[ad_1]

By Andrew Osmond.

Last year saw Ghibliotheque: The Unofficial Guide to the Movies of Studio Ghibli, a book by the hosts of the popular Ghibliotheque podcast, which I reviewed here. Now, authors Michael Leader and Jake Cunningham have ventured beyond Ghibli with The Ghibliotheque Anime Movie Guide.

Their podcast went past Ghibli long ago, with mini-seasons on the works of Satoshi Kon, Mamoru Hosoda, Cartoon Saloon, Henry Selick and Studio Laika. Ghibli’s films were covered in the first book, so this “sequel” chooses thirty non-Ghibli anime films to discuss. For podcast followers, it’s logical, though other buyers may be confused by a book with “Ghibli” in the name that doesn’t review Ghibli films. Maybe it could have been subtitled Beyond Ghibli?

Of course, the internet is full of anime film lists. Leader took part in a wide-ranging one for Sight & Sound, with a high quotient of vintage and underseen titles. I was involved too, and argued for a conservative selection of easy-access gateway titles, but the other writers wanted something more adventurous. If you like that list, then you’ll love Mike Toole’s epic “alternative” best anime list at Anime News Network.

Of course, The Ghibliotheque Anime Movie Guide is distinguished because it’s Ghibliotheque’s hosts on the films, like Mark Kermode on horror flicks or Peter Biskind on 1970s “New Hollywood.” As well as excluding Ghibli films, the writers put in another rule; only one film per director. While they curse this at times, especially when it comes to choosing a Satoshi Kon film (they plump for Millennium Actress), it makes the book feel more rounded and the inclusions less predictable.

The book’s format largely duplicates its predecessor. As before, Leader writes the background info for each title, and Cunningham reviews it. The new book also keeps a great idea from the first, having page-size Japanese posters of each of the featured anime. The one for Ghost in the Shell showed the naked, “plugged in” image of Kusanagi (not from the film) and mixes the Japanese text with the shameless English tag, “Who slips into my body and whispers to my ghost?” The Roujin Z poster, meanwhile, eschews robot beds or OAPs, plumping for the cute Haruko on her bike.

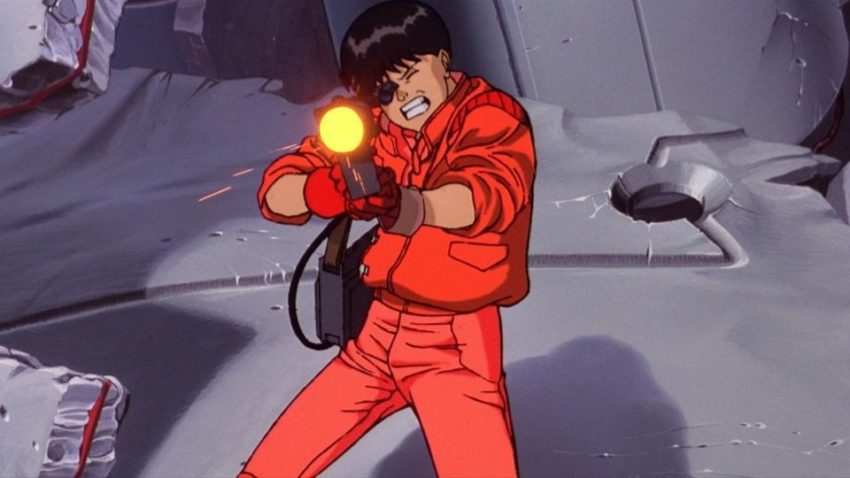

However, the fact that the new book is almost the same size as its predecessor, while covering six more anime titles, makes a difference. The chapters are shorter, often a title spread followed by four more pages (plus a few twos and sixes). The pictures can’t be as expansive; I missed how the images in the first book often covered a full two pages, or one and a half. Notably, the book’s hardback covers feel slightly rough and prickly, which may be deliberate – the cover image is based on Akira, all teen truculence. But I preferred the lovely woody smoothness of the original’s Totoro cover.

