[ad_1]

By Andrew Osmond.

Mamoru Oshii, the director of Patlabor the Movie, once described his 1989 film as pop entertainment. Any fan of Oshii, best known for Ghost in the Shell, knows that’s a huge undersell for what is an extremely complex, thoughtful film. But perhaps Oshii was referring to how Patlabor the Movie ticks a great many boxes at once.

It’s a comedy-drama featuring one of the most loveable character ensembles created in anime – not teen students, but a very unorthodox police team who spend their time off duty raising chickens and growing their own food. Patlabor the Movie is also a mystery film, twisty to the point of postmodernism, whose conclusion is a sardonic comment on the state of post-war Japan. But the film’s references are far from exclusively Japanese. For instance, the climax includes a massive homage to an Alfred Hitchcock classic that’s both funny and sinister.

It’s also a most unusual mecha anime. A decade before, Gundam had popularised the idea of the “real robot” anime, treating giant human-shaped big robots as real machines in believable contexts. Patlabor pushes that to its logical end, placing the big robots and their operators in what’s effectively present-day Tokyo, though the film’s dateline is 1999, a decade in the future when Patlabor opened.

In Patlabor’s world, “Labor” robots are used in many fields; most importantly in the film, they’re used for giant construction projects. They’re also used by the police, though a quirk of both Oshii’s Patlabor films is we won’t see much of that till the films’ respective last acts. Up until then, the characters work as old-fashioned investigators. They dig through data, pound the streets, and bump heads with their superiors for asking awkward questions.

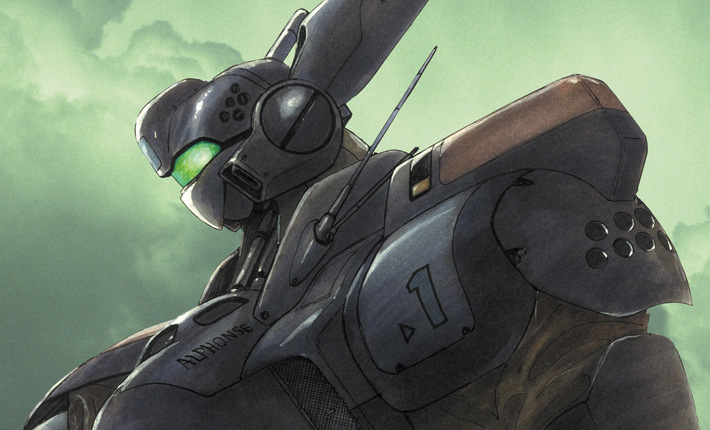

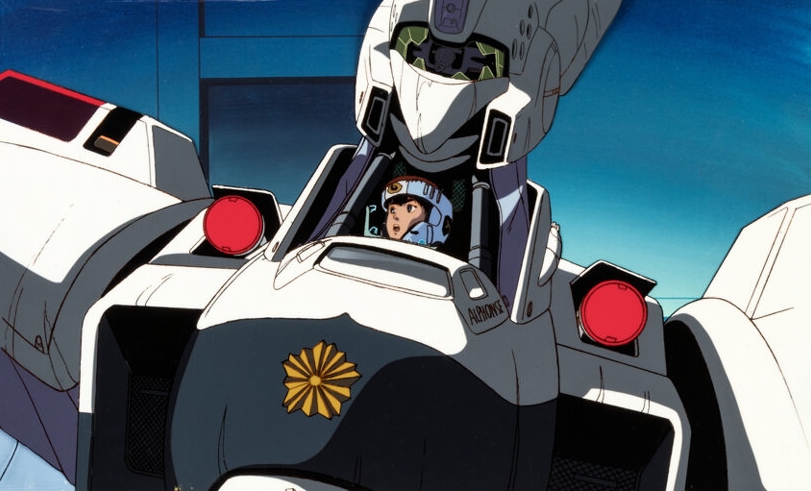

The first film highlights two youngsters in “SV2” – part of Tokyo’s Special Vehicles unit. One of these youngsters is Shinohara, a highly motivated officer. A detail that’s important in the film is that he’s the estranged son of the founder of Japan’s main Labor manufacturer; the company shares his family name, Shinohara. Then there’s Noa, an ingénue cute enough to be an anime mascot and a gifted Labor pilot. She relates to her own Labor, Alphonse, as if it’s a living creature.

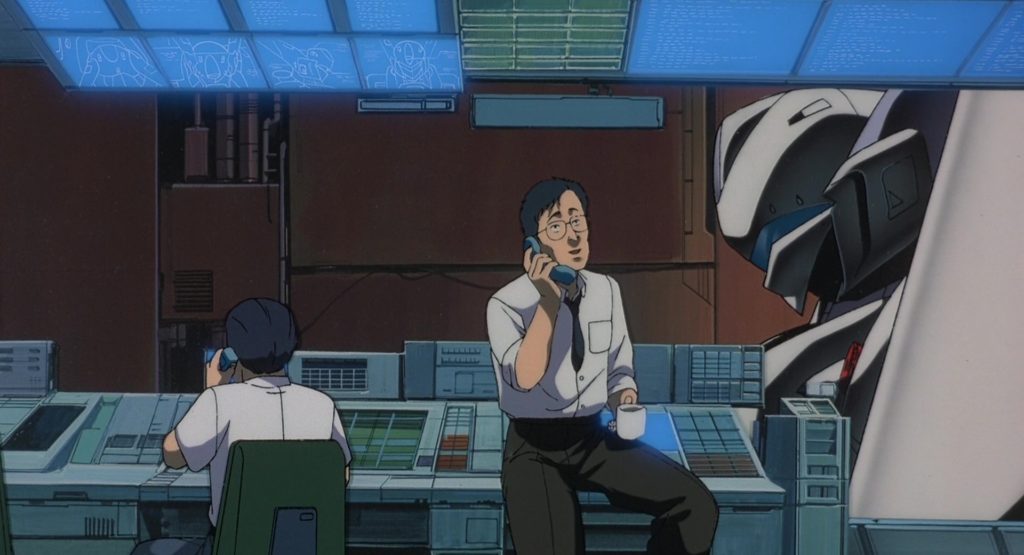

Behind them is Goto, their deceptively languid, amiable, soft-spoken captain, with a mind of Sherlockian sharpness. One of the film’s running jokes is how Goto seems absurdly laid back, when he’s really ten steps ahead of everyone else and manipulating them to do whatever he needs. He has an ally in the regular police, Detective Matsui, who does the gumshoe work. Matsui’s mostly kept apart from the main team, barring an important scene where he discusses his findings with Goto, the men’s mutual respect clear.

Other figures include the overtly comedic Ota, a shouty hair-trigger gun nut, and Yamazaki, a gentle giant archetype who grows food for the team. Two more characters show up later: Shiba, an engineer responsible for the Labors’ upkeep, and Clancy, a New York cop who’s worked with the Patlabor team in the past.

Most of these details are easy to pick up while you’re watching, though Clancy’s sudden arrival may confuse some viewers, especially as she has the tersest of introductions. At a Tokyo airport, she’s asked why she’s come to Japan: “Business or Pleasure?”

“Combat,” she replies.

Patlabor the Movie is spun off from an existing franchise, Patlabor, which established everything that’s outlined above. It was avowedly a team effort, made by a collective called “Headgear.” Apart from Oshii, the team included writer Kazunoi Ito (who wouldd later script Oshii’s Ghost in the Shell), character designer Akemi Takada (who married to Ito for a time), mecha designer Yutaka Izubuchi and manga artist Masami Yuki. It was Yuki who came up with the seed idea for Patlabor.

However, when the first film opened in Japanese in July 1989, there wasn’t much other Patlabor around. The film predated the Patlabor TV anime, which would begin in October that year. The franchise had begun in 1988, as a manga by Yuki and as a seven-part video series – the latter directed mostly by Oshii and sometimes called Patlabor: The Early Days. The video episodes cover the spectrum, from straight action to preposterous farce.

It’s likely, though, that many Japanese viewers who saw the film in 1989 were coming to Patlabor’sworld afresh – it’s still far easier to navigate than the film of Akira. True, Patlabor the Movie gives the impression of being distilled from a series, just because of its diverse parts. When I wrote about the film for Sight & Sound twenty years ago, I commented: “The abrupt shifts between police procedural, high-tech action, character business and Oshii’s philosophising make it feel like a blend of different television episodes.” And yet these parts fit together so well.

In the story, the characters are striving to uncover a master plan set in motion by the film’s antagonist. In an expectation-breaking twist right off, he’s already dead. We see him in the opening moments, stepping smiling off the top of a metal “island” in the middle of Tokyo Bay, and plunging into the waters below. It’s a clear foreshadow of the opening of Ghost in the Shell six years later, with its cyborg heroine plunging off a skyscraper.

In the wake of his death, Labors start going out of control, acting autonomously and even switching themselves back on when their operators don’t want them to. The Patlabor characters realise there’s a computer virus in the Labors’ new operating system… but that’s only the beginning of their adversary’s scheme, planned out far in advance with a diabolical end game. This adversary is a programmer called Eiichi Hoba – “E. Hoba,” nicknamed “Jehovah,” and his name is for more than play.

The underlying subject of the film is the infrastructure of post-war Japan. In 1974, Roman Polanski made the film Chinatown, whose plot revolved around the supply of water through aqueducts to the parched city of Los Angeles. The Patlabor franchise is also all about water. It revolves around Japan’s projects to reclaim land from the sea, which go back centuries, especially in the Tokyo area. The development of Tokyo Bay was especially topical when Patlabor began in the late 1980s.

In An Armchair Traveller’s History of Tokyo, Jonathan Clements described how at that time, “The Tokyo government had poured money into its harbour district, announcing a huge docklands renewal initiative… The portside development of the artificial island Odaiba was expected to be a fantastic opportunity for business real estate.” British readers may think of the development of London’s Docklands not long before; it was the backdrop for another classic crime film, The Long Good Friday.

