[ad_1]

October 23, 2023

·

0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

Warner Brothers’ acquaintance with anime has twin foundations: a yellow rodent and a red pill. Warner Brothers’ handling of Pokémon and The Animatrix reflect the opposite ways that Western distributors sold anime abroad in the early twenty-first century: either conceal its Japanese origins, or else make them a selling point.

Pokémon was marketed as a straight kids show, and did massive business on those terms. Released in America in 1999, Pokémon: The First Movie earned more than $85 million in Stateside cinema. (For comparison, Spirited Away scraped barely $10 million in US cinemas a few years later.) Most of Pokémon’s preteen audience couldn’t care less about its Japanese origins, making the franchise comparable to “hidden imports” and for-hire work. It certainly didn’t prompt an interest in anime as such. As Norman J. Grossfeld, the Warner 4Kids president who helped adapt the Pokémon film, said in 1999, “Right now, Pokémon‘s success has companies rushing to Japan to look for programs like Pokémon. Not for anime in general.”

The Matrix, though,was something else.

In press interviews, the Wachowski siblings stressed The Matrix’s debts to anime – especially to Akira, Ninja Scroll and the first Ghost in the Shell. (Carrie Ann-Moss’ heroine Trinity could have been Kusanagi’s scowly sister.) The DVD edition of Animatrix included an excellent documentary, ‘From Scrolls to Screen,” which suggests that common anime practices – low frame counts compared to US animation, more emphasis on atmospherics than on ‘acting’ – led to anime which looks really cool to foreigners. We’re talking about stylised, sometimes frozen action poses; the pregnant pauses before someone’s body explodes; the slow pans over moody backgrounds; and so forth.

It’s the kind of unreal reality that The Matrix went about recreating in live-action (plus lashings of CGI). You can argue about if what it captured was really the “anime style,” but it was massively important in promoting anime to the world. Even to the Japanese. Interviewed on “From Scrolls to Screen,” Future Redline director Takeshi Koike said, “Of course, when you are shown this sort of thing (The Matrix), your desire to create images which can’t be topped gushes forth, so on that level The Matrix was an influential work.”

That was a boost for anime in itself, but the Wachowskis went further by overseeing The Animatrix. This was an animated DVD anthology, mostly animated by Japanese film-makers including Takeshi Koike along with Yoshiaki Kawajiri (Ninja Scroll) and Shinichiro Watanabe (Cowboy Bebop). Other talents in Animatrix’s credits included maverick character animator Shinya Ohira, whose impressionistic skateboarding defines the “Kid’s Story” segment by Watanabe, and Mahiro Maeda, who directed Blue Submarine No. 6 and co-directed Evangelion 3.0.

Takeshi Koike directed a segment called “World Record,” where a champion athlete races so fast he breaks free of the Matrix. “I was very careful to show the movements of the (runner’s) muscles in a subtly deformed style,” said Koike. “I studied a lot of running in slow motion; I found that making the hands, rather than the legs, swing up with a very strong impact, makes the animation quite realistic… I make (my characters) somewhat deformed. But if the designs get too exaggerated, the animation itself breaks down. So I wanted my characters to still have a realistic feel.”

Mahiro Maeda co-directed one of the anthology’s best segments, the two-part “Second Renaissance.” It’s a bravura depiction of The Matrix’s end-of-the-world backstory, showing humans conquered by the machines they abused. The revolt of the robots story is dazzlingly-illustrated pulp, but put on another level by its resolutely doom-laden tone. Its fusion of religious-apocalyptic imagery and grim, contemporary references (Vietnam, Tiananmen Square) is comparable to the live-action film Children of Men.

