[ad_1]

Last week, I started talking about the design of Dungeons & Dragons: Adventures in the Forgotten Realms. Today, I continue that story, talking about how all the various components got created and introducing you to the Set Design team. I have a lot to talk about, so let’s get to it.

Let’s begin by introducing the Set Design team. I’m having Jules Robins, the set design lead, talk about himself and each member of his team.

Click below to meet the Adventures in the Forgotten Realms Set Design team.

-

Meet the Set Design team

-

Jules Robins – In my six years at Wizards, I’ve done a lot of design work on a wide range of challenging spaces, from Battlebond and digital games to serving as the red mage on the Council of Colors, and I even led vision design for Ultimate Masters and set design for Commander Legends.

But Adventures in the Forgotten Realms brought a whole new host of challenges: the broader audience of a main Magic set, the pressures of more competition, and most of all, the challenge of capturing the essence of another property in Magic cards. It was a monumental task, and there’s no way we could’ve pulled it off without contributions from a ton of people, so I have a long list of introductions today. (The Adventures in the Forgotten Realms Set Design team went through numerous incarnations.)

Andrew Veen – Andrew and I worked together on Guilds of Ravnica, I played in his Tomb of Annihilation campaign, and here we finally got our chance at leading a main set: his first vision design lead of the sort, and my first for set design. We both worked on each other’s teams and spent a lot of time discussing what shape the set should take. He’s since moved on to do game design elsewhere, and the set has changed a lot since then, but the seeds of his original vision definitely shine through.

Taymoor Rehman – While Taymoor joined as an intern making cards, his love for D&D and extensive knowledge about it were always obvious. Not only is he DMing more games of Wizards folks than you can shake a stick at, but he’s also since moved over to be a game designer on D&D! On Adventures in the Forgotten Realms, he kept us on track for making really resonant cards, with top-down designs and elements of D&D we could mesh with the set’s mechanical needs.

Adam Prosak – Adam has branched out from play design to lead booster sets and has mentored me since I joined Wizards. I worked on his Modern Horizons team and he on my Commander Legends team, and it’s always a treat. This time was no exception, and Adam really helped me find my footing, syncing up flavorful executions while making a replayable set.

Ben Petrisor – Ben carved some time out of his D&D design work to serve as liaison to Adventures in the Forgotten Realms design. Not only did he provide a lot of guidance and feedback about card designs meshing with their concepts, but he also gave us many insights into what D&D finds best-known and most popular with their audience to guide our inclusions.

Kazu Negri – While he’s since moved on to other things, Kazu served as our rep from the Play Design team early in set design and helped keep our explorations of D&D flavor on paths that would work for competitive environments.

Ken Nagle – I’ve worked on a ton of teams with Ken, including Commander Legends, and he always brings ideas from angles nobody else considers and has a keen sense of pain points beyond mere strategic interactions. Here, he used those skills to help us find new mechanical spaces in Magic and executions that dodged physical barriers, like limited table space.

Max McCall – Partway through, Max took over as product architect on Adventures in the Forgotten Realms, shepherding the set through all the numerous stages of becoming a reality. But before that, he lent his great powers of picking out the coolest parts of things to the Set Design team!

Dave Humphreys – Dave is one of Wizards’s most accomplished set design leads, and after getting to learn some of the craft working on his War of the Spark Set Design team, I’ve been glad to have him on both Commander Legends and the early part of this set. He’s especially adept at figuring out how to execute on mechanics and themes to deliver cool, appealing cards and how to work within the pressures of competitive environments.

Ben Hayes – After working with Ben on the digital side, for which he’s director of game design, I was super excited to get his insights on Adventures in the Forgotten Realms. He had a keen eye for the things that I think people will love about this set, and he kept finding ways to capture more of that, beyond game mechanics. It’s thanks to Ben that we have flavor text on basic lands and flavorfully named abilities on creatures and modal cards.

Bryan Hawley – Bryan’s now a game design manager, but that doesn’t stop him from hopping onto lots of teams. It’s been a long time since I was on his Commander (2017 Edition) development team, but I’m still blown away by his ability to pull cool, clean cards out of a huge pile of constraints. That was especially important as we strove to hang onto the resonant flavors of cards through the pressures of competitive play.

Mark Gottlieb – