[ad_1]

Moncage is one of those puzzle games of intermittent lightbulb moments. One minute you see solutions with perfect clarity. The next you’re left scratching your head and wondering how the heck you’re meant to proceed. It wouldn’t be much of a puzzle game if there weren’t a few moments like this, of course, but when you’re playing out mechanical riddles across five possible surfaces – in this case, the sides and top of a rotatable cube – Moncage can sometimes veer into giving you a complete cerebral blackout, leaving you at an impasse until you consult its series of timed hints (or, if you’re really desperate, an in-game video solution).

When the lightbulb pings into bright, brilliant existence, though, Moncage can be truly illuminating. As you rotate, prod and investigate its five little vignettes to line-up matching bits of scenery in one tile to affect the corresponding bit in another, Optillusion’s debut game harks back to the best bits from Fireproof Studios’ The Room series. It’s a beautifully crafted little thing, and it builds on its ideas to create some genuinely standout moments of optical wizardry. If only the story it was trying to tell was half so elegant.

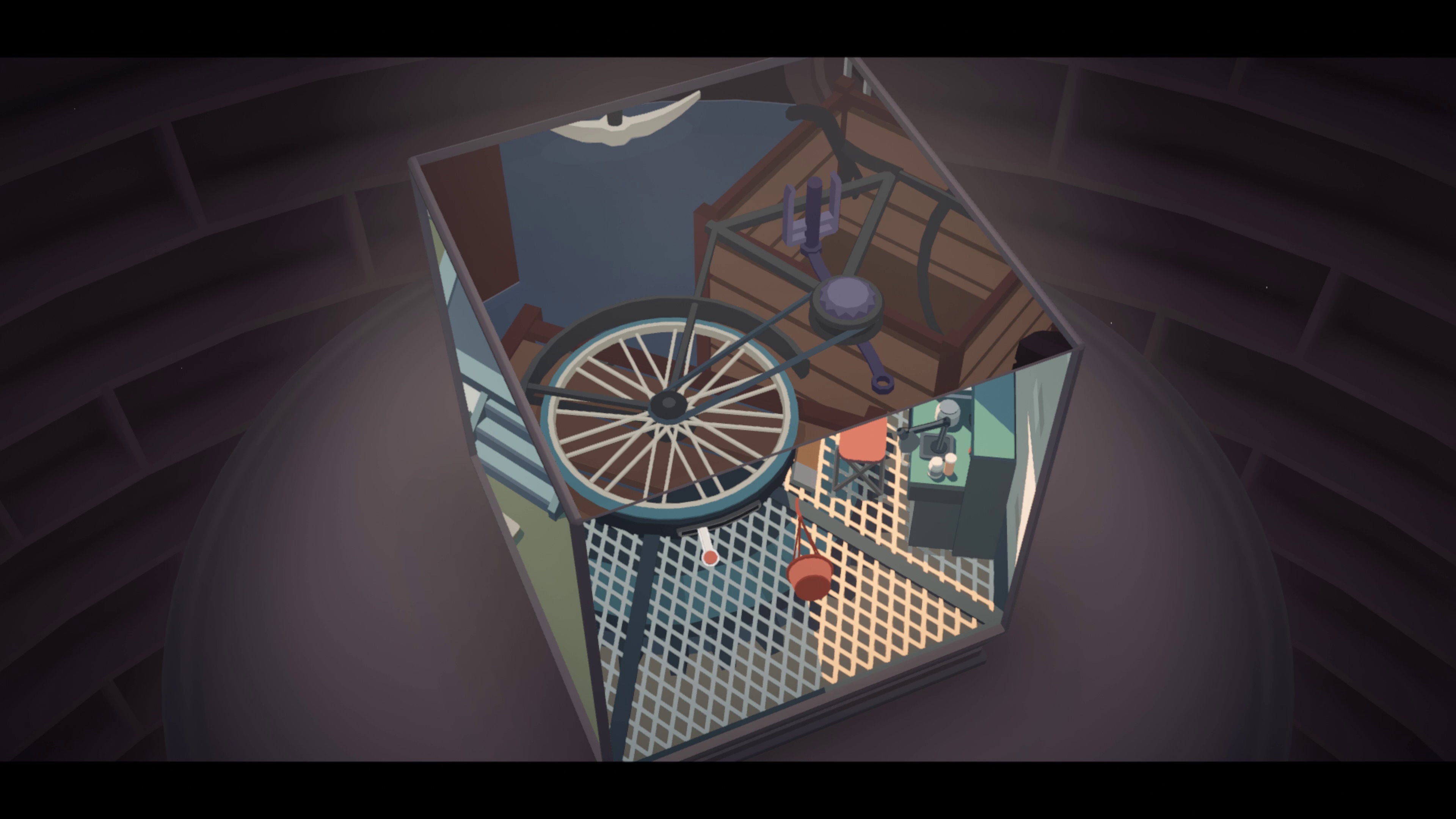

You begin in a lighthouse. While there aren’t as many levers and switches to twist and tug as The Room’s 3D puzzle boxes, Moncage still manages to feel like an interactive Rubik’s cube on your monitor. You’ll rotate each scene with a swipe of your mouse, click to interact with its various objects and double tap particularly busy areas to zoom in and out of them. Despite every side showing a different scene, they all have elements in common, and the puzzley bit is working out how to line them all up to move through the story.

To give an early example, you might use the blue trapdoor in the floor of the lighthouse to form the other half of a broken bridge in the snowy urban factory setting on the tile next door. Or maybe that bicycle wheel in the flooded storage room – which appears on another side of the cube after opening said trapdoor – can be combined with the very similar-looking mechanical lever in the lighthouse’s central pillar to let you change the angle of the pedal – which in turn can then be used to unlock a gate in that factory tile I just mentioned.

It’s all about using perspective to your advantage, and at its best Moncage feels like a digital origami fortune teller, with deft finger-work revealing new and surprising things about these dynamic environments. There are too many standout set pieces to mention here, nor would we want to spoil the surprise of them either. But special mention must go to the war-time sequence where you’re shifting the cube in real-time to transport a bomb from a cannon across all five sides to get it to its intended destination.