The book’s less surprising picks include those three export pillars of action anime, Akira, Ghost in the Shell and Ninja Scroll. Despite the one film per director rule, Katsuhiro Otomo’s impact is also felt in the Roujin Z and Metropolis entries, and Mamoru Oshii’s on Jin-roh. Makoto Shinkai is represented with Your Name, Naoko Yamada with A Silent Voice and Mamoru Hosoda with Belle. Hiroyuki Imaishi, best known for series like Gurren Lagann and Kill la Kill, gets in with Promare. I can hardly complain about the Masaaki Yuasa selection being his brilliant breakout Mind Game; sorry, Night is Short lovers.

Keiichi Hara is included through Miss Hokusai, though the text acknowledges the massive acclaim in Japan for Hara’s 2001 anarchic comedy, The Adult Empire Strikes Back. That film, though, is almost completely unavailable in a legal English copy, barring occasional one-off screenings. It’s also tied to a huge franchise, Crayon shin-chan, which never clicked in the West, though the film’s still funny for newbies. The book does let some other spinoffs through: Miyazaki’s Lupin film Castle of Cagliostro, the Cowboy Bebop film, and the first Eva “rebuild” film, You Are (Not) Alone, which offers newbies a beginning of the Eva story, if not an end.

The titles are arranged in historical order. The Eva film is wrongly dated 2015 on the page, but rightly placed in the book, between 2006’s Tekkonkinkreet and 2009’s Redline. As with the first book, the chronological ordering allows for various narrative threads, such as Western perceptions of anime being reshaped by successive titles: Akira, Ghost in the Shell, Cowboy Bebop. The Akira entry has a lovely nod to the BBC 1994 “Manga” documentary hosted by Jonathan Ross, which was made when Otomo was the big name in anime and Hayao Miyazaki was “Who?”

The text is very sound, though to play nitpicker, the hero Jubei in Ninja Scroll is not a ninja himself, he’s a straightforward swordsman. A caption on page 18 misleadingly suggests that Hayao Miyazaki animated the standout giant fish battle in The Little Norse Prince, whereas that was Yasuo Otsuka. The Wings of Honneamise chapter refers to “Ryuichi Sakamoto’s enchanting score,” which again is a bit misleading, given there were three other people on it.

Cunningham’s reviews are complimentary – these are recommendations, after all – but frank. In the case of Hosoda’s Belle, he starts by claiming this is a superior “Beauty and the Beast” film to either the Disney cartoon or the Jean Cocteau classic. But then he goes on to blast most of Hosoda’s earlier signature films for the clash between their “high-concept ideas” and the characters’ emotional experiences. I found this argument too compressed to be convincing, but then Cunningham thinks Belle escapes the problem anyway.

Like any reader of a review book, I thought some of the judgments sold films short. Re Little Norse Prince, it’s said that “a shift in character focus leads to a slightly meandering second act,” which I think misses the point of a clever structural trick, showing much about the storytelling of Isao Takahata. Again with Cagliostro, Cunningham writes “there is a clear binary choice” between the film’s simple heroes and villains. That overlooks some of the film’s subtler currents – Lupin, after all, is far less innocent than Clarisse, who herself carries the shadows of her family heritage.

I wasn’t convinced to try some of the book’s picks again, such as Redline and Metropolis – and on the subject of the latter, the book underplays the huge amount of retro-baggage involved in placing Osamu Tezuka’s star characters from the 1950s into a CG-heavy film in 2001. More broadly, the book’s newbie-friendly approach often skates over the intricacies of how films relate to their non-film precursors. You could explain a lot more about Cagliostro and Promare on these lines, and the films of Evangelion and Cowboy Bebop.

Perhaps a regular reader of this blog is not be an ideal reader for the book. Conversely, it would be interesting to know how many of the podcast’s listeners who know only Ghibli anime would be tempted by Ninja Scroll or Akira. The book itself offers the suggestion on the last pages that the “next Miyazaki” may be a non-anime studio, Cartoon Saloon in Ireland, which made Wolfwalkers and The Breadwinner. Does a grounding in Ghibli prepare people for other kinds of anime, or for Ghibli-esque movies that may not be anime? That’d be a good question for a future Ghibliotheque podcast.

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films. The Ghibliotheque Anime Movie Guide is out now.

[ad_2]