Patlabor the Movie does indeed show the business interests involved in such development. Midway through the film, young Shinohara is maddened to learn the scandal he’s found is being carefully covered up by the authorities. This leads to an outburst that explodes the film’s style, with Shinohara’s screaming face in “fish eye lens” close-up and giant-sized police emblems shaking with rage. It’s a familiar conspiracy-thriller scene, ramped up to hilarious cartoon extremes.

But Oshii’s interest in the situation runs far deeper. He’s concerned about the spiritual consequences of these building projects, the implications of reshaping Japan as an end in itself, what it means for Japan’s heritage and memory. This strand is unspooled in the multiple languid scenes of Detective Matsui, investigating Hoba’s background for Goto. Matsui explores through endless beautifully-drawn scenes of a “lost” Tokyo that’s scheduled for imminent demolition. There are dried-up canals, empty cavernous storehouses and mountains of junk.

These scenes showcase Oshii’s love for strange, quiet, melancholically beautiful spaces. Think of the dark stone city in Angel’s Egg or the giant flooded arena and abandoned museum that host duels in Ghost in the Shell. In Patlabor the Movie, the “lost Tokyo” storyboards and backgrounds were based on photos taken by Haruhiko Higami. Later, Higami would scout a Hong Kong enclave called Kowloon Walled City; these photos were the basis for the “old city” scenes in Oshii’s Ghost.

Interviewed by the website 032c, Stefan Riekeles, the curator of the “Anime Architecture” museum exhibition, explained what lay behind the scenery in Patlabor: The Movie. “Tokyo was once a lagoon city with many canals surrounding the Imperial Palace. Most of the channels, dating back to the Edo period, were filled in the 1960s. As local research, Oshii and his team criss-crossed Tokyo by boat through remaining old channels to find new, unusual perspectives and hidden views.”

Far more than background colour, these hidden landscapes are a key part of Hoba’s design in the story. Hoba wants the police to see them, in the same way as conventional film villains force the police to see their gory handiwork. Hoba’s plan is far more elegant than butchery. It emerges that he’s aiming to teach the investigators a lesson about what happens when a society forgets its history. It’s a lesson like that in Alex Kerr’s book Dogs and Demons: The Fall of Modern Japan; this is a furious polemic about Japan trashing its heritage, its pointlessly monumental building projects, the damming of its waters.

This is not just a concern in Patlabor; it also resonates in other popular anime. “We are inhabitants of an ancient island nation… Our place is the past and in history. People who have no sense of history, or ethnic groups that have forgotten their past, are destined to disappear like the short-lived mayfly.” So declared Hayao Miyazaki in his original project proposal for Spirited Away, a film that’s all about Japan’s hidden heritage, abjected by modernity. More recently, Makoto Shinkai’s Weathering with You ends with Tokyo’s blockbuster reclamation projects – the island of Odaiba, the Rainbow Bridge – sunken underwater again, while an old woman reflects that’s how Tokyo used to be.

In Patlabor, one of the best jokes in the film is also the most acid, as we find out how Hoba has managed to turn Tokyo’s high-rise skyline into an apocalyptic weapon – a brilliant attack on modern architecture. As in the sequel Patlabor 2, you come out of the film with the strong sense that Oshii sides with the “villain” all the time. There’s a lovely moment when a female police captain Shinobu listens to Goto lay out the brilliance of Hoba’s scheme. Then she remarks that Goto looks positively giddy talking about it.

Indeed, for all the twists that are revealed in the story, there’s one twist that might occur to you at the end. Just suppose… What if Hoba was just an ordinary guy who met a tragic end, and who never created the film’s masterplan at all? Suppose he was just set up as a scapegoat by the real mastermind, like many of the heavies in Oshii’s Ghost in the Shell? After all, we can see there’s someone in Patlabor who’s clever enough to have orchestrated it all.

But while it’s funny to wonder if Goto might be the film’s real villain, playing both sides of the chess board, the figure of Hoba fits with Oshii’s other anime. He’s one of the director’s infuriatingly elusive adversaries, in line with Tsuge in Patlabor 2, Teacher in The Sky Crawlers and the completely impersonal Locus Solus company in Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence. Most of all, Hoba foreshadows the Puppet Master in the first Ghost.

Like the Puppet Master, Hoba seemingly sees his humanity as a disposable façade. His real existence in the film is as a Trojan Horse computer virus, multiplying merrily through the material world. And if you think this virus is only metaphorically alive, remember that not everyone sees life the same way. Noa, for one, certainly sees her mecha Alphonse as alive. Hoba and Oshii love Old Testament stories and quotes, but the film mixes them with an implied pantheism that any Japanese viewer would recognise.

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films. Patlabor the Movie is screening at this year’s Scotland Loves Anime.

Andrew Osmond, Mamoru Oshii

[ad_2]