[ad_1]

By Jonathan Clements.

“I’m sure lots of us are struggling right now. But even so, let’s unite our efforts and give it our best shot!” These words are put into the mouth of one of the minor characters of Shinya Kawatsura’s The House of the Lost on the Cape (on tour in the UK this February as part of the Japan Foundation’s annual pop-up festival) but resonate through the years, from a decade in the past, when Japan struggled to recover from a very different crisis.

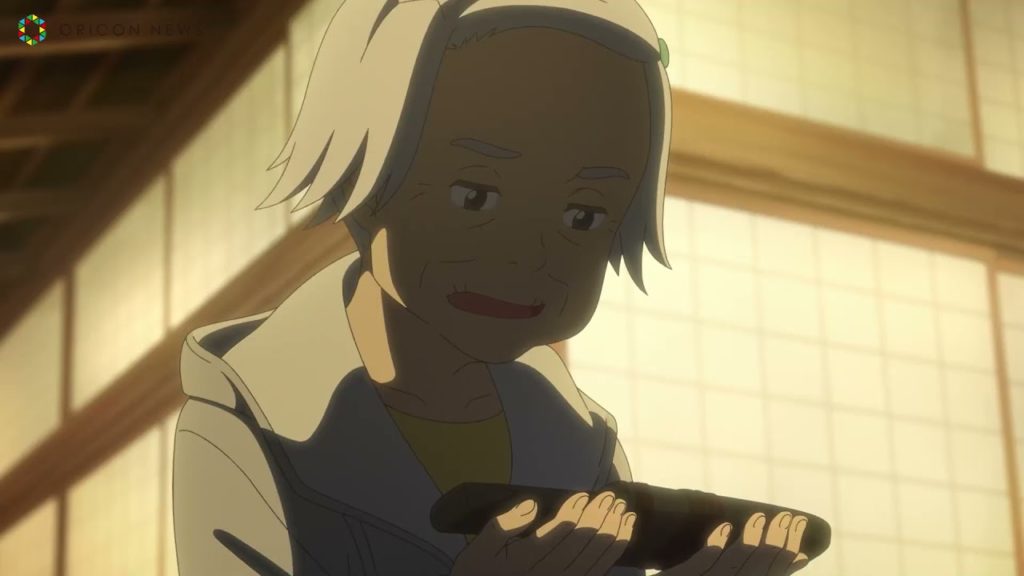

As the disaster relief operation winds down after the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, a grandmother arrives in the town of Kitsunezaki to take care of her homeless relatives. She scoops up the girls Yui and Hyori, and moves them into an abandoned mansion on a nearby ridge, patiently introducing the girls to simple country living.

Except it’s all a fiction. Kiwa (Shinobu Otake) is a total stranger, posing as the girls’ grandmother to keep them out of trouble. Hiyori (Sari Awano) has effectively been orphaned twice, once by a car crash and again by the disaster. Yui (Mana Ashida) is a teenage runaway, who has used the anonymity of Kitsunezaki to reinvent herself as a girl who never has to go back to school again. And there are other tall tales, too, as Kiwa starts to regale her surrogate family with folktales from the rich traditions of nearby Tono…

House of the Lost was one of many fictional responses to Japan’s 2011 earthquake and tsunami – other examples that spring to mind include Makoto Shinkai’s Your Name, and the stories collected in March was Made of Yarn. Written by the local novelist Sachiko Kashiwaba, known already to anime fans as the originator of Birthday Wonderland, and serialised in northern Japan’s Iwate Nippo newspaper, the House of the Lost novel subsequently won the 2016 Noma Prize. Kashiwaba is a writer with a long publication list of children’s fantasy and explorations of Japanese folklore, and has recently received the prestigious Batchelder award for books originally published in a non-English language for her Temple Alley Summer. With her Iwate tales, Kashiwaba was simply writing what she knew, only to be caught up a decade later in a government-funded initiative to funnel funds into the region where her stories took place.

Kashiwaba, who excels at telling tales about the places that connect the everyday with the paranormal, presents the Tohoku disaster as a sudden, brief portal opening between worlds. It brings the people of Kitsunezaki (Fox Cape) back into contact with their roots, reminding them of the long, long cycles of deep time – there, for example, is a cataclysmic earthquake and tidal wave in north Japan roughly once every 1100 years. But Kashiwaba also exploited the disaster’s effect on far more prosaic elements of people’s lives – causing people to move house, change schools, and in some cases, walk away from unwelcome elements of their old lives.

Kiwa remains politely vague about how she is so connected to the spirit world, waving off Yui’s queries as to whether she is a witch or a sorceress. She claims merely to be a harmless old lady who happens to be able to communicate with “enigmas”, but there are tell-tale signs that she is more than that, starting with the comma-shaped hairpin she has, reminiscent of ancient, sacred magic stones. Reiko Yoshida’s script playfully teases the audience, flirting for a moment with the notion that Kiwa is not a kindly old lady, but a sinister serial killer, just about to murder the girls with a pair of garden sickles.

