[ad_1]

By Andrew Osmond.

Liz and the Blue Bird was released in Japan in April 2018, less than two years after A Silent Voice. It was an ideal film for uniting two sets of viewers; those who’d become aware of Naoko Yamada through A Silent Voice, and those who loved the series she’d been involved with previously, such as K-ON! and Sound! Euphonium.

Those viewers overlapped anyway, but Liz feels both innovative and populist. It often tells its emotional story with no need for words, but its quiet intensity is leavened by cute moments and scenes that celebrate daily life, things that were rather lacking in Silent Voice. Unlike that film, Liz isn’t a story about guilt, but about longing and yearning, the implications of a teen needing to grow, and about how two friends may be extraordinarily close while crucially misunderstanding one another.

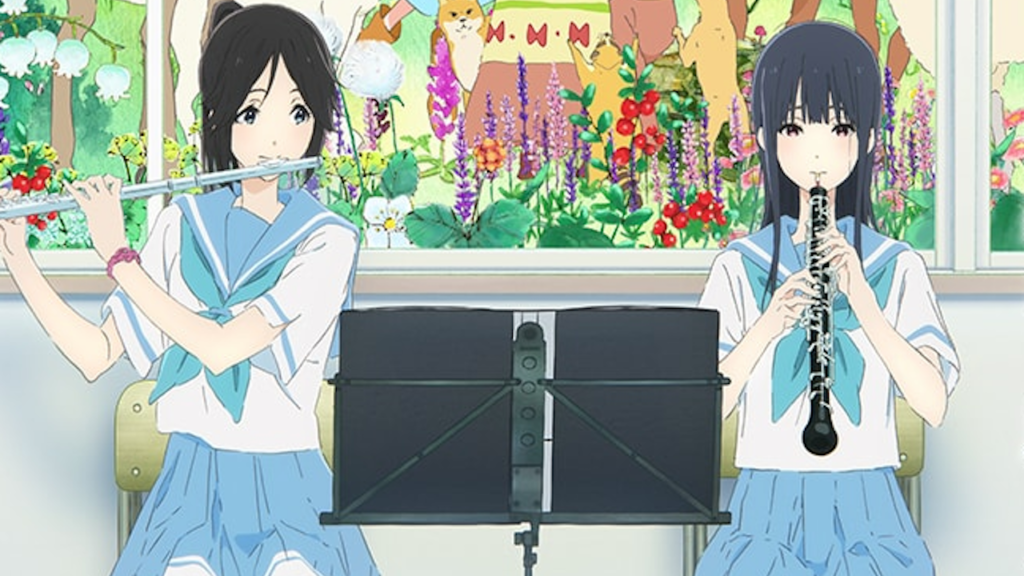

These friends are girls, Mizore, who’s the subdued viewpoint character, and Nozomi. They’re both in their high school band, and recognised as among its top talents. Mizore plays the oboe and Nozomi the flute. The band’s current project is a musical piece called Liz and the Blue Bird, which involves a duet where the characters are represented by an oboe and flute respectively. It should be ideal for the two girls, but Mizore has issues with the piece, bound up with her emotional life.

For Mizore loves Nozomi, and is compelled to think of the music piece of a reflection of their relationship. Mizore has never confessed her feelings to her friend, who treats her with a warmth and fondness that Mizore treasures. But they’re now both in their last year of school, and their future is uncertain. At one point, Nozomi sees Mizore’s brochure about a music school, and says she might apply there too. But is she being serious, or have any awareness what that would mean for her friend?

The girls are light and shadow. Nozomi is the popular, cheerful girl, Mizore the silent, unsmiling type, yet her sombre expressions and glances suggest a bottomless well. Mizore has affinities with another character animated by Kyoto Animation in the same year as Liz, Violet Evergarden.

Liz’s almost wordless first minutes paint the girls’ relationship exquisitely. Mizore waits for Nozomi outside school on a misty morning, visibly struggling for composure. Her eyes tremble liquidly, she clenches her fists and kicks out her feet. Then Nozomi arrives smiling, her ponytail swaying like a metronome; she’s light-footed, completely at her ease.

The next minutes show the girls walking through school, Mizore hanging behind Nozomi, out of step with her idol in a way that’s exquisitely poignant. Cartoon fans might think of the mushroom dance in Disney’s Fantasia, with the little mushroom beguilingly out of time with his taller peers. The Liz sequence is accompanied by a cascading piano by Kensuke Ushio, very in line with his Silent Voice work.

Liz and the Blue Bird is one of several anime films of the 2010s that centred girls’ romantically-tinged insecurities. In 2015, there was the chronically repressed heroine of Anthem of the Heart, written by Mari Okada. The same year, one of the kooky girls in Shunji Iwai’s The Case of Hana and Alice is petrified that she’s done something terrible to her ex-boyfriend. A year earlier, Ghibli’s When Marnie Was There was based on a British book; it’s another story of a quiet reserved girl falling in love with her extrovert, laughing soulmate.

As with Marnie, some viewers of Liz will be infuriated that the protagonist – in this case Mizore – isn’t explicitly confirmed as gay. This issue goes far wider than Liz; there were similar arguments about the anime film Project A-Ko three decades ago. The debut Sound! Euphonium novel, which created the “world” where Liz is set, was similarly non-committal. “Concert bands were a special place,” author Ayano Takeda wrote in the first pages.

“The ratio of girls to boys was usually around nine to one, but strictly speaking, it was often even more lopsided than that. So it was not uncommon for girls to end up idolizing someone of their own gender. The objects of such infatuated gazes – gazes that were much too fervid to be interpreted as simple envy – tended to either radiate pure femininity or possess a boyish stylishness.”

On screen, however, the power of Mizore’s longing gaze far outweighs Takeda’s commentary, which was dropped by Kyoto Animation anyway. The studio first took on Takeda’s books in a 2015 TV series also called Sound! Euphonium, directed by Yamada and Tatsuya Ishihara. Tonally, the series is very different from Liz. It’s about the same music club, but highlights other characters – Mizore and Nozomi are barely glimpsed in season one. The series is a conventional (though excellent) entertainment, a mix of comedy and drama without the intensity that Liz takes from Silent Voice… though the series also has an evocative bond between two girls.

A second Sound! Euphonium season followed in 2016, where Mizore and Nozomi were introduced properly, though they were still only support characters. Both seasons were compiled into films (2016 and 2017), followed by a film sequel in 2019, subtitled Our Promise: A Brand New Day.

However, Liz purposefully stands apart from the rest of the franchise. You might compare it to the 1979 anime film Castle of Cagliostro; it was part of the endless Lupin franchise, but was a very distinct version of Lupin, romanticised by director Hayao Miyazaki. In Liz, the characters from the “main” Sound! Euphonium series are themselves reduced to bit-parts; for instance, series heroine Kumiko and her soulmate Reina are glimpsed through a window, practicing together.

But as noted earlier, Liz also has cute interludes where other girls in the band are shown chatting over daily minutiae. As well as lightening the film, these moments provide a bridge between Liz and Kyoto Animation’s past series, including Sound! Euphonium itself. Then there are the film’s “story in a story” scenes, in which Mizore reads a picture-book version of Liz and the Blue Bird. These scenes are painted in bright fairy-tale colours, reminiscent of the old World Masterpiece Theatre anime serials like Anne of Green Gables in the 1970s. The story itself seems simple… though one point of Liz is that different people, relating the story to their own lives, can read it in entirely different ways.

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films. Liz and the Blue Bird is released in the UK by Anime Limited.

[ad_2]