[ad_1]

By Tim Wilmot.

By the mid-1970s, the decline of the Japanese studio system had led to the rise of pinku eiga, low-budget soft porn movies that were targeted at a male theatre-going audience. However, this transition towards films dominated by eroticism had already begun almost a decade earlier for auteur filmmaker Yasuzo Masumura. The director had continued to work for the Daiei studio throughout the 1960s whereas many other filmmakers of the Japanese New Wave opted for independent production. Despite the confines of a commercial studio system, Masumura managed to utilise the resources at Daiei’s disposal to produce several sexually provocative works throughout the decade, including his 1966 film, Irezumi.

Otsuya (Ayako Wakao) flees from her wealthy merchant parents with her lover, Shinsuke (Akio Hasegawa), hoping to elope. The couple take shelter with family friend Gonji (Fujio Suga) and continue to indulge in a passionate romance. However, deceit and betrayal see Otsuya sold into prostitution at a local geisha house, where she forcibly receives a tattoo of a giant, human-faced spider on her back. Far from being beaten by the horrific marking, Otsuya instead revels in her new role and uses her powers of seduction to plot vengeance against those who have wronged her.

Irezumi is one of three Masumura films to be adapted from the works of novelist Junichiro Tanizaki, the other two being Manji (1964) and A Fool’s Love (1967). The original short story, entitled Shisei (“The Tattooer”), was published in 1910 and would later be lumped in with the “erotic grotesque nonsense” literature that became prominent in the 1930s. Masumura regarded eroticism as the most human of characteristics, so it is no surprise that he developed a fondness for Tanizaki’s works. The adapted screenplay from Kaneto Shindo, who incidentally directed the erotically-driven horror masterpiece Onibaba (1964), sees the story shift focus from the mysterious tattoo artist Seikichi to the frightening and self-serving Otsuya.

The film’s Edo period setting not only allows for some typically stunning costuming, with Otsuya sporting several strikingly coloured kimonos, but it also makes way for an eerie and atmospheric feel. While by no means an all-out horror, there are several scenes of shocking violence, the execution of which is over-the-top and bloody. There are no honourable exits to be found here, as anyone who does bite the bullet does so in an ugly and clumsy manner. There’s even a tinge of the supernatural as the stunning spider tattoo on Otsuya’s back is frequently blamed for the geisha’s increasingly despicable actions. The alluring concoction of eroticism, violence, and superstition means that despite being one of the more slowly paced Masumura films, Irezumi retains a sense of passion and intrigue that makes it an enthralling watch.

With Irezumi, Masumura further leads the charge for individualism in film from the perspective of female characters. Up until this point in his career, Masumura had made a habit of presenting audiences with protagonists who railed against the caricature of the reserved and self-sacrificing Japanese woman and were instead more overtly passionate specimens. The director believed that women are inherently the most “human” whereas men, by contrast, are not truly free and live only for the opposite sex. This belief is reflected throughout Irezumi as Otsuya is surrounded by submissive men that are distinctly lacking in agency. From the cowardly Shinsuke to the despicable Gonji, these men act only to please Otsuya in the hope that she might return their affection. The cruelty with which she toys with these would-be lovers is just one of the ways that she becomes such an influential and powerful figure. Otsuya’s calculated vengeance against these hapless men makes it unclear whether she is a liberated woman exacting her free will or a deceitful villainess whose innocence has been lost. Such ambiguity of character further demonstrates the extent to which Masumura was committed to studying the individual rather than placing focus on the world around them.

The film marks one of many collaborations between Masumura and star actor Ayako Wakao. Making her feature debut for Daiei in 1952, Wakao would go on to make twenty films with the director, the first of which being his anti-Ozu effort, The Blue Sky Maiden (1957). A prolific actress, who starred in over 150 films before predominantly featuring on television from 1970, she is one of the most important collaborators of Masumura’s career, with her sensual and domineering characters being some of the most empowered female figures in the history of Japanese cinema. The case is no different in Irezumi, with the scheming Otsuya using her sexuality, charm, and passion for revenge on those that have wronged her. Such presence and power are only made possible through Wakao’s brave performance, which is undoubtedly one of her most iconic. Interestingly, Wakao and Masumura experienced a strained relationship; the director labelled her a “selfish and calculating woman”, while Wakao described working with the filmmaker as being “a kind of battle”. A battle though it may have been, with results as bold and memorable as Irezumi, it appears to have been one worth fighting.

From the opening moments, it’s apparent that Irezumi will be a visually striking affair, not in the least because of the pristine 4K restoration. The bold use of colour, particularly red, is made all the better for the fact that it often contrasts with dimly lit backgrounds. This distinct visual style is explored at length by Daisuke Miyao, whose video essay on Kazuo Miyagawa introduces us to the cinematographer’s theme of clarity and contrast. Miyagawa, who also worked with Kenji Mizoguchi and Akira Kurosawa, believed the development of colour film to be “the most shocking” of his career, yet managed to maintain his shooting approach through the transition from black and white.

A written essay from Miyao featured in an accompanying booklet sees the University of California professor discuss the significance of Miyagawa’s Kyoto upbringing on his obsession with clarity and contrast, as well as the cinematographer’s European and Hollywood influences from 1930s musicals to F.W. Murnau. Also featured in this booklet is writing from the University of Chicago’s Thomas Lamarre, who explores the relationship between Masumura’s films and the work of Tanizaki. His essay highlights the early, more diabolical work of Tanizaki from 1910 to 1930 and explains that it was these Taisho era writings that most interested Masumura. Lamarre also brings to light the celebrated author’s little-known stint in the film industry during the 1920s and how his love of “moving pictures” lends a cinematic quality to his stories, making them ripe for onscreen adaptation.