When Yui first tries a mouthful of Kiwa’s cooking, there is a tense pause… as if she is wondering if it is poisoned. The anime even flags this caution with a knowing reference, as Hiyori unpacks her meagre possessions and places a copy of Hansel & Gretel on her desk.

Yui retells the story of Hansel & Gretel, but the staging is flat and uninspiring, because this is not the sort of fairy story that the film is really interested in. It’s saving itself (and its budget) for the local traditions, as Kiwa launches into one of the region’s folktales, and the mundane world we’ve seen so far is suddenly transformed into lush, scrappy motion-capture. Kiwa retells number #63 from the Tales of Tono, about an old woman who stumbles across a magic mansion (a mayoiga), takes nothing from it, and is rewarded later on by finding a rice bowl that never runs out.

The folklorist Kunio Yanagita, inspired by the work of the Brothers Grimm, published his Tales of Tono in 1910. It was by no means his only work in that mode (I treasure his exhaustive 1943 account of legends of the Shimabara region, for example), but it was the first book of its kind in Japan, and put the obscure district of Tono way ahead of the competition in terms of anthropological tall tales. Even though Yanagita himself would uncover multiple variants all over Japan, the fact that Tales of Tono got there first has often led to the assumption that certain legends originated there. Most enduringly, Tono has become a famous tourist destination for people tracking the five stories concerning kappa water-sprites that Yanagita uncovered there, as seen even in other anime, like Keiichi Hara’s Summer Days with Coo.

In the Tales of Tono, a mayoiga is a very specific kind of place: a magic house that offers sanctuary to those who have lost their way. The way the stories are framed implies that a mayoiga appears to the pure of heart, people who have had bad luck in their lives and deserve a break, offering a roof over their heads, and the right to take whatever they want from the supplies inside. The implication is that they can be trusted not to ransack it – several of Yanagita’s collected stories allude to greedy villagers who go looking for some hero’s mayoiga, only to find that it has already disappeared.

Inevitably, House of the Lost recalls many a supernatural anime that rests on the folklore of particular parts of Japan – such as Hiroyuki Okiura’s A Letter to Momo, which featured a menagerie of folk creatures from the legends of the Inland Sea, or Isao Takahata’s celebration of the Tama Hills tanuki in Pom Poko. But I was also reminded of Naoko Ogigami’s live-action Seagull Diner (2006), which similarly follows three Japanese women as they make a gentle and discreet escape from lives that do not suit them. Ogigami’s story does not even reveal what it is that two of her characters are running away from, an idea that is also adopted here, with no real discussion of Kiwa’s background. In Kashiwaba’s original novel, she is revealed as a woman who is just as much on the run as the girls – freed from her former life by the earthquake, which conveniently strikes on the eve of her move into a forbidding old people’s home. Instead, she seizes the chance to live her life once more, snatching up the girls as a surrogate family. But ever in search of balance, and in consultation with the author, Kawatsura deliberately made Kiwa a more mysterious figure for the film.

Halfway through, the ladies adopt a rescue cat, but in a sense, they are all “rescues” of one kind or another. Kiwa names the cat Kofuku, or “little fortune”. Our fortune doesn’t have to be grand, she says, we just have to find small moments of happiness here every day.

Reiko Yoshida’s script continually returns to the Millennial, urban Yui’s surprise at how easily she takes to rural living. She turns up her nose at the basic sleeping arrangements, but then admits that she hasn’t had such a good night’s sleep in years. Before long, she is taking the appearance of supernatural creatures in her stride, and cheerily asking Kiwa if she will teach her the recipe for home-made soap. Director Kawatsura’s favourite scene in his own film is one of Yui’s revelations, when she sits down to eat what she first regards as a bowl of grass and weeds from the garden. But there is more to her delight at how it tastes than a simple celebration of organic cuisine. Instead, Kawatsura balances it with a flashback in which we see how awful mealtimes were in the household of Yui’s bitter, widowed father. “I thought to myself,” says Kawatsura, “that in a home like that, with all that tension, food just wouldn’t taste good. What Yui is tasting for the first time at the mansion isn’t just the food, it’s loving company of a stranger who cooks her a meal.”

The voice of Kiwa is provided by Shinobu Otake, already on anime fans’ radar after her performance as the title character in the acclaimed Fortune Favours Lady Nikuko. That, too, was a story of an unlikely family, making do in a coastal town on Japan’s north-east. If that seems like an odd coincidence, it’s probably worth bringing up the fact that the year of both films’ production, 2021, was the tenth anniversary of the Tohoku Earthquake, leading to the greenlighting of several productions related to it. In the case of The House of the Lost on the Cape, it was officially commissioned as part of Fuji TV’s Zutto Ouen Project 2011+10, an initiative designed to tell stories set in the three prefectures of Iwate, Miyagi and Fukushima, in turn intended to incentivised tourism in the areas most drastically affected by the earthquake and tsunami. However, director Kawatsura denies this, telling me instead that the film was already in production at the time the Zutto Ouen scheme was announced, and that being co-opted into it was a happy coincidence.

