[ad_1]

By Jonathan Clements.

Tom Mes’s new book begins in 2022 with Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s Drive My Car winning an Oscar, followed by a flood of gushing articles about how it was going to “change Japanese cinema.” He notes that this relatively minor art-house film was never going to rock any boats in its native Japan, and goes on to point out that if you wanted something really transformative in Japanese film, you should consider something like the 60-minute 1989 straight-to-video Crime Hunter (above) which kick-started an entire new distribution medium. His point, as with Alexander Zahlten’s similar claim for Tusk of Evil, is that critics often ignore game-changing, structural moments, talking earnestly about “popular culture” while disregarding what is actually popular. This is merely the opening argument for a book dedicated to Japan’s “V-cinema” market, regarded by the mainstream as straight-to-video tosh, thick-eared actioners, under-the-counter smut, rubber-monster hokum and, er… Japanese cartoons.

Mes starts by examining the fervid politicking of international film festivals, which formed the main entry for Japanese cinema into foreign markets in the days before video. Here, he provocatively considers Nagamasa and Kashiko Kawakita, the distributors who brought so many Japanese films to Europe, not as pioneers but as gatekeepers, inevitably steering foreigners’ ideas of what a Japanese film looked like.

I should stress that this is not an attack on the Kawakitas – more of a playful reimagining of their activities as visualised from the bottom up. Undoubtedly, they were instrumental in bringing hundreds of Japanese films overseas. In doing so, by simple dint of their position in the market, they also didn’t-bring many more. He points out, for example, the shouting match that developed between rival French festivals over whether Kurosawa or Mizoguchi was the greatest director ever, and wryly notes that “the Parisian critics had to fish from a sparsely populated pool.”

Imagine, if you will, a big-name film festival. It’s easy if you try. Bragging about how they’re going to put on a massive celebration of Japanese cinema… and then putting on the usual Seven Samurai, Rashomon, a bit of Mizoguchi, a bit of Ozu… and maybe one of those Miyazaki cartoons for the kiddies. Well, why wouldn’t they? They would be remiss, if they were supposed to be celebrating Japanese cinema, if they didn’t include some of the greatest films ever made.

Mes points to a tendency among critics and festivals to laud the achievements of other critics and festivals, rather than those of the films and filmmakers they are supposed to be championing. And, again, partly this is only natural – it is very difficult to persuade audiences to try something new, or different, or foreign, particularly in the days when such a customer journey would involve getting off the sofa, going to a cinema, paying your money and hoping it wouldn’t be awful. A good festival valuably curates that experience, offering audiences the chance to experience a bunch of films of a particular ilk, and encouraging them to try something else while they’re there. An unstated hope of Scotland Loves Anime, for example, is that while the films are supposedly intended for an audience of dedicated anime fans, the true victory at any screening is the presence of 30% walk-ins by members of the public.

Mes finds in Rashomon (above) the perfect analogy – there’s truth in there, but so much discourse around it that nobody knows what the truth is any more. The film itself was once dissed by its own studio boss, Masaichi Nagata, as “incomprehensible”, and yet within a few months, Nagata himself was parading around European film festivals, glad-handing local distributors and screening the film as a shining example of Japanese cinema. Fatefully, one of the screenings in Venice in 1951 was attended by a reporter for Sight & Sound, profoundly out of her depth, unable to understand either the original Japanese or the Italian subtitles, who instead attempted to describe the film in hand-wavingly pretentious terms that would go on to colour much Anglophone writing about Japanese film for years to come.

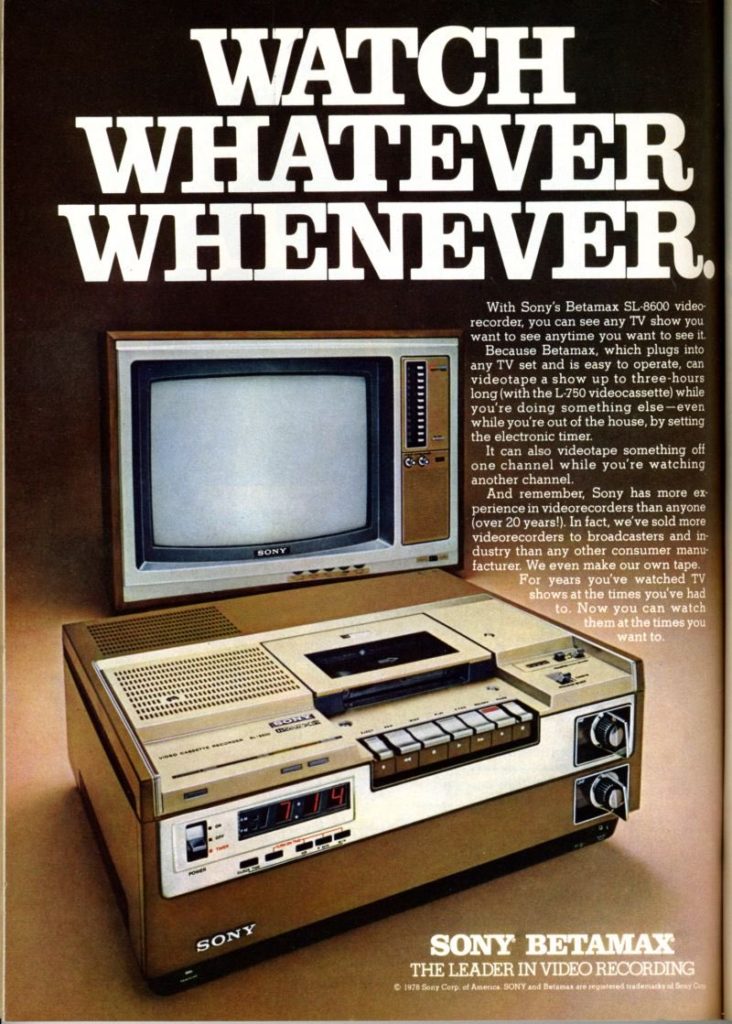

Mes goes on to present an informative history of the video cassette, centred around the watershed moment when a copywriter for Sony thought a good advertising tagline would be “Now you don’t have to miss Kojak because you’re watching Columbo.” Both shows were produced by Universal, so it was assumed that the studio wouldn’t mind having two of its primetime serials mentioned. Instead, Universal sued Sony for creating technology that made it possible to “steal” their shows. The infamous Betamax Case dragged on for several years, and it was only after a Supreme Court ruling in favour of time-shifting that video was truly permitted to go mainstream. The “first sale doctrine” that makes it legal for you to rent or re-sell “the physical manifestation of a copyright work” to someone else, soon created a boom in video rental stores.

Meanwhile, in Japan, the big studios were getting ready for video before it even arrived. Toho set up a video division in 1969; Toei in 1970, in anticipation of there being a video business within a few years. Nikkatsu, in particular, was quick off the mark, marketing pre-recorded tapes for use “on ships and in love hotels”, immediately identifying the potential of the smut market. But it was Toho that was the most cunning, harvesting data from rentals at the Toho Video Shop, in order determine the content of future productions. With an average rental of only two tapes a day for much of its four-year existence, the Toho Video Shop statistics might have been skewed by a tiny handful of early-adopting male customers, as if Hollywood film production were steered exclusively on the rental choices of Quentin Tarantino and Kim Newman, or as if me repeatedly typing “redhead discussing chess moves in her underwear” into Netflix’s search function, every day for year, was the sole cause of The Queen’s Gambit getting made (I did not actually do this).

Toei, too, was remarkably hands-on with its customer research, with executive Tatsu Yoshida buttonholing renters at stores to ask them about their purchases and viewing habits. Mes points to Crime Hunter as a film deliberately crafted in response to these results, supposedly un-fast-forwardable, although, again, the wording of his policy decisions strongly suggest that he was basing them on a miniscule handful of conversations with whichever randos happened to be standing in the rental queue at the end of his lunch-hour. Before long, however, Yoshida was pitching projects to rental store owners before they went into production, allowing Toei to predict with reasonable accuracy the number of sales a video would have before they even shot it. Such a metric also applies to the anime world, where in 1989, the year that rental stores reached their 16,000-site peak, titles such as Story of Riki and Angel Cop could be sure of at least one £100 tape sold to each one.

Mes notes that early straight-to-video anime production (the OAVs or OVAs – there is a distinction but nobody seems to care anymore) was split between some titles like Dallos (below), that were essentially “failed” TV pitches, and others, like the entire hentai genre, that enthusiastically embraced the potential presented by a new distribution medium that did not have to go through the old channels. Or one executive puts it: “In TV drama we must follow the logic that the story needs to be understood by 80-90% of Japanese citizens. This is a very strict rule. V-Cinema has no such rule…”

The number of film titles being produced “straight-to-video” outstripped films being released in cinemas as early as 1985. This had a huge impact on Japanese animation, in an age that saw its rapid expansion into new, maturer and obscurer niches. A similar shift attended Japanese live-action film, Mes’s main subject.

