[ad_1]

By Andrew Osmond.

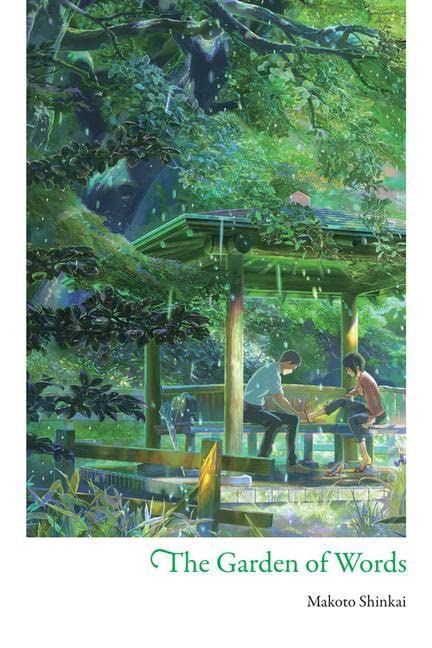

This August, Makoto Shinkai’s film The Garden of Words – soon to have a new Blu-ray/CD Steelbook – will be adapted as a London stage play. It runs at the Park Theatre at Finsbury Park from 10th August 10 to 9th September; if you want to know more, I interviewed director Alexandra Rutter on this blog about developing it. That was in 2020, when the play was meant to come out – you can guess why it was delayed.

As Rutter mentioned to me, and has confirmed in more recent interviews, the play isn’t just based on the Garden of Words anime. It also draws inspiration from the book that Shinkai adapted from his own film, which is available in translation from Yen Press. A caution: I’ve linked to the page for the Kindle edition, which I bought myself. Amazon seems to have physical copies of the book too, though the “reading sample” on their page links to the manga of Garden of Words, which is apparently out of print.

It’s not surprising the play will draw on Shinkai’s novelisation, as it’s a really good book. It also stretches the definition of novelisation. The film’s story is retold in it, and it’s still the emotional centre… but most of the book consists of all-new material, scenes and subplots going past anything on screen. Shinkai treats the anime as a short story that he widens into a novel, and very successfully too.

As you’d expect, the lead couple, Takao (the schoolboy) and Yukino (the woman) are both filled out; their lives, relationships and backstories, Yukino’s past especially. But Shinkai surrounds them with portraits of four more characters, who were only glimpsed in the film. They’re each given a lengthy chapter from their own perspective, whose intersections with the “main” story are less important than the parallels, the rhymes that Shinkai sets up.

These new profiles start with Shouta, Takao’s older brother, who’s already operating in the adult world (he’s glimpsed moving out of the family house in the film). Then there’s Mr. Itou, who was Yukino’s former teaching colleague and romantic ex – they talked on the phone in the anime, when Yukino’s career was already in ruins. We learn far more about the girl behind that ruin, Aizawa, whom Takao confronted in the film’s one violent scene. Last, we meet Takao’s mother, who had mere seconds of screentime in the anime.

These portraits impressed me more than the book’s handling of the “main” plotline, for reasons I’ll explain later. The chapter on the ostensibly villainous Aizawa stands out especially. I couldn’t be a worse demographic to judge a portrayal of a teenage Tokyo girl… but it seemed horribly convincing to me, way outside anime stereotypes, and far beyond Shinkai’s anime. From early in Aizawa’s story:

In a world overflowing with awful, disgusting boys, the rampant obsession with romance among middle and high schoolers was exhausting. Actually, it was even worse than that; lately people seemed to take it for granted that even elementary schoolers would be in love. Magazines meant for grade schoolers ran articles like ‘Hugely popular with today’s little fashionistas! Hot clothes that will make you look slim and curvaceous, even if you have a teddy bear figure!’As a grade schooler, it all made me so bitter and angry and hopeless.”

From there, Shinkai takes us through Aizawa’s turbulent adolescence, full of fateful turns, swings in attitude, interludes of joy… and then down, through Aizawa’s perversely determined passivity as an adoring girlfriend, and then to a ghastly choice she makes in bitter defeat. It’s full of caustic power Shinkai generates huge sympathy for the character without insisting on any kind of judgment – that’s left open for the reader to make, or not. “Pain prickled my skin,” Aizawa reflects, “and the only word I had for that feeling was happiness.”

It’s no surprise that Shinkai can write a convincing teen. But his chapter on Reimi, Takao’s mother, is perhaps as good. It involves deep pathos, but also some delightful humour that reminded me of the mum in The Case of Hana and Alice. In a delicious scene, Reimi amusedly quizzes Takao about his mystery girlfriend, reflecting “Male virgins are so cute when you tease them (and I’m pretty sure he is one).” If Shinkai had put that line into the film version, think how different it would have felt… but we’re just getting started.

Of the male ascended extras, I prefer Mr. Itou, Yukino’s former boyfriend, a perfectly ordinary guy who cultivates a thug image to the students he teaches. (Anyone with teaching experience will understand why.) And yet, his chapter is a tender story of regret; as he did with Aizawa, Shinkai encourages our empathy without forcing our judgement one way or another. Some of the complications arise from Yukino and Itou having to keep their relationship private, though it’s not remotely illicit, unlike the potential relationship at the heart of the book. “It was like a hopeless middle-school first love,” Itou reflects in an on-the-nose line that Shinkai just about gets away with. “No, it was worse.”

Takao’s big brother Shouta gets a comparatively ordinary story, of an adult relationship with tensions and issues, but one that’s far from hopeless. Coming early in the book, some readers may find it pointless in its lack of a big payoff – actually, there is a payoff, but it comes much later, after we’ve met everyone else. The story is more satisfying in retrospect, arguing quietly between practical and idealised perspectives, and grounded in the grind of Shouta’s office job. In his afterword, Shinkai mentions he talked to poetry professors, shoemakers and students, but also to people working in sales for manufacturing companies – this chapter is why.

