[ad_1]

Note: ANN is excited to publish a recently discovered interview between Mamoru Oshii and our reporter, Richard Eisenbeis, from 2017.

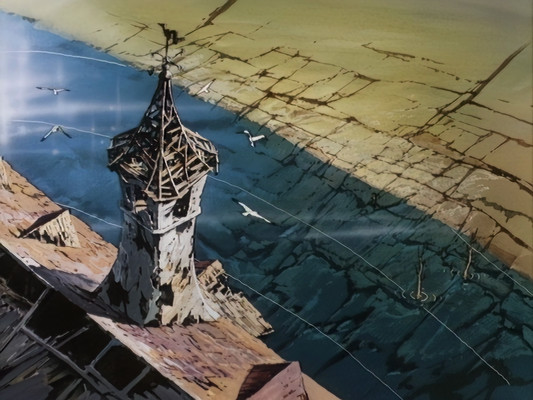

Before Patlabor and Ghost in the Shell, renowned director Mamoru Oshii wrote and directed Beautiful Dreamer—a film that takes the long-running gag anime Urusei Yatsura and turns it into a surreal masterpiece. I was able to sit down with him and have an in-depth talk about the film.

You have many famous works. Obviously, in America, Ghost in the Shell is the most famous, but another one is one that was popular when I was a kid: Urusei Yatsura 2: Beautiful Dreamer. That was your first…? Your second…?

That was my second movie.

Only You was your first, wasn’t it? Looking back on Beautiful Dreamer, what do you think about it now?

Well, that I was very young (laughs). I used to be a rather dreamy kid. I’d fantasize a lot and think about different things from the reality I was in. I was the kind of kid who didn’t really “believe in reality.”

Even when talking, I’d think things like, “Is this person real?” or “I think this has happened before.” Like, “I’ve met someone like this before.” I’d wonder if the same person was pretending to be someone else, if everyone was working together to try to deceive me. I was a huge daydreamer. That’s the kind of kid I was, so I was always spaced out.

And I’d sleep a lot. I love sleeping.

(Laughs) Then is the movie about your dreams?

(Laughs) That’s not what I mean. I had that sort of disposition as a child and I ended making Beautiful Dreamer with that. So it’s not like there was a specific theme.

I wanted to portray that reality is a strange thing. That and structural curiosity. It’s about expression. There’s the genre of metafiction—the awareness within fiction that it is fiction. Fiction within fiction or fiction that exists in parallel with fiction on a different dimension… That’s the genre called metafiction and at the time I was very interested in it.

So, I wanted to make a movie that has the structure of metafiction. This is why it’s structured very logically. It’s pretty much structured purely by logic. On the other hand, it’s also very thin in its theme.

If there is one, I guess it’s the sort of feeling towards reality that I had, the sort of delusion that “everyone’s working to deceive me.” Also, a sort of “wish for ruin.” I still have that sort of wish for ruin. Even the game I’m currently playing takes place in a ruined world.

I love post-apocalyptic games, games that take place after a nuclear war. I’m currently playing a game where you have to survive in a wasteland. That sort of desire has stuck with me since childhood.

The setting is a kind of “Oshii world,” isn’t it? (Laughs)

It’s the perfect world for me. It’s like my dreams come true, I mean, it’s a ruined world after a nuclear war, violence is everywhere, and you have a partner, a dog that will never betray you, and you run around with your dog while carrying a rifle… It’s the world I dreamed of.

Indeed. Beautiful Dreamer is very different compared to the rest of the Urusei Yatsura series.

(Laughs) They’re completely different.

I don’t think that’s a bad thing. In the film, things from the Urusei Yatsura series and things like Urashima Taro and [Japanese fairytale creature] the Baku all come together into one story. Was that difficult?

Building the structure for the whole thing logically was a very enjoyable task in and of itself. But, with movies, that alone doesn’t make the movie work. You have to figure out how to make the characters appealing.

This is actually where I really struggled. The protagonist, the girl Lum, was very hard to handle. Beautiful Dreamer isn’t actually “her” movie.

I got a lot of criticism for that at the time. Especially from fans of the series. They’d say, “Lum isn’t doing anything. She’s not playing a big role.” I had to make the movie that way.

Beautiful Dreamer may have had some problems as an entertainment piece, because I prioritized the structure over the characters. In that way, it’s a kind of movie that a producer normally wouldn’t allow.

