[ad_1]

By Andrew Osmond.

Makoto Shinkai has made anime since the 1990s, but his three latest features – Your Name, Weathering with You and now Suzume – form their own little sequence. Thematically, they’re about natural disasters. Tonally, they have a crowd-pleasing blend of spectacle, heartbreak and humour. Their comedy especially marks them off from Shinkai’s previous anime (try finding a funny bit in Garden of Words or 5 Centimeters). Commercially, they’re domestic blockbusters, inside the ten top-grossing Japanese films in Japan as of writing. Many viewers will think of them as Shinkai’s “defining” films, with everything he made before an apprenticeship.

However, these three films are also exceptionally deft in handling their respective lead characters, and subverting our expectations. In what follows, I’m presuming readers have seen Your Name and Weathering, so there’ll be SPOILERS for both. For Suzume, the spoilers will be far smaller, though some readers may prefer to skip the last paragraphs.

Long before Your Name, Shinkai was foregrounding boys, girls and their yearnings for each other. That’s an obvious engine for a story, as it is in non-Shinkai anime ranging from Miyazaki’s Laputa, one of Shinkai’s favourites, to Satoshi Kon’s Millennium Actress, whose killer last line has viewers arguing if it’s a romance at all.

In Shinkai’s early films, sometimes he foregrounds the girl’s perspective, sometimes the boy’s, and sometimes he makes them into a duet. In Garden of Words, which Shinkai made directly before Your Name, he frames the film’s first half entirely through the eyes of a naïve schoolboy, Takao. We’re shown how he sees the beautiful, elegant woman in Shinjuku-gyoen park, as an exquisite mystery. “To me, she represents nothing less than the very secrets of the world,” he says. It’s only well into Garden that we’re privy to the woman’s viewpoint, though some information is still withheld till Takao discovers it.

Garden of Words isn’t a “twist” story; it just discloses information in a canny way. Shinkai’s twist film is his next one, Your Name. I’m presuming readers know the story, so I won’t summarise it in detail. But if you’ve not seen in in a while – it opened in Britain seven years ago – then have another look at how the story works.

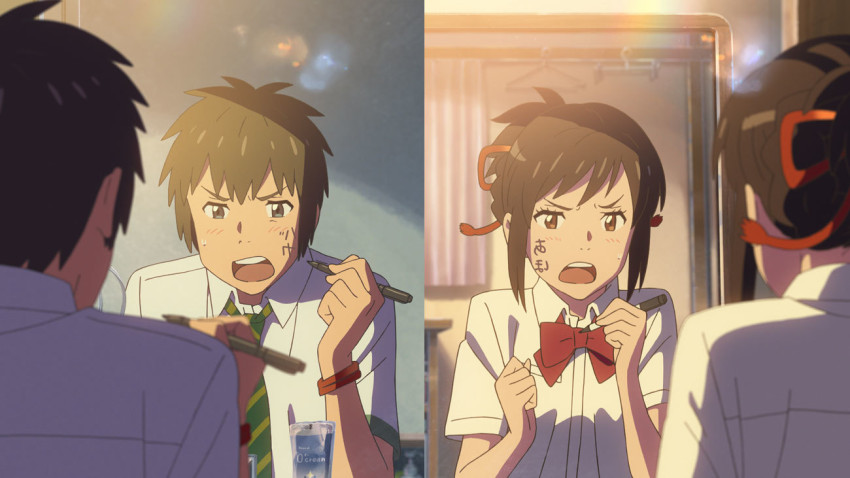

The first quarter-hour takes the viewpoint of the girl, Mitsuha, establishing her life in the mountain town of Itomori. Then we continue to follow her in Tokyo, only now she’s in the body of someone else, the boy Taki. Of course, this makes for a most unusual viewing experience. Our protagonist now looks and sounds entirely different, so we have to remind ourselves “she’s” the same person.

It’s nearly half an hour before we’re introduced to the real, very confused Taki, who’s sometimes in his own body, sometimes in Mitsuha’s. The film enters its duet phase, showing the youngsters and their overlapping lives, while both they and the audience remain discombobulated. For example, there’s a scene where Taki-as-Mitsuha accompanies the girl’s family up a mountain to a shrine. The script makes clear it’s “really” Taki, but now he’s swapped entirely into Mitsuha’s life and family that was established in earlier scenes.

Then, suddenly, Mitsuha vanishes from the story, as Taki stops swapping into her life. The next part of the film is Taki’s search, as he tries to work out where Mitsuha’s town is. And then… he and we learn that Mitsuha, her friends and family, were all dead along, killed by a falling comet three years ago.

It’s a beautifully built twist, reinvigorating a hoary story sting (“He was a ghost all along!”). And a key reason it works so well is because Mitsuha’s perspective is central to the early scenes; it’s so much her story. Your Name is less The Sixth Sense than Psycho. It takes the time and effort to set up an engaging protagonist, then kills her off with more than half the story to go.