In the same afterword, Shinkai identifies Garden’s linking theme as “lonely sorrow.” In the seventh-century poetry quoted through the book, those are the Japanese characters that comprise the word “love.” The theme will hardly come as a surprise to Shinkai fans. But the book, like the Garden film, wallows less in forlornness than his earlier anime. There are no long interludes in an empty snowbound train carriage, or in an even emptier dreamworld – though Takao dreams of being a crow in one of the book’s hokier scenes.

Takao and Yukino are distinguished by a simple device. While their chapters take their intimate viewpoints, they’re written in the third person, while Aizawa, Reimi, Itou and Shouta have first-person narrations. Shinkai lets this distinction slide in a key scene, which works fine, though I hardly found it “experimental” and “dizzying” like Noriko Kanda, whose guest review ends the book. In the story, none of the supporting characters know about Takao’s and Yukino’s friendship. However, the teacher Itou knows them both separately (he bawls out Takao over his low school attendance), and he finds himself comparing them:

“You wouldn’t instantly pick them out of a crowd, necessarily. They have friends, and they laugh, and they don’t make waves. If you look closely, though, you can tell. When you see hundreds of kids a year, you learn to spot these types. Both Yukari and [Takao] Akizuki secretly have something in their hearts that’s special to them, that they’d never hand over to somebody else. It may be something strangers would value, or it could be totally worthless. I can’t tell, and it doesn’t matter. But that divide between them and everything around them is undeniable and unbreachable.”

It’s stressed that Yukino is extraordinarily attractive – something not obvious in the anime medium, where “beautiful” is the female default. She’s an object of desire from both male and female characters. At one point Itou, ashamed of himself, secretly likens her to sex dolls, “beautiful vessels, stripped of their wills.” Viewers of Perfect Blue may wonder if Yukino stands in the same relationship to her schoolgirl nemesis Aizawa as Kon’s heroine Mima did to her frilly-frocked phantom double. Is Yukino a repressed female, whose unvoiced fury is embodied in her adversary?

Shinkai doesn’t push that reading, but he does show both Aizawa and Yukino engaging in practically identical behaviour when they’re young and vulnerable and encounter adults who seem magical to them. In both cases, the adults are teachers, which ties in with Takao’s story too, even if Takao doesn’t know Yukino’s a (lapsed) teacher. “Everybody has their quirks,” says a character early on, and in Shinkai’s book it’s not just men who objectify others in guilty ways. Here’s Yukino observing a dozing Takao:

“He was resting his head against a pillar, and his thin, boyish chest rose and fell in an even rhythm. She realised, for the first time, how long his lashes were. His youthful skin seemed to glow from the inside; his clean lips were slightly parted, and his defenceless ears were as smooth as a newborn’s… He really is young, huh… She was oddly happy that it was just the two of them in this small arbor in the Japanese garden; she could observe him openly as much as she wanted.”

For some lovers of the film, this may be Too Much Information, given that yes, Takao is fifteen years old and Yukino is twenty-seven. There’s far more female gaze in the book – notably, the central sequence where Takao measures Yukino’s foot is from her viewpoint as well. (As she offers her foot to the boy, Yukino finds herself thinking of a wagtail, “the bird that taught the gods about carnal knowledge between men and women”). The potential for transgression was in the original anime, of course. But the book removes much of the film’s careful ambiguity – suggesting that for Shinkai, you can do nearly anything in anime, but go that little bit further in print.

Whether that bit crosses a crucial line, turning a wholesome anime character study into barely sublimated shotacon, is a question for another article. Certainly Shinkai is interested in characters being disrupted by their own feelings. There are two separate scenes where Takao or Yukino are in intimate situations, only to have stray associations cross their minds and undo everything. In Takao’s case, it’s a thought he has about his mother, and readers may finish this book quite certain that mummy is what makes Takao tick. “Even to her son, she looked very young,” Shinkai specifies. For the record, Shinkai said in an interview that “the theme of the anime isn’t how to overcome a mother complex… It’s just one element of Takao’s character.” The book, though, leaves other readings of Takao open, even as they close Yukino down.

My own reservation with the book is with how the central meetings between Takao and Yukino often read very awkwardly, far less assured than the sumptuous atmospherics on screen. There’s an obvious difference with those atmospherics – Shinkai refers to the rain umpteen times in print, but I never felt it as I did in the film. Then there are instances of Too Much Information, where an initially strong description gets ruined by explanation. An example:

“The wisteria trellises in the Japanese garden have bloomed… In the abundant rain, the vivid purple seems to glow. The round, lustrous drops are unbearably sweet as they build and build in the flowers until they spill free in an unbroken stream. It’s as if the wisteria flowers had hearts, brimming over with impressible joy.”

You might argue that this is from a “Takao” chapter and reflects the character’s boyish naivete, but it clangs all the same. In his afterword, Shinkai argues mischievously that visuals “are an inevitably superior, and more fitting, means of expression” than writing. You can take that as Shinkai’s gentle trolling, but he certainly seems better suited to presenting luminous moments and settings on screen than he does in print.

That said, the book’s version of the foot-measuring scene through Yukino’s eyes does rival the anime, perhaps that’s because Shinkai enjoyed reconfiguring it so much. However, even that’s marred by some wincingly hokey sentences, which are far more annoying to find in a book which is so much better than them.

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films. The book of Garden of Words is published by Yen Press.

[ad_2]