In animation in particular, how “appealing” the characters are is the most important. Well, in Hollywood movies, too. The characters come first and the story is secondary.

Then you have the worldview. That’s the order of importance.

I made Beautiful Dreamer in reverse. You have the world—this world with a special structure—then you have the story, and the characters come last.

Thinking about the movie in and of itself, I still don’t think this was the wrong decision. It was a spinoff of a long-established series—which is why Beautiful Dreamer was green-lit in the first place. The characters were already established.

So what happens if you try that with a standalone ninety-minute movie? That was Angel’s Egg. I made that movie the same way. But the characters were all original, characters you’d never seen before. As a result, you can’t empathize with the characters. You simply can’t.

A minority of film lovers can appreciate it, but normal viewers just don’t know what kind of movie it is. If you are aiming for entertainment, the standard way of making anime is correct: first you have the characters, then the story, and finally the worldview.

But if you stand on the side of filmmaking, it all becomes backwards. That’s the case of a series spinoff. The characters are already established and the viewers already know them. For a movie like that, it works.

However, if you attempt to do the same thing when you are making a movie starting from scratch, the audience gets confused and you end up with something nobody understands. I admit I didn’t truly consider that at the time. I was pure momentum. I was full of myself (laughs).

So, to be young means to explore, which also means to take risks—and as a result, I wasn’t offered any jobs for a while.

That’s something that tends to happen often with sequels, too. Specifically, this was the case with Patlabor. With Patlabor, the first and second movies are quite different from each other. The second movie was made with the focus on the structure because the characters were already established, while the first movie was focusing on the characters.

That’s actually also true with Ghost in the Shell and its sequel, Innocence. The characters are pretty much established in the first movie, so the second movie focuses on the worldview.

We can say that Ghost in the Shell is a movie centering upon Motoko Kusanagi, but in Innocence, she doesn’t actually show up. Just her shadow does.

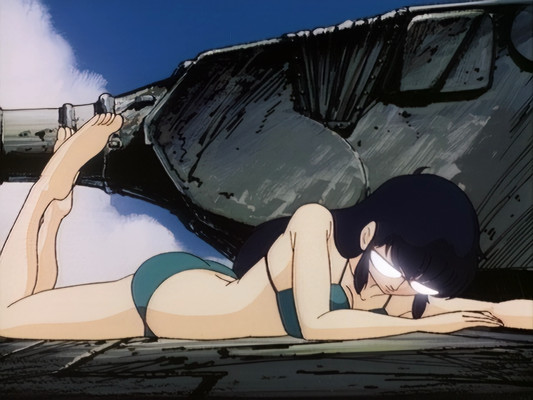

In the West, people think of your style as “visual storytelling.” The best example is this shot in Beautiful Dreamer—the shot that introduces Lum.

From this shot, you can understand so much about her. For example, you can tell that she can fly, but it doesn’t actually show her flying. That’s very interesting. Also, they’re extremely high up, but she isn’t scared. She seems almost invincible. And she doesn’t understand that [the hanging man] is in danger. She’s smiling. And of course, she’s beautiful—and she’s wearing a school uniform, so you know she’s a student… And finally, you can see she has horns. So you can understand why: She isn’t human.

All this from one single shot!

Obviously, as a child, I didn’t understand all of this right away, but there was a lot I did get subconsciously from this one shot. I believe this scene is a very “Mamoru Oshii-esque” scene.

That scene was, for me, a very “gratifying” scene. I remember it very well. I put together the storyboard and it’s a cut that is part of the movie’s legacy. You’re right, there is a lot of meaning in it.

The biggest thing is that she’s standing on the barrel of a tank. Basically, she’s in what we would recognize as a dangerous situation but she is completely unaware of it. She’s an innocent little girl. By innocent, I mean she’s sweet, and cute, and pure.

She’s also ignorant of the situation she’s in. She doesn’t understand human relations. In Japanese, she’s a “troublesome girl.”

Yes, she is. (Laughs) Also, she doesn’t help.

She doesn’t do anything—or rather she does nothing but cause trouble. It makes you wonder why she’s so loved. So, this “troublesome girl” is the main theme of Beautiful Dreamer. But [Ataru] can’t leave [Lum]. Even after he wakes up, he can’t leave her. He’s a womanizer who likes all sorts of women, but he just can’t leave her.