Arrow’s release also features a welcome introduction to the film from charming Asian cinema expert Tony Rayns, who provides us with further context regarding the suitability of the project for Masumura. Rayns draws attention to the astonishing fact that the film was entirely studio-shot, a particularly impressive feat given the atmospheric “outdoor” sequences, notably one involving a murderous woodland encounter. Rayns too delves into the source novel, noting that author Tanizaki was rather typical of his generation, having been inspired by the influx of Western literature in the early 20th century from the likes of Edgar Alan Poe and Oscar Wilde. All these extras highlight how perfect the marriage was between Masumura’s filmmaking preferences and Tanizaki’s more sensational stories.

Rounding out the package is an audio commentary from Japanese cinema scholar David Desser, who provides an enthusiastic reading of the film that is quite entertaining. His amusement at the long and lethargic fight scenes is particularly enjoyable. Desser touches on everything from the Yokai lore behind Otsuya’s tattoo to the sexual politics of the film, the focus on which was a hot ticket in Japanese cinema of the 1960s. Most interestingly, Desser discusses the narrative tropes of traditional kabuki theatre that find their way into Irezumi. An early scene on a bridge between Otsuya and Shinsuke has the ambience typical of a kabuki play, while other archetypal kabuki plot points, including vengeful women and lover’s suicide also play a role in the film.

Irezumi marked a significant entry in the erotic and violently charged films that would come to define the latter half of Yasuzo Masumura’s career. Even when putting aside the thematic implications of the work, you’re still left with a devilishly intriguing narrative, an iconic performance from the already legendary Ayako Wakao, and beautiful compositions from a cinematographer at the very top of his game. Irezumi may not be the quintessential Masumura film, but it is, nonetheless, one of the director’s most accomplished and affecting pieces in his long and illustrious career. Arachnophobes, fear not, the spider tattoo dominating Otsuya’s back is unlikely to cause much discomfort…though the conniving woman it’s attached to just might.

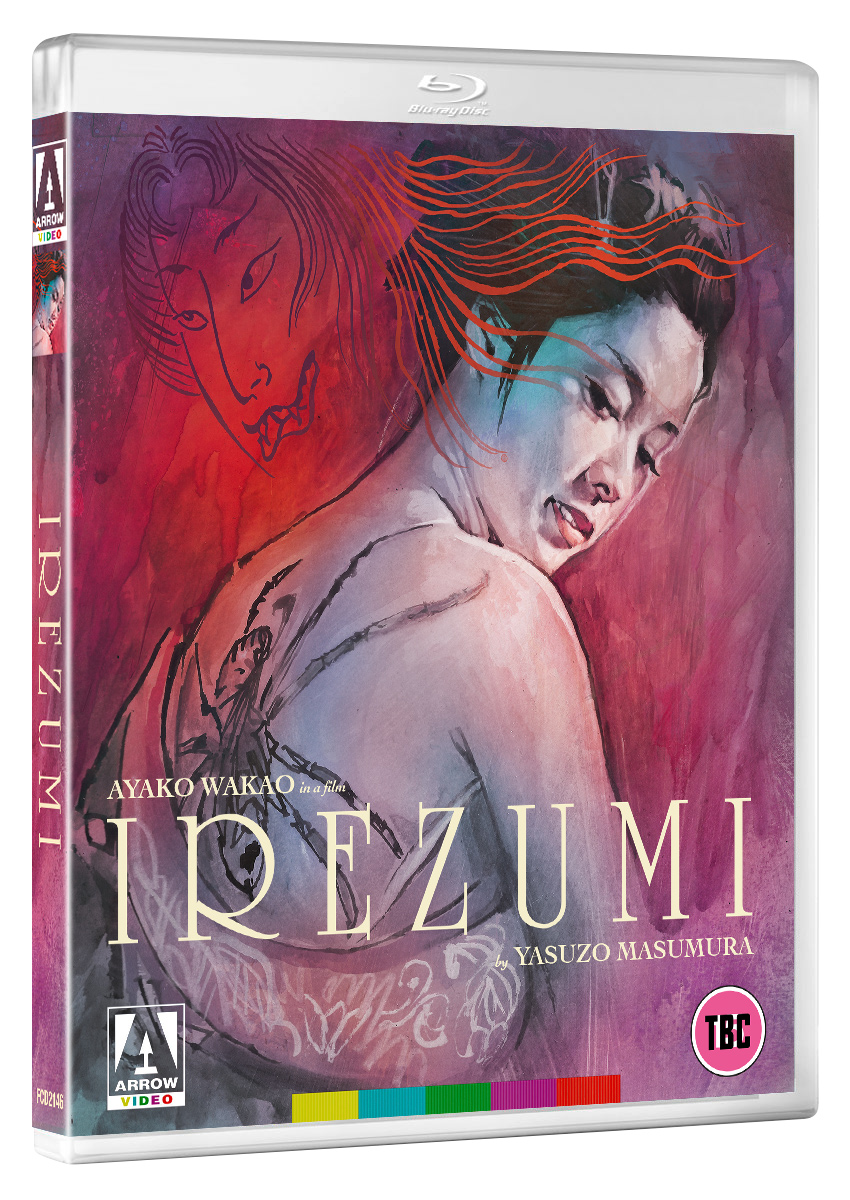

Irezumi is released on UK Blu-ray by Arrow Video.

[ad_2]