The film’s early sequences, in which a multi-generational trio explore an ancient country house, recall the set-up for Hayao Miyazaki’s My Neighbour Totoro. It even repeats some set-ups shot-for-shot, as the girls get the old pump working, and start mopping the floors. After slow beginnings, in which long pauses stretch into almost Pinteresque silences, even the animators tire of the real-time approach to cleaning, and start speeding up the housework with jump-cuts. But if that all looks generic, it was part of the joy that Miyazaki took in the set-ups originally – that life in the Japanese countryside had been unchanged for multiple generations before the 1950s. Totoro took joy in what, for Miyazaki, had been the everyday nature of country life. In the 2020s, The House of the Lost on the Cape revisits the same situations as glimpses of a world that has all but gone, but one into which a national crisis has forced some people to return.

The everyday world starts to seep back in. The local kids go back to school, except Yui, whose new identity has allowed her to bunk off indefinitely. The implication that her “grandmother” is now taking care of her is even enough to throw a suspicious teacher off the scent, but instead Yui must somehow survive in the adult world. Devoid of qualifications, and with questions yet to be asked about her false identity, she takes a job at the local supermarket. This, too, is a fantasy world, a brief, dreamlike return to the non-digital realm of a generation before. Yui’s newfound adventures can only possibly last as long as the Japanese infrastructure is too damaged to ask her what her bank account number is.

Meanwhile, Hiyori finds new acceptance in a local performance troupe, which is rehearsing a fox-dance as part of a local carnival. This, again, is a mundane activity that somehow connects the characters to Japan’s past and folklore. Talk of the “summer festival being cancelled, but we hope there will be an autumn one” feels oh-so-2022 in its acceptance of disruptions and recovery.

Hiyori is triggered by the sound of a folk song, which makes her remember the sorrows of her parents’ funeral, but much of the scene is played out in a locked-off long shot, her pain and anguish only visible in her body-language as we watch from a distance, the soundtrack still incongruously dominated by a joyful song about sailors returning to port. It is an intriguing balancing act of sound, vision and action, and the sort of thing on which the director, Shinya Kawatsura, evidently prides himself.

Kawatsura came up through television, working as a director and storyboarder on Sagrada Reset and Magic of Stella before going into films with Non Non Biyori and A Certain Magical Index: The Miracle of Endymion. He also has a long track record in storyboarding, and is usually the responsible party for much onscreen imagery not in the original script. One opening shot lingers on the image of nature’s resilience, as demonstrated by the simple, everyday sight of weeds forcing themselves through cracks in the pavement. But this is a film in which supposedly intangible, unseen objects exert a physical presence in the real world, even including the “camera” of the animators, which audibly rustles through the rooftop flowers as it executes a 3D crane shot of the titular house on the cape. When I mention to the director that I feel the shot encapsulates the entire film, he admits that he likes to do something similar in all his work. They’re like overtures, he beams, “a moment that says what is going to happen.”

Kiwa’s second story interlude, about the origins of the Kitsunezaki fox-dance, does not appear in the original Tales of Tono – it is only part of the folklore of Iwate in the sense that it was invented by Kashiwaba the novelist. When she finishes, her audience sit in rapt silence, realising that the Cape of the Fox Cub, where their house is located, is the site of a legendary battle between human villagers and snake monsters from the sea. But Kiwa has realised that the tsunami also destroyed an off-shore shrine, which she suspects was the lock holding shut an ancient underwater prison, in one of the “kiln” caves beneath the local cliffs.

To deal with this disruption to the paranormal infrastructure, she will need supernatural help, drafting in the assistance of a bunch of bickering kappa sprites, voiced by the comedy duo “Sandwichman”, the actor Shohei Uno, and, in something of a coup as the beanpole of the group, Takuya Tasso, the flamboyant and media-savvy governor of Iwate Prefecture. Although since he only has a couple of lines, one of which is “Hm,” he could have literally phoned them in.

Ultimately, of course, it’s Tono to where the characters travel, for a conference of all the spirits and enigmas from the Tohoku region. There, they slyly allude to the possibility that the Tohoku crisis in 2011 was merely the first harbinger of a whole run of global bad luck, about to descend on the human race. If Tohoku is the place where it all started, they reason, then Tohoku is the place that can shore up the good fortune of the rest of the planet. It’s a lovely idea, and suggests that Brexit, Donald Trump, the California wildfires and COVID-19 might all be easily solved if some water spirits and their magic mates can seal up a cave somewhere in north Japan.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Anime: A History. The House of the Lost on the Cape is screening in selected UK cinemas in February and March as part of the Japan Foundation Touring Film Programme.

[ad_2]