In a way, it’s a movie that’s made up of “wishes.” It’s made up of different people’s desires. That’s why it’s an iconic introduction scene.

So, who appears in what way and where [is important]—like having [Lum] float down on the barrel of a tank sticking into the air… And, after that, she suddenly becomes a danger—because she has her electric blast.

In that way, it’s also a gratifying scene for me, since the only proof that she’s not human is her horns. This is because she’s wearing a school uniform. When I was making this movie, the first thing I decided was that, “she’s going to wear a school uniform.” Usually, she’s wearing her bikini: the one with the tiger stripes.

Of course.

However, by keeping her in the uniform, it’s kind of—how would you put it—I tried to keep a lot of things on the inside. I tried to make her look like a normal girl as much as possible. If she was going to play a huge role, maybe the bikini would have been fine.

Well, that’s one of Lum’s defining attributes in Japan.

A girl’s uniform, the sailor uniform, is a very inhibiting uniform. Because it’s supposed to be a man’s uniform. And since it’s a uniform originally devised for a sailor, the clothes actually inhibit her gender/sexuality. That’s why guys tend to like them. I don’t, though (laughs).

That’s why it’s important that [Lum] wears her uniform almost through the entirety of the film—at least to me.

In a way, she’s being inhibited. Who’s inhibiting her? The wishes of the men around her. They wish to suppress her. To put a leash on her and inhibit her in a way with her uniform. To treat her like an inhibited being. And in the end, it’s destroyed.

That’s also in there.

Tanks also show up every now and then. The reason tanks show up a lot is partly because I’m a tank maniac and I know a lot about tanks. But it’s also because they’re a kind of emotion, a contained emotion. The “male principle.”

Tanks are very masculine objects, no matter how you look at them. The male desire for larger genitalia. Tanks are essentially male genitalia. And then she floats down on one. She’s a very feminine, sexual character, but by having her wear her uniform, it’s like inhibiting all of that.

In that instant, she’s essentially no longer a human character, but an “object.” She’s treated as an “object.” In Japan they have the saying, “placed on the family altar.” Basically it means, “treasured but not allowed to do anything.”

I did that intentionally as a director, but apparently this triggered a reaction in the audience at unconscious level. That’s why most fans ended up rejecting the movie. “We want to see her more unrestrained and flying around.” [and in response to that, I’m saying] “This world is made of the male principle. She’s merely standing on the male principle.” That’s what I wanted the very first scene to symbolize. That’s why there’s a tank in the classroom.

I was saying, “This is a place ruled by the male principle.” And you never know when the tank will [break through the floor and] fall.

In that way, it’s a movie that’s expressed by symbolic scenes and focusing on the structure. So for people interested in “revealing the logic” I believe it was a very interesting movie. But for people who just wanted to be entertained, it probably turned out as a rather cumbersome movie.

However, if we look back on it now, the reason this movie has survived and it is still being watched today, lies in it being a very symbolic and structural work.

I believe a filmmaker should always be considering two factors when doing their job. The first is how a movie will be received upon its release. The second is how that very same movie is going to be considered ten or twenty years later. Even if a movie is very popular when it comes out and millions of people go to watch it, it might be completely forgotten just a year later. Most movies that are being made today tend to follow this fate.

I hate that. Of course I’d like to have both. But since “this and that” is not easy to achieve, it usually ends up “this or that.”

If you ask me where my priorities are, I say that I’d prefer a movie that survives ten years. Even if sometimes it means having a hard time as a director.

(Laughs) Indeed.

Otherwise, I don’t feel the motivation to spend an entire year or two to create a single movie. I want some kind of universality somewhere. The product of an age lives in its age, but I’d like my movies to live on with the people who lived through the same age.

I love being told that someone saw my movie when they were young and still love it to this day. If that person were to die, [the movie] would probably continue to age along with me and other viewers from that same time period. But if we were to die, it probably wouldn’t remain.

I’m fine with that. But at the very least, I’d like my movie to show on a screen somewhere and have someone watch it.

That’s the best thing for a movie director. You can’t buy that with money. You can’t exchange that for money or fame.

The greatest thing for a director is to have someone somewhere see their movie even now. And when they tell me, “it was a good movie!” this makes me extremely happy.

[ad_2]