[ad_1]

June 16, 2023

·

0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

“I have loved novels, films and animation since I was a child,” says scriptwriter Reiko Yoshida, “and I was hugely interested in the world of stories. But it was not until I graduated from university when I thought I would make a career out of it.”

However, she wasted no time after that, swiftly penning the script that would become her calling card in 1991, Let’s Go to B-Club Paradise. It was the tale of an ordinary housewife, caught shoplifting and recruited by a gang of professional pickpockets. “It’s a story about people who go off the rails,” she tells me. “I think back then I loved, and still do love, writing about people who are imperfect, or who find life difficult, rather than stock heroes.”

She’s here today to talk about The House of the Lost on the Cape, her adaptation of Sachiko Kashiwaba’s novel about a surrogate family, formed by the trauma of the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake, who inadvertently move into a magic mansion.

“I went location hunting in the Tohoku region with the director, the original creator and producers,” she recalls. “For reference for the house, we stayed at an old folk house in Hyogo Prefecture. In Tohoku, it was helpful for understanding the ambience and topography of the area.” In particular, the assembled creatives realised that a realistically cramped house would not give them the right open space for what she calls a “modern, user-friendly kitchen and living room.” It was important for the story that Yui, the teenage runaway, and Hiyori, the orphaned little girl, should get to play house a bit in an environment that let them breathe.

In Kashiwaba’s original novel, Yui was a much older character, fleeing an abusive husband, but Yoshida’s screenplay turns her into a high-school truant. “I wanted younger viewers, with a lot on their mind, to be part of the audience for this piece,” she remembers, “and I thought that a girl encountering mysterious events would be better as a character, here. I also thought that if a character needed to empathise with Hiyori, we needed someone closer in age to her.”

Hiyori, however, has very little to say in Yoshida’s script, being largely mute for much of the film. Instead, her character is revealed solely through her actions, although Yoshida gracefully assigns her best moment to another’s influence. “I think all it said in my script was something like ‘Hiyori runs out of the building while we hear the sound of a kagura [ritual shrine dance]’ but I believe the director made it even more impressive with the way he shot it.” In fact, the triggered Hiyori runs screaming from the rehearsal room, and has to be consoled by the adults, but the entire sequence is shot by Kawatsura from a distance, as if the agonies of a mere human mean little in the grand landscape of the region.

Yoshida rejects the notion that The House of the Lost on the Cape was also something of a metaphor for lockdown life, since she finished writing the script shortly before the COVID pandemic broke out. “Human emotions do not change with time,” she observes. “You feel sad when your loved one dies, and hurt when you are reproached or derided. No matter which period you depict, as far as there is something that never change, I think that will become a story about ‘now’.”

