[ad_1]

By Andrew Osmond.

The Ghibliotheque podcast started in 2018, and soon became an institution. It offered a journey through the films of Studio Ghibli, presented by Michael Leader and Jake Cunningham. Leader was a paid-up Ghibli fan already – you can see his video overview of the studio here, made for the BBC’s “Inside Stories” series. Cunningham hadn’t seen any of Ghibli’s films at the outset, and the original podcasts were balanced between Leader’s contextualisations and Cunningham’s first-time reactions.

After working through Ghibli’s oeuvre, the podcast moved on, covering Satoshi Kon and the films of Ireland’s Cartoon Saloon (Wolfwalkers). But it frequently revisits Ghibli, interviewing numerous big-name fans of the studio, including Jonathan Ross, Rebecca Sugar (Steven Universe) and Aardman’s co-founder Peter Lord. It’s also snagged interviews with Toshio Suzuki, Goro Miyazaki, Steve Alpert and Michael Dudok de Wit. Leader and Cunningham even podcasted from Japan, where they visited the Ghibli Museum and Studio Ponoc.

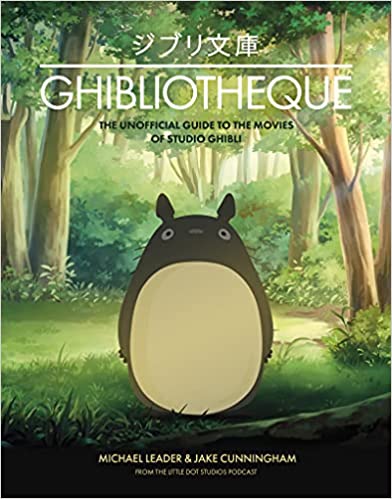

You can hear the podcast’s old and new episodes on Apple (which has exclusive bonus segments), acast and Spotify. Now Leader and Cunningham have distilled their Ghibli thoughts and findings into a book, Ghibliotheque: The Unofficial Guide to the Movies of Studio Ghibli. It’s one of the most attractive anime books I’ve seen, a sturdy oversized hardback wrapped in the soothing colours of Totoro. It’s smaller than the Ghibli art books, but it’s portable while still feeling very solid; you can rap your knuckles on it satisfyingly. While there’ll be a Kindle version, that will inevitably lose that charm.

It’s also packed with colour pictures – at least one per page, with plenty of full-page and double-page stills. Admittedly, many are familiar to Ghibli fans, and there’s little in the way of concept art, model sheets and the like. But there are still some very good touches. For example, there’s a page-sized poster for nearly every Ghibli film (the exception, for whatever reason, is From Up on Poppy Hill).

There are also photos from the Ghibli Museum, including a lovely double-page spread of the studio’s gorgeous artworks pinned blithely to a wall. There are helpful photos of Ghibli’s staff, and of interesting moments – a live Paris concert performance of Totoro, and the “real” glider made by Nausicaa fans. There are glimpses of the authors themselves, geeking out in Japan – for instance, re-enacting a scene from Whisper of the Heart, or brandishing an Only Yesterday poster they found in the otaku mall of Nakano Broadway.

The book confines itself to Ghibli’s features. There’s a section on the TV film Ocean Waves, but only passing references to the studio’s museum shorts and On Your Mark; to proto-Ghibli films like The Little Norse Prince and Castle of Cagliostro; and to Ghibli’s producer role in the Polygon-animated series, Ronja, the Robber’s Daughter, directed by Goro Miyazaki.

The book starts with Nausicaa, with the mandatory disclaimer that it’s not actually a Ghibli film. Fair enough; Nausicaa’s been bundled with the Ghibli canon for decades. It’s a slight pity, though, that the chapter doesn’t namecheck the actual studio that made the film, the eternally unsung TopCraft. From there, the book rattles through the decades all the way to last year’s Earwig and the Witch.

One thing which raises my eyebrows is that the book includes The Red Turtle as part of the Ghibli canon, whereas I’d put it in the canon of its own esteemed creator, Michael Dudok de Wit. As outlined on this blog, Ghibli co-produced the film, but the studio’s creative involvement was limited to a few informal suggestions, and they were really suggestions. The whole point of the exercise was to have a film by Dudok de Wit.