Of course, Mitsuha isn’t irrevocably dead, and the audience is soon invested in Taki’s efforts to save her, as Shinkai continues playing with the blurring of viewpoints. There’s a flashback where Taki sees intimate details of Mitsuha’s life, including her birth. Later, as he Taki cycles desperately up the mountain in Mitsuha’s body, Mitsuha’s memories “leak” into his mind, so he relives their first meeting (in Tokyo) from Mitsuha’s point of view.

That bit’s confusing on first watch, a fault of the film. But it also prompted some viewers to watch it again, and it’s on rewatching that Your Name’s elegance becomes truly clear. It’s like classic crime films, which routinely show identities blurring and transferring, criss-crossing. In the first moments of his 1951 film Strangers on a Train, Alfred Hitchcock symbolised the idea with an image Shinkai would love – converging train tracks.

This motif is so strong that many of Your Name’s “problems” matter little. You could complain, for example, that Taki and Mitsuha fall in love shockingly fast. But when we see them living each other’s lives, is that so unreasonable? The film’s also lopsided in that we see little of Taki living as Mitsuha, but that’s why the twist has such force – at that point, we identify as Mitsuha. For the record, Taki’s side of the swap would be filled out in a spin-off book, Your Name: Another Side (review).

Weathering with You, Shinkai’s next film, has no such ostentatious twists. However, the way it handles the lead characters has Your Name’s cunning. A great deal of the film is framed from the viewpoint of the boy character, Hodaka; and yet Shinkai constructs the story to give the girl, Hina, an independent reality. Notably, the very first scene shows Hina, not Hodaka (it’s when she’s at the hospital with her dying mother and is summoned to the world above). True, Hodaka’s voiceover is present, but he’s telling us her story, not his.

You could label what ensues as a “boy saves girl” tale, except there are so many details that subvert that. Consider the early scene where Hodaka recklessly uses a (real) gun to save Hina from a sleazy yakuza type. The scene references the male teen fantasies in Catcher in the Rye,the book Hodaka carries. As I wrote in a review for NEO magazine, “Hodaka escapes with Hina, and she chews him out for his recklessness. Instead of blustering defensively, Hodaka collapses like a limp rag before her. This kid wants to act tough, but he has no true machismo. Even at his angriest or most desperate, what plainly drives him is fear.”

This power relationship continues in what happens next. “Hina takes pity on the boy, and reveals her magic – the ability to part the clouds above and let down rays of sunshine, just by praying. Hodaka accepts her power immediately, in another of Shinkai’s reflections on what adolescents see as magic. For Hodaka, it’s amazing to see a pretty girl command the weather; but what’s really amazing for a teen boy is that the girl tolerates him and enjoys his company.”

This is also where Shinkai sets up a little story trick. Hina claims in this scene that she’s slightly older than Hodaka; in other words, she’s his senior. That’s assumed for much of what follows, only for the lie to be exposed at a crucial moment, drawing attention to the power of assumed narratives. Granted, the point when Hodaka realises he was the older partner is also the moment when Hodaka resolves that he can save Hina, he must save Hina. Ultimately he does; but this turning point only comes after Hina has been comprehensively shown to be smarter, stronger and braver than him, and he can’t even use their age difference as an excuse!

In Suzume, the film’s biggest twist regarding its main characters is given away in the trailers, though if you want to stay unspoiled, stop reading. Early in the film, the titular schoolgirl, living on the coast of Kyushu, sees a smoulderingly handsome youth. This stranger is named Sota, and he has about ten times the maturity of Hodaka and Taki combined. In a spectacular set-piece, Suzume helps Sota close a magic door to lock away dangerous, wild magic.

And then… Sota gets turned into an ambulatory chair and that’s pretty much how he stays. I won’t give away if Sota is turned back again, but it’s a wildly funny subversion of “boy meets girl.” It’s even sweeter if you remember how disappointing such gambits can be in animation. In 2009, Disney introduced its first ever animated African-American heroine, Tiana, in The Princess and the Frog, only to turn her into a frog for most of the film. Sota, on the other hand, ends up with far more pathos and power in chair form than he could ever have had as a bishonen. To put it another way, Sota is far less wooden as a chair.

But Suzume goes further than that. Suzume and Sota are admirably loyal and committed to each other, but the girl-meets-boy, girl-meets-chair thing is a false front anyway. The important relationships in Suzume are all female, in a film that’s told almost entirely from female perspectives. I said at the outset that Suzume feels like it continues the sequence of films that began with Your Name and Weathering. But it might also be starting the next phase of films by Makoto Shinkai.

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films.

[ad_2]