational sense where the narrative is concerned. Such quirks only add to the joy of watching of the film as, once logic is thrown out the window, it’s near impossible to predict what crazy twist is coming next.

The question of where Snake Girl fits into the broader library of Japanese horror cinema is something film historian David Kalat explores as part of his highly entertaining audio commentary. Stacking the film up against similar tokusatsu releases and the later J-Horror films of the 1990s and after, Kalat discusses how Yuasa’s feature is in a league of its own despite featuring aspects of several horror sub-genres. The historian’s love for Snake Girl shines through in everything from his enthusiasm for the film’s goofiness to the way he refers to glaring plot holes as no more than “narrative ambiguities.” Carefully structured and very informative, Kalat’s commentary is as fun to listen to as the film is to watch and is a welcome addition to Arrow’s package.

Also chiming in on this release with an excellent introduction to both the work of Kazuo Umezu and tokusatsu cinema in general is Zack Davisson. The manga and folklore scholar provides insight into Umezu’s rise to be Japan’s foremost author of horror manga and touches on how the writer’s involvement in Snake Girl’s screenplay may be the reason behind some credit confusion abroad. Davisson’s encyclopaedic knowledge of Japanese folklore and its place in popular media is the lifeblood of this featurette, as we’re presented with a comprehensive overview of the origins of horror manga. Overall, this is an engaging thirty-minute crash course on the post-war Japanese popular culture climate that allowed Snake Girl to be made.

Rounding out Arrow’s package is a written essay from author Raffael Coronelli, whose reading of Snake Girl introduces ideas surrounding the Japanese occult. More specifically, Coronelli brings to light Yuasa’s fascination with folklore creatures as well as the director’s belief in films having animal characters that have “concrete and complex motivations”. The author outlines the chilling link between the history of the snake yokai, hebi-tsuki, and the motivations behind the various attacks Sayuri is subjected to.

The Snake Girl and the Silver-Haired Witch is one of those rare horror films that manages to appeal to everyone while targeting no one in particular. While just one of many tokusatsu films to be churned out by studio Daiei in the 1960s, its release is a welcome addition to Arrow Video’s growing catalogue of goofy Japanese horror films. You can pick the bones of the various plot holes, aged effects, and tonal inconsistencies, or you can gleefully indulge in what is a delightful and distinct piece of classic horror cinema.

The Snake Girl and the Silver-Haired Witch is released on UK Blu-ray by Arrow Video.

[ad_2]