Moreover, Red Turtle was animated thousands of miles away from Ghibli, and involved none of its artists. The book asserts that, “Make no mistake, The Red Turtle is a Studio Ghibli film,” with “clear Ghibli genealogy.” But that genealogy is far more obvious in Studio Ponoc’s Mary and the Witch’s Flower, which involved loads of Ghibli artists. Mary doesn’t get a section in the book, though it’s discussed in the entry on When Marnie Was There. Of course, Ghibli would never give so many pictures to a book which featured a rival studio’s film!

But if that suggests the book’s commentary might be steered by Ghibli, that’s absolutely not the case. The opinions in the book are plainly the authors’ own, and forthright to a degree that’s startling. For example, there’s a clear itemising of all the times Ghibli seems to have crushed and frustrated the work of artists who aren’t Miyazaki or Takahata, artists who might have made Ghibli’s future far more secure than it is now.

The most famous of those artists is Mamoru Hosoda. His experience as a young director of getting thrown off Howl’s Moving Castle is highlighted in the relevant chapter. But the book points out a precedent – Sunao Katabuchi, future director of In This Corner of the World, was similarly turfed off directing Kiki’s Delivery Service. I knew he was on the film, but not that he was meant to be Kiki’s director. The Ghibliotheque book’s references cite an interview in which this gossip is suggested but not really confirmed; one has to dig a little deeper to find a Japanese source that supports it [I pressed the All the Anime Bat Signal, and Jonathan Clements dug it up for me].

The book also points up Miyazaki’s throwing callous barbs at another fledgling director, Hiromasa Yonebayashi, during the making of Arrietty. Then there are the trials of Yoshiaki Nishimura, who worked as producer on Princess Kaguya. It was Nishimura, the book notes, who had to carry the can for the film in Takahata’s place, telling the press that Kaguya would miss its release date. Not long after, Nishimura quit Ghibli to found Studio Ponoc, where Yonebayashi went to direct Mary.

The book stops short of joining the dots between Hosoda, Katabuchi, Yonebayashi and Nishimura, but then it doesn’t have to. You could add a comment by animator Aya Suzuki to this blog: “Between Japanese animators I know, Ghibli doesn’t have the best reputation, not because it’s a bad studio but it can be quite disheartening to an artist.” Miyazaki himself wrote of his youthful frustrations as an animator at his first employer, Toei in the 1960s, and how he and his colleagues had to flee the coop. Plus ça change?

As this thread suggests, one pleasure of this book is putting the Ghibli narrative together. Ghibliotheque draws heavily on two recent first-hand accounts, Steve Alpert’s Sharing a House With the Never-Ending Man and Toshio Suzuki’s Mixing Work With Pleasure. Another thread is Ghibli’s relationship with Western markets, from the early infamy of Warriors of the Wind, through the Disney distribution deal in the 1990s, and then Ghibli’s switch from Disney to GKIDS as its American distributor in 2014.

The book notes that the highest-grossing Ghibli film in American cinemas wasn’t Spirited Away, nor Howl, and it certainly wasn’t Mononoke. No, it was Disney’s version of Arrietty! Since then, the book notes, Ghibli films “would receive modest, targeted US theatrical releases by the animation-focused distributor GKIDS, a company more attuned to the Studio’s prestige status… and less concerned with producing a blockbuster.” Excellent stuff, though it’s a shame the book doesn’t mention Arrietty’s different dub in Britain. That had a young actor called Tom Holland, who’s now in some films about spiders.

Ghibliotheque is divided into separate chapters on the 24 films, though some, understandably, get more space than others. Sensibly, the first part of each chapter sets up the context, followed by a review that covers one or two pages. There isn’t the leisurely discursive analysis of Susan Napier’s Miyazakiworld or Christopher Bolton’s Interpreting Anime. The reviews are closer to long magazine reviews, written in a breezy, informal style. Again, it’s a wise approach, although podcast fans might miss the sense of dialogue and friendly disagreement between the book’s authors. The foreword explains Leader wrote the “history” text, while the reviews are by Cunningham.

