[ad_1]

By Andrew Osmond.

The four Code Geass feature films being released by Anime Limited amount to a hybrid, a kind of hybrid that’s common in anime, but with an unusual twist. Let me explain, although many Code Geass fans can skim the next few paragraphs.

Of the four films, the first three – subtitled Initiation, Transgression and Glorification – were released in Japanese cinemas within seven months. They’re a three-part retelling of the Code Geass TV series (including its second season, called “R2”), which ran from 2006 to 2008. The films include lots of animation from the TV series, but interspersed with new scenes and other changes. I wrote an article on the first film, Initiation, where I went through the particular changes it made.

On the whole, though, the three films keep to the big story points of the original series, from start to finish. However, there’s one big exception. In the TV show, one of the main supporting characters – Geass fans will know which one – went through an elaborate extended plotline, full of pain and trauma. This long plotline culminated in the character’s death midway through the story, a moment no fan of the TV Code Geass would forget.

However, in the Code Geass films, that whole twisty plotline is removed. Moreover, the films emphasise that the relevant character doesn’t die in the new version. The said person appears in newly-animated scenes, long after the point where the character died in the TV continuity. It would have been easy for the films to have disposed of the character another way, but that doesn’t happen.

Indeed, the character also appears in the fourth of the Geass films, Code Geass: Lelouch of the Re:surrection. Unlike its predecessors, Re:surrection isn’t a TV remake. It’s a completely new continuation of the Geass story… but which story is it continuing? In fact, the point of keeping the character alive is to show Re:surrection is not actually a sequel to the TV version of Code Geass. Instead, Re;surrection is a sequel to the first three Geass films, which show a slightly different universe to the TV version.

Why do something so strange? The answer is linked to the conclusion of the TV Code Geass (largely replicated at the end of Glorification), which was unusually final by anime standards. In 2018, Anime News Network quoted a comment by Code Geass’s writer, Ichiro Okouchi. “At the time of the television series,” he said, “I intended to close the book on Lelouch’s story after the final episode. However, this film, Glorification, is a little different. It wasn’t intended to be an end but a beginning.”

According to Anime News Network, the Code Geass director Goro Taniguchi added that “the differences in story in the film trilogy [that is, Initiation, Transgression and Glorification] are not a negation of the television series, but rather one possible outcome.” In other words, Taniguchi and Okouchi wanted their TV end to Code Geass to stay standing.

From the standpoint of the TV version, the Re;surrection film is non-canon, a “what-if?” story – while, of course, still providing Code Geass fans with a sequel. If you want an equivalent, think of the original Sherlock Holmes stories. The detective’s creator, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, killed the Great Detective at Reichenbach Falls in the story, “The Final Probelem.” However, fan demand forced Doyle to resurrect Holmes in a story called “The Empty House.”

What Lelouch of the Re;surrection does is a bit like if Doyle had begun “The Empty House” with the disclaimer that this was an imaginary story, written by Sherlock’s friend Doctor Watson. Or, as Alan Moore playfully put it in an apocalyptic “final ever” Superman comic strip published in the 1980s, “This is an IMAGINARY STORY… Aren’t they all?”

The meta-sleight in the Code Geass films is unusual, but the practice of adapting anime TV series for feature films is nearly sixty years old. Like many common anime practices, the way it was done came from penny pinching. In the 1960s, most young anime studios had extremely low budgets.

In America, the Hanna-Barbera studio is often described as making cheap cartoons, including its early TV hits, Yogi Bear and The Flintsones. Yet when Hanna-Barbera adapted both series for the cinema, it could afford to make new stories for the TV characters, with upgraded visuals for the big screen. The films were Hey There, It’s Yogi Bear! in 1964 and The Man Called Flintstone in 1966.

Between them, Japan released its own first film from a TV anime. Astro Boy: The Brave in Space was released to cinemas in 1965, but it may not have had any new animation of its own. Rather the film was compiled from three TV episodes. Bizarrely, while much of the film in in black and white, like the TV series, some portions are colourised. Other bits are partly colourised; at one point a monochrome Astro Boy flies against a red background.

Soon editing anime TV series to make “movies” was a common practice, though without the weird colour transitions of the Astro Boy film. In 1970, for example, there were three hour-long films edited from the girls’ volleyball series Attack No. 1, and two from the baseball series Star of the Giants.

Many of the early film edits weren’t released as stand-alone films. Rather, they were shown in double-bills, or in miscellaneous packages for children. The 1970s were the heyday of the “Toei Manga Festivals,” when the eponymous studio bundled together live-action and anime material for child audiences.

However, some edits stood more on their own, such as 1977’s Space Cruiser Yamato film, compiled from the 1974 TV space opera. The original had done only lukewarm business, but when the film came out, producer Yoshinobu Nishizaki used fans to push it into the mainstream and turn what was meant to be a niche release into a nationwide success. For more, see Chapter 8 of Jonathan Clements’ Anime: A History.

The interplay between film and TV versions was getting complex. A second Yamato film followed in 1978 – unlike its predecessor, it was a new story, a sequel called Farewell to Space Battleship Yamato. As its name suggested, it was ostensibly the end of the Yamato story, with an explosive finale. But not so fast. The film was followed just months later by a new TV series, Space Battleship Yamato II. This was an alternative version of Farewell, using the same premise, but letting characters whom fans had seen die live instead. As such, it was a precursor to the Code Geass films.

A few years later, the Gundam film trilogy came out, which blog readers will know through Anime Limited’s collected home release. Repeating what happened with Yamato, the films were edited from a source TV series which had had poor ratings. Also like Yamato, the films elevated Gundam into an enduring franchise. The films had substantial bits of new animation, along with script changes to draw in fans. They were “Special Editions,” of a kind only just emerging in Hollywood. (Spielberg’s Special Edition of Close Encounters had only opened in 1980.)

By now there were multiple kinds of TV-derived movies. Some were “original” stories using characters also seen on TV. The first Lupin anime movie, Secret of Mamo, debuted in 1978. Two years later, the first kids’ Doraemon film opened, the first of dozens.

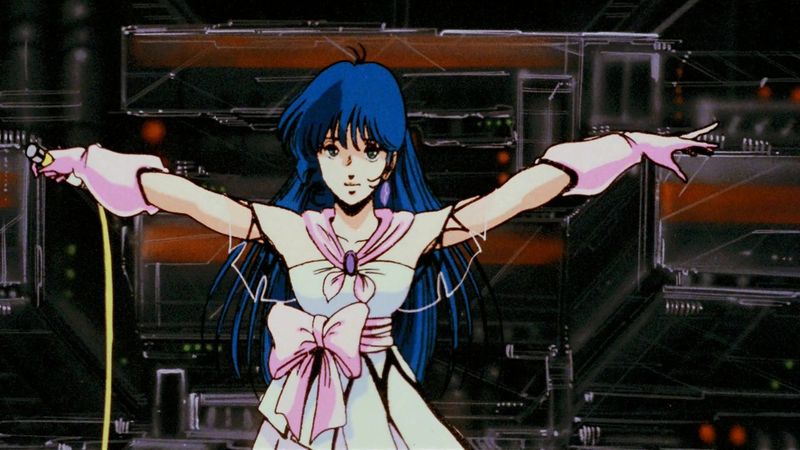

There were also films that retold TV stories with completely new animation. The classic case was Macross: Do You Remember Love? in 1984, which retold the source Macross TV animation with spectacularly better visuals. Most of the Dragon Ball and One Piece films are “new” stories, but some are alternative takes on stories that were already told on TV.

Nowadays, anime fans aren’t surprised by hybrids. Take Tiger & Bunny: The Beginning, the first film based on the Tiger & Bunny TV series. Its first half is a special edition of the opening two TV episodes with extra scenes. The second half is a new canonical adventure, set between the second and third TV episodes. Then there’s Accel World: Infinite Burst, half of which is a TV clip-show before a new adventure starts.

Then there are the first two Puella Magi Madoka Magica films, subtitled Beginnings and Eternal. They comprise a faithful retelling of the source series, with (mostly) the same scenes in the same order, but with gloriously enhanced visuals. Reviewing the films, I commented, “They’re the film equivalents of the ‘ports’ of classic video games like Super Mario Brothers, conversions which leave the play and levels intact and focus on beautifying the graphics.”

And then there are much more meta multi-part adaptations, such as the 21st– century Evangelion films, and the Eureka Seven films from 2017. Both reuse, or seem to reuse, animation from the source TV series, though this can be an illusion. The Evangelion 1.11 film, for example, is based directly on the first six TV episodes, but the animation had to be recreated, and massively revised, from scratch. No cost-cutting here! And both the Eva and Eureka diverge into outrageously different timelines from their sources, using the earlier versions as raw material to remix and sample.

And yet, it’s hardly a sign that everything’s going meta. There are still straightforward edits from popular serials, such as the Attack on Titan films (I wrote up the third here). In recent weeks, anime fans enjoyed another kind of retelling in cinemas, the film Sword Art Online Progressive: Aria of a Starless Night. That revisits the very first storylines in the Sword Art Online franchise, but with all-new animation, a more leisurely pace, and a switch of viewpoint from the hero Kirito to the girl Asuna. Oh, and the film adds a completely new character, although she doesn’t seem out to alter the timeline of the franchise.

Anime TV spinoffs, especially those that retold what we’d already seen on TV, started in a different age. They began before videos, DVD and streaming, before you could binge an old series at a press of a button. They began back when you might watch recycled TV in the cinema just to get out of the rain. And yet they’re still going in Japan.

As of writing, fans of Kunihiko Ikuhara are awaiting Re:cycle of Penguindrum, a two-part film version of his head-spinning ten year-old serial. It’s been billed as a compilation of the series, but with new scenes too.

The “recycle” tag is ready ammunition for critics. Many of these films are impenetrable to outsiders. They can also be shapeless tedium, reducing what might have been excellent source material to story sludge. But at other times they work. Reviewing one “recap” film for NEO magazine, based on a world-famous property, I was surprised to find myself writing that it “streamlines the serial’s rambling last act into a tight, exciting film.”

I’ll end with a comment from my interview with Shoji Kawamori. He was involved not only with changing Macross into Do You Remember Love?, but also with releasing his later drama Macross Plus as a series and movie simultaneously. It was never a TV series – the longer Macross Plus was a video miniseries, made to movie standards already. But Kawamori seemed to relish turning the serial into a movie, rearranging scenes, cutting some and adding more, sometimes changing substantial story points.

“I cannot bear (always) continuing within the same format,” Kawamori told me. “I really enjoy working between them, especially between the first Macross series and the film (Do You Remember Love?) I was able to change all the designs, which I enjoyed very much.” At best, recycling becomes revising; revision becomes a new creation.

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films. The Code Geass movies are being released in the UK by Anime Limited.

[ad_2]