The bursting of the economic bubble in 1990 caused a degree of shake-out and bankruptcies, but V-cinema itself barrelled on along, buoyed up by the thirst for new content from rental stores and new TV channels. Mes discusses some of the stars of the video genre who never quite broke out of it, but enjoyed long-term careers, sometimes cranking out fifteen films a year. He also alludes to similar successes behind the camera, including the director Takashi Miike, on whom Mes can reasonably be said to be the world expert. Miike, of course, broke out of the V-cinema world, in part because of the critical and gatekeeping disruptions that Mes outlines. It doesn’t matter so much if Miike’s films were beneath the notice of stuffy old festival programmers; it matters if there were two dozen of them in a video-shop bargain bin on the day that a young Tom Mes was looking for something new to write about.

Mes humbly avoids mentioning that his account of the “challenge of video” is also a deeply personal memoir, in which he wanders Zelig-like, through the video stores and cinema premieres, festivals and book launches that accrue like limescale around the films themselves. He was the co-founder with Jasper Sharp of the influential website Midnight Eye (2001-15), which deliberately curated many such films – notably, both have undergone a career path from fanboys to critics, to academics, to curators, forming the new old guard in the medium where they were once young whipper-snappers.

I first met Mes at the Udine Far East Film Festival in 2002, where we were both young thirty-somethings, seeing our own media interests slowly trumping those of the older generation, not necessarily because the old gatekeepers were gone, but simply because we’d stumbled across another gate. In this book, Mes gestures through the portal at the seething mass of other titles that were often overlooked, such as multiple 1990s tales of Robin-Hood-yakuza, system-beating gamblers and proletarian struggles, aimed at an audience of “everyday men with families, debts to pay off and no job security.”

Mes goes on to talk about the internationalisation of V-Cinema, at first in terms of the American straight-to-video product insinuating itself into the Japanese market in the form of the rather good American Yakuza (pictured), starring a young Viggo Mortensen. He looks at the overseas market for Japanese video as an initially unexpected bonus, but also returns to film festival gatekeeping, with a discussion over the feeding frenzies around Takeshi Kitano and Shinya Tsukamoto.

He reminds the historically minded reader that Island World/ICA Projects/Manga Entertainment, even as it pushed the seminal anime Akira on the UK public, also tried to interest video buyers in live-action works such as Shinya Tsukamoto’s Tetsuo (below), making “V-cinema” very much part of the story of anime in the UK. He also points to Tartan’s Asia Extreme label as an important player in the game of bringing Japanese entertainment to UK audiences.

There are a number of other anime and manga connections nestling below the surface. Mes mentions the Scary True Stories series, for example, written by Armitage III’s Chiaki Konaka, and based on the manga anthology magazine of the same name, which continues to be published to this day, notably for a female readership. He also charts the rise of “J-horror”, which had its origins in the throwaway pulps of V-cinema, but soon migrated to cinema, international acclaim, and American remakes.

His closing chapter deals with the implications of all this for academia – whether it is desirable, or necessary, or deluded, or even possible to include a fair and frank discussion of V-cinema in the film studies curriculum. Modern-day curators wring their hands about whether it is elitist to create an all-new canon (a new round of gate-keeping, if you will), or if it is vital to have arguments such as Mes’s in place before the next generation is drowned by “Streamageddon”. He also deals briefly with the game-changing properties of DVD, which was not only cheaper to produce and could be racked on the same space in larger quantities, but ruined the livelihoods of many small video stores that had invested in VHS libraries and could not afford to upgrade to the new technology. He covers the then-controversial acquisition by the Yale University Library of a collection of video tosh in 2015 (the same institution is also home to all my old dorama DVDs and VCDs, after Aaron Gerow offered to take them off my hands) and discusses the long-term curatorial issues of preserving content on the antiquated and increasingly dilapidated VHS format.

“It has,” he notes, “not only played an active part in shaping canons, it may yet serve a vital role in reshaping the ways we study film, urging us to reconsider our inflections as film scholars and as gatekeepers – and to examine the very tools of our craft.”

Jonathan Clements is the author of Anime: A History. Japanese Film and the Challenge of Video by Tom Mes is out now from Routledge.

[ad_2]