Those reviews have no huge shocks – no claim that Spirited Away or Fireflies is grossly overrated, or that Poppy Hill is Ghibi’s one true masterpiece. The book might ruffle a few feathers with the claim that Tales from Earthsea isn’t that bad, deserving a passing grade. The review of The Cat Returns sounds more disappointed, though the writer doesn’t specify which film he thinks is better (or less bad). If you do want to see Cunningham’s rankings and star ratings, they’re given on the letterboxd website, which reveals Cunningham ranks Earthsea above not only Cat Returns, but also Howl and Ocean Waves. (Leader disagrees.)

The book’s homoerotic take on Ocean Waves, perhaps Ghibli’s least-discussed film, is especially interesting, prompting me to rewatch the film. I can go along with some of the argument, which highlights details I’d never registered, though I’m not convinced by its conclusion. The book claims Ocean Waves is a should-be-gay romance that loses its nerve; for me, the film acknowledges overlapping attractions and teen feelings that may only resolve when perspectives change over time and distance. I was also surprised how easy the book goes on When Marnie Was There, which is often criticised on very similar grounds. Of course, these arguments run on – look at the discourse over Pixar’s Luca – and I’ve touched on them in another article.

Of the films by Ghibli’s “main” directors, Howl also gets off lightly for a film that Cunningham rates worse than Earthsea (“Who wants a Hayao Miyazaki film that is just okay?”). Takahata’s Yamadas is described mildly as “testing.” The reviews give most love to the likes of Totoro, Mononoke and Whisper, while Grave of the Fireflies is “an incredible work of art.”

But it would sound weird to speak of loving Fireflies, and that reflects a divide that could be discussed further. It’s the double-bill twin of Fireflies, Totoro, that the book claims is Ghibli, the studio’s quintessence. Totoro is a Miyazaki film, of course. And it’s undeniable that the popular perception of Ghibli, in Japan and abroad, is bound up with one director only, and we don’t mean Takahata.

That isn’t denying the greatness of Fireflies or Kaguya, but acknowledging the lopsided nature of an outfit that so much of the audience sees as “the Miyazaki studio.” At one point, Ghibliotheque suggests lightheartedly that Takahata was the visionary, experimental Lennon to Miyazaki’s populist McCartney. But in terms of public recognition beyond fans and critics, Takahata is nearer Pete Best or Stuart Sutcliffe.

It’s not the only time we’ve had this situation in animation. Earlier, I mentioned Peter Lord, who founded Aardman Animations with David Sproxton. But how many people on the street automatically think of Aardman as “the Nick Park studio”? (Own up if you thought Park directed the Shaun the Sheep movies, for instance.) But the situation with Ghibli is more extreme. In 2013, Miyazaki’s least populist film, The Wind Rises, earned $113 million at Japan’s box-office. Takahata’s Kaguya, released months later, couldn’t get a quarter of that.

The odds seem against Studio Ghibli living any longer than Miyazaki, at least as a maker of animation. And yet Ghibli will outlast Miyazaki, in terms of the “Ghibli genealogy” cited earlier; its DNA has seeped into so many other films. There’s Studio Ponoc and Mary and the Witch’s Flower. There are non-Japanese films like Wolfwalkers (compared by Tomm Moore to Mononoke) and April and the Extraordinary World. There’s also such diverse anime as Okko’s Inn, Patema Inverted, Weathering with You, Children of the Sea, Giovanni’s Island and In This Corner of the World. Each was made by a different studio and a different director in the last decade.

Giovanni’s Island and In This Corner recall Takahata’s work more than Miyazaki’s. So did Mirai by Mamoru Hosoda, the first non-Ghibli anime feature nominated for an Oscar (in 2019). Hosoda confirmed Takahata’s huge influence on his work when I interviewed him for this blog. That’s worth remembering now, as Hosoda cheerfully trash-talks Miyazaki at film festivals.

Another thing to remember; an apocalyptic image in Ghibli’s not-really first film, Nausicaa. The film’s giant insects, the Ohmu, rush for endless miles over land. Finally, they die, only for their bodies to seed a new eco-system which engulfs the world. If that’s Ghibli’s legacy in animation, Miyazaki would approve.

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films. Ghibliotheque: The Unofficial Guide to the Movies of Studio Ghibli is published by Welbeck.

[ad_2]