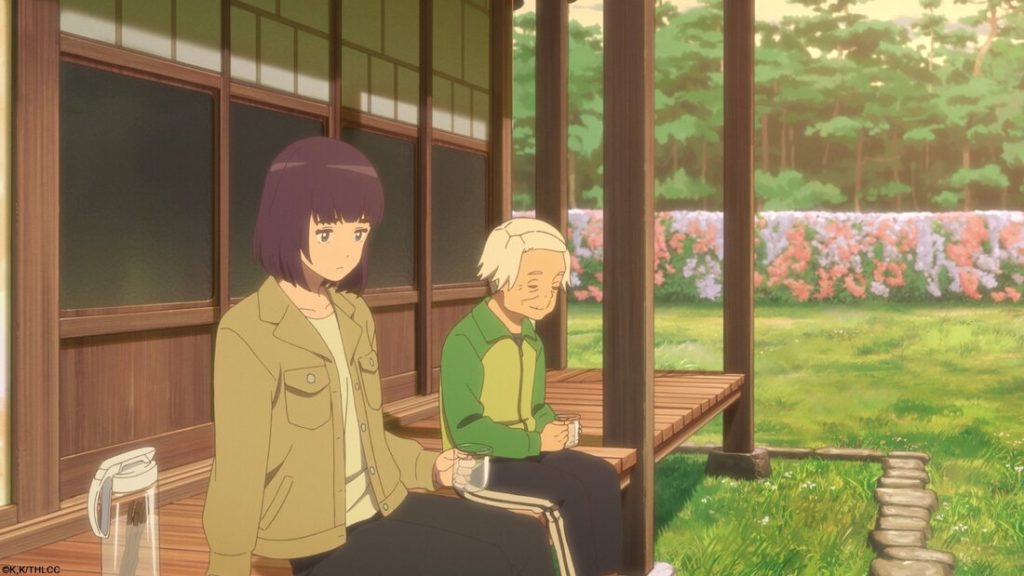

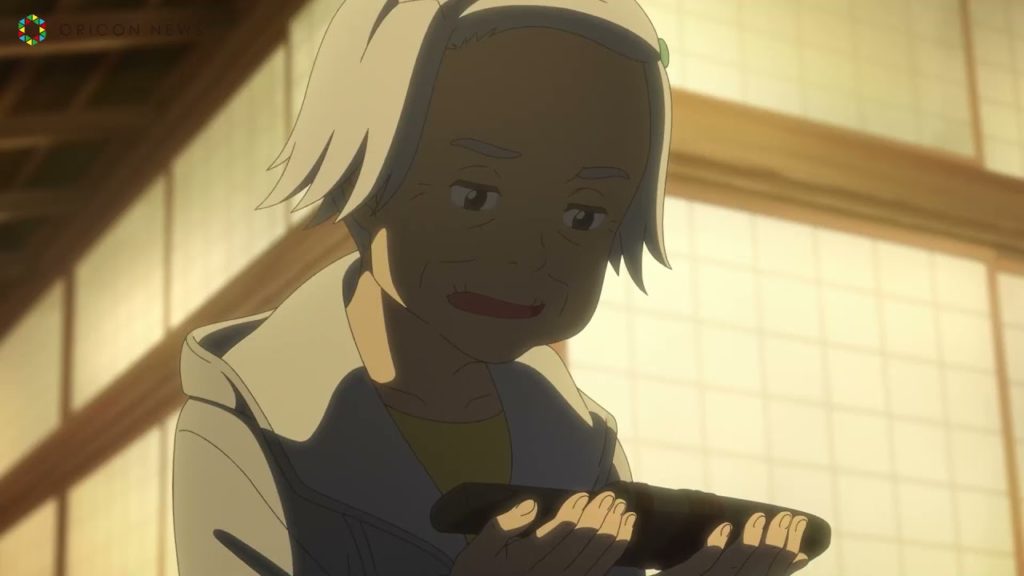

Yoshida was much more hands-on in her depiction of Kiwa, the “family” matriarch, who in the novel is an old lady effectively liberated by the earthquake, as she no longer has to report at an old people’s home. Instead, she gathers the girls under her wing at the haunted mansion, and regales them with folktales of the yokai spirits of northern Japan.

“I wanted to depict Kiwa as one of those rare human beings who can communicate with spirits,” says Yoshida. “Yokai don’t only appear to people who are lost in the mountains, but also to people who are lost in their lives, or who feel lonely. Most yokai are friendly towards humans, but they tend to steer clear because they are afraid that people will be afraid of them, or attack them or try to exploit them.

“Kiwa has lived a lonely life, but encountered yokai when she was a child. In Japan, we have a saying: ‘Children are gods until they are seven years old.’ It is a folk belief that humans can sense the numinous world until they are seven. In this piece, too, I had a background whereby those who had contact with mysterious beings in childhood could also communicate with yokai when they got older.”

After many years adapting the works of others, Yoshida finally seems to have the clout to get some more of her own original scripts made for the screen. She points to last year’s TV series Empire of Seventeens, “my original sci-fi political drama,” set in a future where teenagers are appointed to government positions in an attempt to handle Japan’s aging crisis, as well as “an animated film coming out this autumn that is an original youth story of mine” – meaning Kimi no Iro [“Your Colours”], directed by her frequent collaborator on everything from K-On to A Silent Voice, Naoko Yamada.

But when it comes to making dreams come true, Yoshida is absolutely sure what she would want a magical mansion to be able to do for her.

“I’d like a house that can fly away to anywhere.”

Jonathan Clements is the author of Anime: A History. The House of the Lost on the Cape is released in the UK by Anime Limited.

[ad_2]