At times like these, Moncage is one series of lightbulb moments after another. It’s brilliantly satisfying stuff, even if the occasional mistimed blunder can mean a lot of repetitive setup when trying again. But if you’re wondering how we got from a lovely idyllic lighthouse to the carnage of cannons and warfare, Moncage may not provide the answers you’re looking for. Its story is told vaguely through the scenes presented in the cube, but even the more pointed narrative beats captured in the collectable photographs you’ll find in hidden nooks and crannies fail to convey a sense of cohesion and deeper meaning.

As I understood it, it’s a tale about a father and son who seemingly become estranged after the son goes off to fight in a military conflict that’s somehow both modern day and reminiscent of World War II. As he recovers and re-enters society after an injury, he drowns his sorrows in alcohol and descends into despair. Then (and here’s where Moncage lost me slightly), he seems to find redemption by adopting a young boy, and eventually the two of them return to his father’s lighthouse to begin life anew – although when the game ends on the same suitcase of toys and belongings as the one you open at the start, it also implies some nightmarish cycle of families torn apart and sewn back together again after a series of horrific conflicts.

Trouble is, Moncage just doesn’t have anything interesting to say about either the father and son’s relationship, or the war that drives them apart. Its abstract puzzles are clever for cleverness’ sake rather than the story, and they rarely serve to teach you anything about the scene in question or say anything deeper about its place in the narrative (although I will say the way some objects in the bar scene are transformed into war images when viewed through a beer glass is particularly well done).

What’s more, the timelessness of the whole thing makes it difficult to place and contextualise in a way that might provide us with any sort of comment or criticism on its series of events. This is a place where drones, cannons, tanks and colour TV all jostle together in the same head space, and I came away wondering what I was meant to take from it all, especially after it pulled the whole son becoming the father and father becoming the son nonsense. That was just one comic book leap too far for me.

Combine that with a couple of infuriating puzzles that left me completely stumped, not to mention a hint system that’s often as patronising as it is helpful (especially when it doesn’t register which parts of the puzzle you’ve already completed), and Moncage can sometimes feel like it’s trying to be too clever for its own good. At three hours, it certainly doesn’t outstay its welcome, but its muddled story means it doesn’t stay long in the memory either. Still, if you’re in it for the love of the puzzles, then there’s definitely a lot to admire here, and I reckon the ingenuity of its kaleidoscopic cube is enough to make up for its underwhelming story. It might not be quite up there with The Room as an all-time puzzle classic, but it’s probably the closest we’ve come to a spiritual successor in quite some time.

[ad_2]

Bonuses for new players

Bonuses for new players