[ad_1]

By Helen McCarthy.

Rintaro’s 1979 film Galaxy Express 999 travels a very considerable distance, goes faster than you might expect, but skips a number of stations. And the infrastructure still isn’t complete, so some destinations remain unreachable… a bit like Crossrail.

In Japanese rail parlance, both Crossrail and Galaxy Express 999 the movie are limited expresses – trains that stop at fewer stations than other expresses on the same route. They’re faster, but not necessarily more convenient. Travellers might even complain about the timetable: why this station and not that one?

Welcome to the world of the director required to turn a major manga and anime franchise into a coherent, fan-pleasing film before the original story is even approaching completion.

“I slept on it for a few days,” Rintaro said in a 2009 long interview with Yuichiro Oguro for the Plus Madhouse collection. “Since I did Astro Boy, I had thought TV would be enough for me. In the 30-minute frame with an ad break, stories develop quickly – I had been a director in such a uniquely TV world, so I thought I was content with that. To start with, there weren’t many feature-length anime back then.”

When Leiji Matsumoto’s Galaxy Express manga first appeared in Weekly Shonen King late in January 1977, it was, like all weekly manga, subject to cancellation if reader numbers fell. Luckily readers crowded on board Matsumoto’s galaxy-spanning steam train. His Space Pirate Captain Harlock was a major TV hit in spring 1978, and the movie Farewell to Space Battleship Yamato hit the theatrical circuit in July. In September 1978 the Galaxy Express 999 anime TV series commenced airing. The continuing success of both manga and anime led to the premiere of Rintaro’s movie in August 1979.

A film-of-the-series has a timetable problem before it starts. When Rintaro began work on the movie, there were already two and a half years of manga instalments and almost a year of anime episodes available. That had to be condensed into a theatrical slot of around 130 minutes. “Mr Matsumoto came up with a tremendous amount of plot,” admitted Rintaro. “When we did Harlock, we didn’t have enough story, so we added a girl character, but this time, there was no need for that. The volume was such that if we made that into a film, it would be four or five hours long.”

In addition, Galaxy Express 999 was nowhere near the end of the line. The TV series had only just started as film production began. The manga would not finish its run in Weekly Shonen King until 1981. Matsumoto had some major plots twists in mind for both formats and the movie had to be spoiler-free. Rintaro and writer Shiro Ishimori had to make sure that nothing vital to their self-contained story structure was omitted, and to avoid any major changes that might impact the ongoing franchise. Rintaro approached Ishimori himself owing to his love of the writers earlier 1972 work, Promise. “I wanted that same sensibility to depict the relationship between Maetel and Tetsuro. So, I met Mr Ishimori and asked him myself. He had never done animation at that time, so he said: ‘Er… Can I do anime?’ And I said: “Yes. Please do it with that sensibility.’”

Luckily, the format of both manga and anime had the train visit different planets for self-contained adventures along the line. So, the director could cut out all but four planetfalls for his limited-express version of the story so far: Saturn’s moon Titan, Pluto, Heavy Melder and Andromeda. They took the story as far as they could within the manga and anime timeline, omitting many subplots/planetfalls, taking liberal advantage of coincidence and luck as plot devices, but ending with a fan-pleasing battle, beloved character crossovers, and heroic sacrifices to ensure the young hero survives. As adults looking back over four decades, we can choose to be squeamish or amused at a teenage boy winning the respect of seasoned warriors and having two space babes fall in love with him, but to young fans, seeing the picture for the first time amid the senseless surges of adolescent emotion, it made perfect sense.

“I think the works of Leiji Matsumoto are sentimental,” remembered Rintaro. “And if that’s not the right word, then they have a sense of gloominess. An aesthetic of gloominess. I could sense that, talking with Mr Matsumoto. That’s why you cannot do them without sentimentalism in his works. I don’t dislike that, but, when it came to 999, while I was drawing the storyboard, the content became my flesh and blood, and I must have become a bit sentimental myself.”