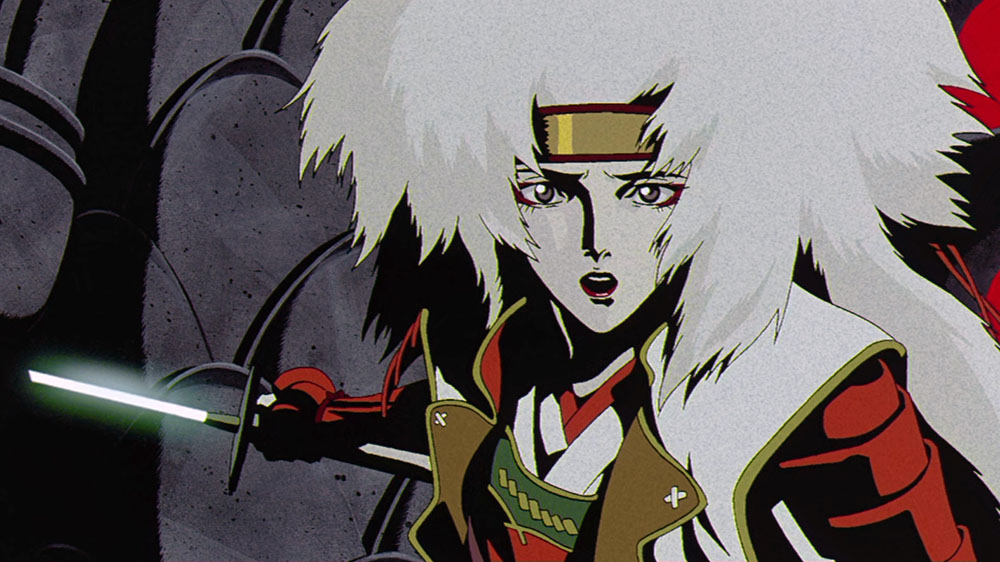

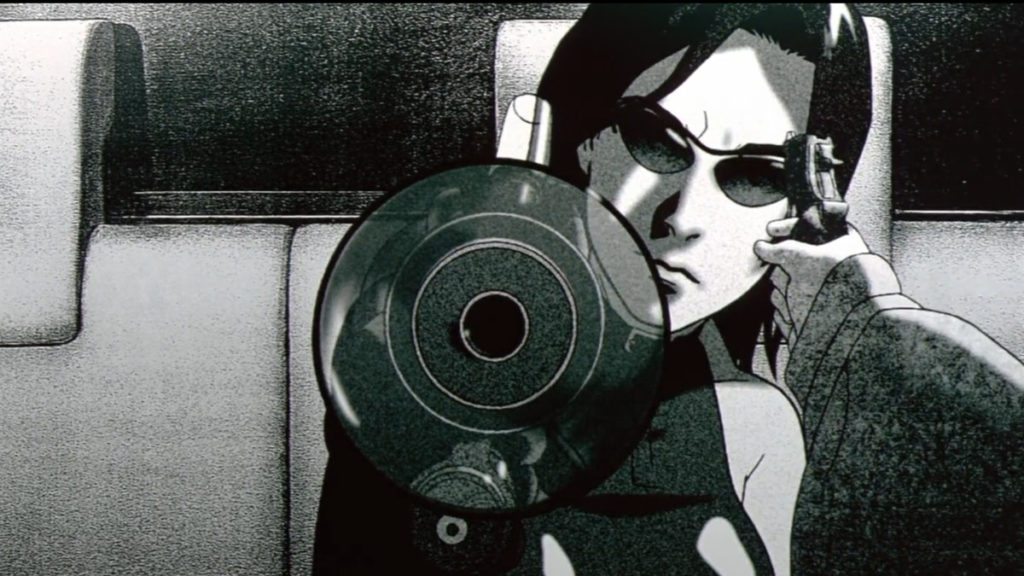

The other Animatrix episodes include Watanabe’s “A Detective Story,” a witty SF noir with beautifully-shaded monochrome city backgrounds; and Kawajiri’s samurai story “Program,” a vividly dynamic action piece mixing flat painterly designs (the simplified colours are stunning) with stylised, multi-planed 3D sets.

But the “From Scroll to Screen” documentary on the DVD was arguably was arguably just as important as an advert for what manga and anime are, where clips from Ninja Scroll rubbed shoulders with Space Battleship Yamato and Grave of the Fireflies. It remains a brilliant anime primer for Matrix fans curious about where Neo and co came from… and thanks to the Matrix connection, The Animatrix sold in the hundreds of thousands of copies worldwide.

Animatrix is screening at this year’s Scotland Loves Anime.

[ad_2]