[ad_1]

By Andrew Osmond.

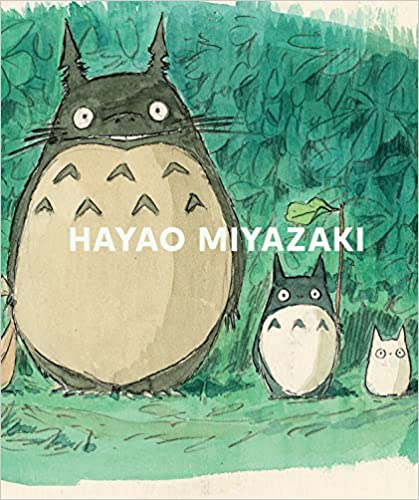

Hayao Miyazaki, published to tie in with the current exhibition about the director at the Academy Museum in Los Angeles, is a whopping big book. It’s a true coffee-table tome, a hefty oversized hardback of 288 pages. For some reason, the exhibition’s website claims it’s only 256 pages, but presumably it had a late growth spurt. It’s not quite the biggest ever print celebration of Miyazaki – that’s the back-breaking deluxe edition of his thousand-page Nausicaa manga. But it’s still mighty imposing.

Of course, the book’s bulk is also a liability. It’s not impossible to carry around, but you’d need a very big bag to accommodate it. The recent Ghibliotheque book, reviewed here, is far more commuter-friendly. Still, the Delmonico book is a lovely object, provided you’re not lugging it round the world.

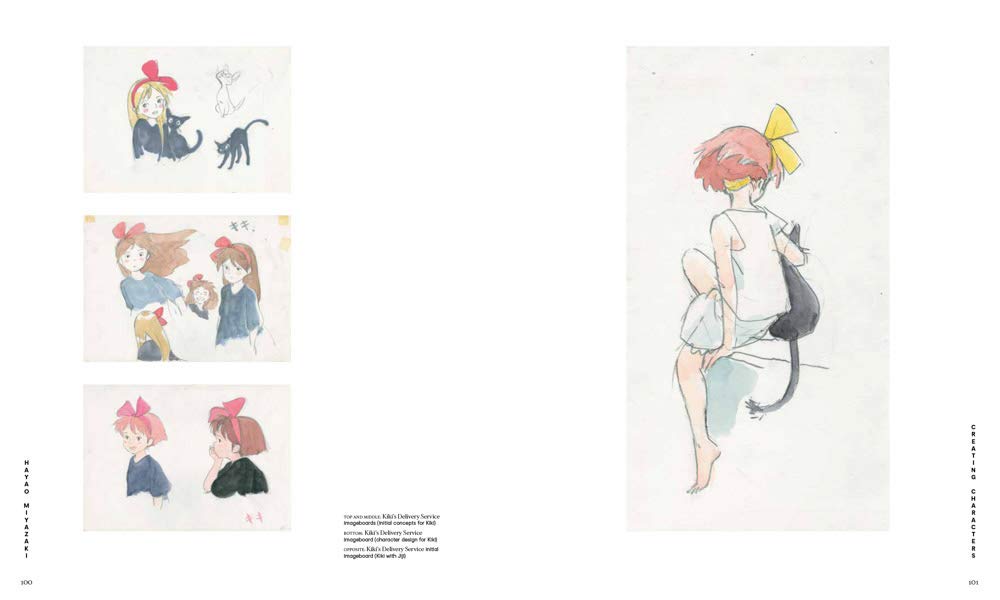

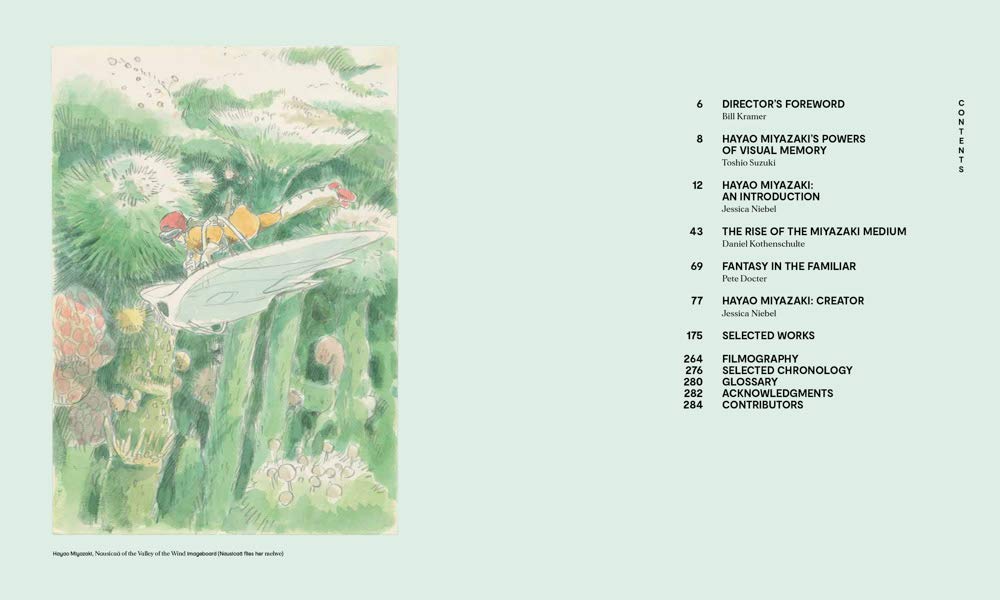

As you’d expect, it’s an art book foremost, printed on high-gloss paper throughout. The pages won’t tear easily. And it consists of the kinds of art that lovers of Miyazaki’s animation would expect. There are a great many stills that reproduce finished images from his films – often background art, so a quick flip of pages takes you from the brilliant emerald of Mononoke’s forest to the meadows of Howl or the rugged ravines of Laputa. But there’s also loads of colourful concept art, plus layouts, imageboards, storyboards, key animation and production and character designs.

Capitalising on the page count, the book gives the pictures room to breathe. They’re mostly large, with usually only one or two on a page. There’s a lot of white space, but the look is pleasingly uncluttered. Certainly there are more than enough pictures that you don’t feel short-changed. But don’t expect the book to cover every part of Miyazaki’s career.

Most of the art is drawn from Miyazaki’s best-known films, starting with Nausicaa and going through to The Wind Rises. It goes a bit wider than that. There are a few examples of Miyazaki’s layout drawings for earlier titles. Specifically, there are two pages on Heidi; one spread with layouts from the likes of Future Boy Conan and Sherlock Hound; and a couple of Cagliostro spreads.

Otherwise, the book is confined to Nausicaa onwards. Moreover, none of Miyazaki’s short films are properly featured – such as those that he made for the Ghibli museum – nor the Ghibli movies that Miyazaki worked on without directing. It would have been great to have some of Miyazaki’s storyboards for Whisper of the Heart, for example, directed by Yoshifumi Kondo. Instead, all such apocrypha is confined to production notes in the final pages, and small posters for the “other” Ghibli features.

A note for hardcore Miyazaki fans, meaning the people for whom one Miyazaki art book is never enough. Viz Media have already published in-depth “Art of” books for each of Miyazaki’s individual films (and two on Nausicaa). I reviewed the Laputa book on this blog. If you’re a maniac like me, and have bought most of these books, or even all of them… then you’ll find you’ll find much of the art familiar. That doesn’t take away the pleasure of the new book’s presentation, and the stills are often larger than they were in the Viz books. But of course it makes the book less essential.

So much for the pictures. How about the text? By art book standards, there’s a generous amount, and a commendable effort to explain Miyazaki’s history and importance to the layperson. But if you’re already familiar with Ghibliotheque, Starting Point, or Susan Napier’s biographical Miyazakiworld, then the text won’t have any stunning revelations. It’s sometimes interesting, but bits of it are also unreliable.

There are two contributions by famous names. Toshio Suzuki writes a short but enjoyable intro, highlighting Miyazaki’s extraordinary visual memory. He doesn’t photograph things, Suzuki says, but he stores them in his mind, and gradually embellishes them with his imagination. Amusingly, Suzuki follows up this tribute by saying Miyazaki’s memory for practical things is terrible,and it has been for decades.

Also, Suzuki drops a rare detail about Miyazaki’s forthcoming film, How Do You Live? One of the film’s characters, Suzuki says, is based on Suzuki himself, recreating everyday interactions between him and Miyazaki. But there’s a catch. The “Suzuki” character appears to be a baddie, and he’s not even human. “I was impressed as well as dumbfounded,” Suzuki writes.

There’s a four-page appreciation of Miyazaki by Pixar’s Peter Docter – director of Monsters Inc, Up, Inside Out and Soul, and now the studio’s Chief Creative Officer. Previously, John Lasseter would have been praising Miyazaki on Pixar’s behalf, but that wouldn’t feel right these days.

In any case, Docter’s piece is generous and interesting. He argues that the magic of Miyazaki’s films lies in their combo of wondrous fantasy and believably grounded, carefully observed details. A similar argument was made in a BBC video by Ghibliotheque’s Michael Leader, though he extends it to Ghibli in general. I’m not sure that it captures the whole essence of Miyazaki or Ghibli, but the combo is indeed vital for their works.

Docter writes lyrically, “In a world where most of us can’t sit for longer than a few seconds without pulling out our phones, Miyazaki’s films invite us to feel the breeze as it blows through a field, dream along with a young girl as she watches a cloud drift by, or wait at a bus stop with two sisters on a rainy evening.”

On a gossipy note, Docter mentions that, when he talked to Miyazaki, the animation legend appeared never to have heard of either Friz Freleng or Chuck Jones! It’s very surprising. Miyazaki may famously disdain anime but he’s usually well up on world animation. Perhaps he finds Bugs Bunny unwatchably vulgar? However, Docter allows the names might have got lost in translation during their chat.

Much of the book’s other text is by Jessica Niebel, curator of the Miyazaki exhibition at the Academy Museum. She creates a good portrait of Miyazaki, whom she met while setting up the event. Her comments are insightful; here she is, for example, describing Miyazaki’s ethos. “Typically, his protagonists leave home and are forced to fend for themselves… In the end, they find balance through connection with their original state of being and the understanding that humankind is an integral part of the universe… Children are closer to such an existence than adults.”

On a more personal level, Niebel writes fondly of her first encounter with Miyazaki’s work. It was his art for the Takahata-directed series Heidi, which Niebel saw as a child in Germany. “How excited was I when the show came on and I could lose myself, for roughly 25 minutes, in Heidi’s world. For hours after, I’d be outside on my swing, trying to fly high enough to jump on a fluffy cloud, to see the world from above – just like Heidi in the title sequence.”

Most of the facts and quotes in Niebel’s writing come from other English sources, especially the Starting Point and Turning Point collections. However, there are a few useful new titbits from Niebel’s own interviews with Ghibli staff. For example, we learn that when Miyazaki considers famous actors for voice roles in his films, he doesn’t audition them because it’s too hard to set up. Rather, he listens to samples of those actors’ current work.

One substantial slip: discussing the end of Spirited Away, Niebel quotes the last lines of the dubbed version, commenting, “Miyazaki finds words of encouragement to end his film.” However, those lines were added in the dubbed version, and have no equivalent in Miyazaki’s original.

The book’s other main writer is Daniel Kothenschulte, an author, curator and lecturer on film and art history. He has a 20-page essay in the book, contextualising Miyazaki and his films. Some of it is sound and useful, but the critical passages read awkwardly, and the history isn’t always sound. There’s a warning flag early on where Kothenschulte uncritically claims that Japan’s so-called “Matsumoto fragment” – a three-second scrap of animation – dates from 1907, even though its precise date is a far more nuanced discussion.

Other oddities in Kothenschulte’s section include his claim that a 1957 Russian cartoon film of The Snow Queen, which influenced the young Miyazaki, included an airplane – not in the version that I saw! Later, the essay quotes Miyazaki’s comments about Lupin, taken from Starting Point, but they’re so abbreviated that Miyazaki’s point is reversed. Kothenschulte gives the impression that Miyazaki’s vision of Lupin was a trendily apathetic hero. That’s the opposite of what Miyazaki said he wanted.

Takahata’s Grave of the Fireflies is described as “far more popular” than Heidi, which sounds weird even if Kothenschulte is thinking of territories where Heidi wasn’t released! The Nausicaa film is said to have been distributed by Toei Animation; it was actually distributed by the wider Toei company. And while I love the Nausicaa manga, I almost choked at a claim that Miyazaki’s strip was, “Perhaps the most successful manga in history” (sic).

One further issue with both Niebel’s and Kothenschulte’s accounts is how they paint a suspiciously rosy picture of Miyazaki’s relationship with his Ghibli staff. “The staff couldn’t be more appreciative of being able to work with the master so closely and over such long periods of time,” Niebel claims. Kotenschulte writes of Miyazaki determining every detail of his films, as if the artists in his “master workshop” added nothing that Miyazaki didn’t originate himself. Sakuga fans have been working hard to debunk that magic idea.

Moreover, the recent Ghibliotheque book gently undermined the notion of Miyazaki’s films as utopias for animators. For more, see this blog’s review. From what I’ve heard, there’s a book coming up in the near future that will examine rigorously how Miyazaki’s films are made. Watch this space!

Of course, this isn’t to question Miyazaki’s genius, or to suggest that anyone else could have created Totoro, or Ponyo, or Nausicaa of the Valley of Wind. But when you leaf through DelMonico’s massive celebration of Miyazaki, just remember… Miyazaki didn’t create all of those beautiful pictures.

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films.

[ad_2]