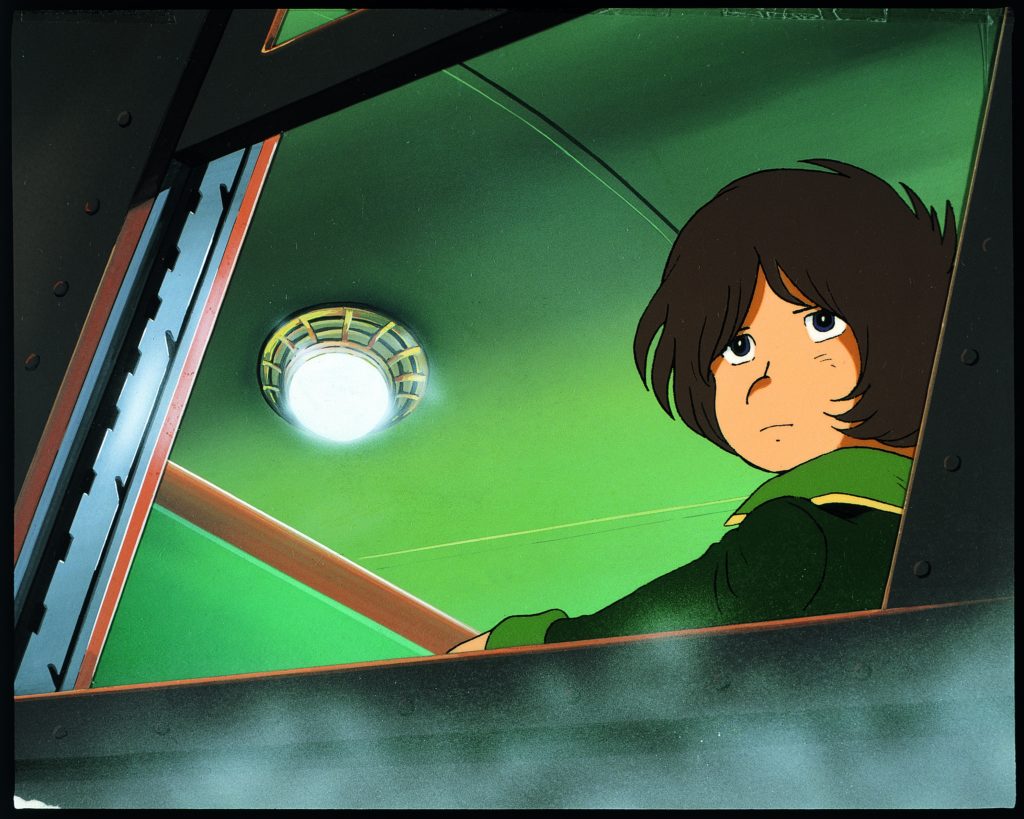

It’s no surprise that, alongside today’s whizzbang technology, the animation is clunky. The surprise for those unfamiliar with either Rintaro or Matsumoto is that its clunkiness comes wrapped in an undeniable grandeur. The grandeur of the conception – a huge, powerful, old school steam engine hauling carriages along a track that miraculously unravels between the stars, through black star-studded space from planet to planet, its staff as inscrutable as the technology itself – originated in the teenage Matsumoto’s own first journey from his home on the island of Kyushu to Tokyo, on just such a mighty steam train, in search of his own destiny. Matsumoto has a gift for wrapping pure cores of human emotion in grand baroque flourishes reminiscent of the operas of Richard Wagner (among his personal favourite music) or the Technicolor hothouse of Mika Ninagawa’s photos and film. And Rintaro never shoots a dull frame.

“There’s a shot toward the end,” says Rintaro, “where there’s a big setting sun, and the train runs towards it, and Tetsuro comes into the foreground. There is no realism whatsoever, but as far as it looks good, that’s enough. I did it because I was confident it was going to make the audience cry. Then Tatsuya Jo’s narration comes in, and the Godiego song starts. The wind blows. What else do you need?”

Rintaro was just seventeen when he got his first job as an in-betweener on the landmark movie Hakujaden. He’s three years younger than Leiji Matsumoto, born just a few days before Matsumoto’s third birthday in January 1941. Like others among the emerging young talent to Toei, he was poached by Matsumoto’s friend Osamu Tezuka for his new studio Mushi Pro.

At 21 he was directing episode 4 of Astro Boy, the 1963 TV series that rewrote the rulebook for Japanese TV animation. He left Mushi Pro in 1971 before it teetered into bankruptcy, and has been a freelancer ever since. In his long career he has always been a meticulous and adventurous student of his craft, constantly seeking to learn and improve. In an interview for SciFi.com he describes the process he calls ‘detachment’ by which he integrated the digital animation and cel painting in his dazzling film of Tezuka’s Metropolis (2001).

All Rintaro’s films and TV series are worth watching, but the Galaxy Express 999 movie has its own particular rewards. On film he can frame the majestic vistas of the mighty steam train in space with more depth, richness and grandeur than is possible for TV animation. In a feature runtime he can exploit the road-trip format with all its wonders and novelties, presenting the hero’s journey in flowing, beautiful sequences that still impress today, without the repetition inherent and often essential in a TV series. Today’s audience may prefer this readily assimilable format, delivering the major character highlights and story beats of the early manga without requiring them to watch multiple TV episodes at a lower film and animation quality.

Matsumoto originally intended this movie to have a sequel, wrapping up the story of the first film but not necessarily tracking the TV series or manga; this was Adieu Galaxy Express 999, also directed by Rintaro and written by Ishimori. It premiered in August 1981. With the exception of one scene, Rintaro and Ishimori created an entirely new story, independent of both manga and TV series. Their approach fitted very well with Matsumoto’s own constantly shifting cycle of character rebirth, reuse and reframing. This sequel found an unexpected champion in the young Mamoru Hosoda, future director of Belle, who went to see it eight times at the cinema, and proclaimed it to have had a “revolutionary” impact on him.

“The appeal of the first film is in the vigour of the filmmaking,” Hosoda wrote, “but in the second film, everything was upgraded: music, art, drawings, and modulated storyboards. The background art and the colour design were more detailed, and I felt it was more realistic. The fact that the space was black was also a key. The space in the first 999 was bluish. Compared to that, there is a clear contrast, which made me feel it was more realistic.

“Those are people who are not happy with Adieu, Galaxy Express, who probably feel that ‘there was no continuity from the first film’. But I didn’t care about that at all. The protagonist of the first and the second film share the same name, Tetsuro, but I think they could be completely different people. The first film was, as it were, ‘a youth story in which a delinquent boy grows up through the journey’, but the second one was, from beginning to the end, about the making of a young revolutionary.”

The third movie, released in 1998, was entitled The Galaxy Express 999: the Eternal Fantasy. It’s got glossier animation, but that doesn’t make it a better movie. The sheer emotional weight and visual grandeur of Rintaro’s version is as powerful as all those atavistic images of the age of steam. The engine’s about to pull away; you still have time to get on board.

“The first print was shown at Toei’s studio screening room,” remembers Rintaro. “When the film was finished, every single Toei employee stood up and applauded. Even now, people say: ‘It is impossible that you get a standing ovation’. So, it was a good feeling.”

Galaxy Express 999 is screening at this year’s Scotland Loves Anime. Helen McCarthy is the co-editor of Leiji Matsumoto: Essays on the Manga and Anime Legend.

[ad_2]