[ad_1]

December 30, 2021

·

0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

The novelist Alexander Key (1904-79) is best known outside anime fandom for Escape to Witch Mountain, the sci-fi story that has thrice been adapted for the screen by Disney. And it’s likely that the release of the Escape to Witch Mountain film in Japan in April 1977 had something to do with the sudden interest of producers at NHK in finding another of Key’s properties to acquire for their big 25th anniversary project, an animated series.

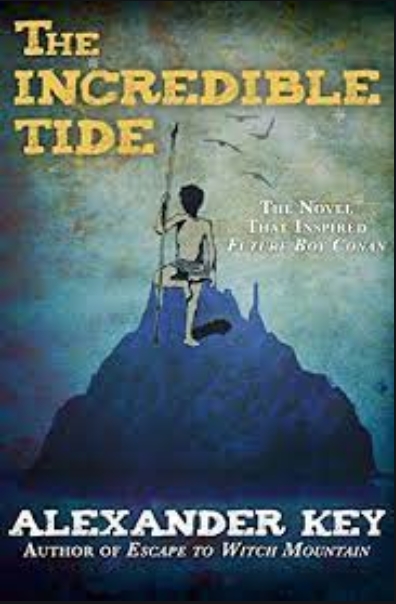

The rest is anime history. Key’s novel The Incredible Tide formed the basis for a 26-part anime, the first (and last) time that a young Hayao Miyazaki would be the show-runner from start to finish on a full-length television series. In the process, Miyazaki veered far away from Key’s original, throwing in a bunch of personal obsessions that would become emblematic of much of his later work in animated features. The finished anime, Future Boy Conan (1978) was a very different beast from Key’s original, and over the decades since, has come to be thought of something that was more Miyazaki than Key.

Out-of-print for many years, Key’s original novel is now available on the Kindle, affording anime fans the chance to re-experience the story as if approaching it as a young Miyazaki in search of raw material. Key’s original begins as a taut, boisterous update of Robinson Crusoe, its protagonist a 17-year-old boy marooned on a deserted island for five years. Asides reveal that Conan had been a child refugee, taken in by a scientist’s family during the early days of a world war between two intractable superpowers that would cause the seas to rise in a global cataclysm. But he has spent his teens entirely alone, after a helicopter crash, giving up on the idea of rescue and hence “rescuing himself,” learning to live on raw fish and seaweed. His sole comfort is the presence of Tikki, a bird that he believes to have been sent by his friend Lanna [sic – not the anime’s Lana] to keep him company in isolation.

A gunboat arrives on Conan’s lonely island, crewed by emissaries of the New Order, a post-apocalyptic group that Conan immediately recognises as survivors from the same superpower that wiped out his family in a war that, even now, is being played down, discussed now simply as “the Change” as if it was a natural disaster. Regardless of how they might have been before the cataclysm (and the text repeatedly hints that they are Soviets), the New Order are now enthusiastic eco-fascists, eking out the very limited resources of the post-flood world – no wood can be spared to smoke fish, and no survivors are suffered to live unless they serve a purpose. But Conan, reasons the New Order’s scheming Doctor Manski [sic, not the anime’s Monsley], clearly has some powerful quality about him if he can survive unaided for five years.

Conan is not the only one – feral children Jimsy and Orlo run in a pack like Peter Pan’s Lost Boys, sometimes pilfering supplies from the enclave of High Harbour. Meanwhile, Lanna’s grandfather, Dr Briac Roa [sic, not the Dr Lao of the anime], now disguised as a criminal called Patch, tries to warn his people that the Change is still ongoing, and that its aftermath will soon cause the tectonic plates beneath their home to snap in a mega-earthquake.

By Miyazaki’s own admission, his outline for the anime only began to wane a third of the way through the story, as he tired of the original’s Cold War-influenced stand-off between two superpowers. Reading Key’s original, it is even possible to spot the moments that might have chafed Miyazaki the wrong way – the back-to-basics setting and the ghosts of ancient conflicts are textbook Miyazaki obsessions, but it’s easy to see how the text might appear infuriatingly blinkered to a Japanese reader, devoted to presenting its Soviet stand-ins as relentless predators, and its America-mirror as good-hearted liberals.

Key ultimately presents both sides as equally deluded and wounded – just as Conan blames Manski’s people for the death of his parents, she blames his people for the death of her son – but such equivocations have a reductive simplicity, a zero-sum game between two equally self-important adversaries, unheeding of the collateral damage their conflict is doing to the rest of the world.

“Don’t you realise it took both sides to do the damage?” one character says, immediately assuming that there are only two sides, and that everybody else just has to live with their fall-out. By chapter two, Lanna’s family in High Harbour are grumbling bitterly about the trade deal imposed upon them by New Order gunships – something that any Japanese reader might more readily associate with the historical actions of the United States, not the Soviet Union.

Nestled within Key’s narrative is a story of adults who have failed the next generation – Dr Roa begged old-time generals not to use his inventions to create magnetic doomsday devices, and is still living with the consequences. He has adopted his Patch nom-de-plume to throw the New Order off his trail, as they mistakenly believe that his scientific knowledge can somehow solve their problems. Conan, like Lanna, like Jimsy and Orlo, is there to save himself, taking charge in the ruins after the heroes of yesteryear have proved wanting. But although Key first uses the term “incredible tide” to describe the upheavals of the great war as if they were in the past, the book offers a precocious warning – that a second “incredible tide” is coming in the form of the predicted mega-quake. Man-made ecological disaster is not a single event, but an ongoing cycle of ever-greater deprivation and compromise, Conan’s generation simply have to live with it, prefiguring the controversial storyline of a much later anime, Makoto Shinkai’s Weathering with You.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Anime: A History. The Incredible Tide, by Alexander Key, is published by Open Road Integrated Media.

[ad_2]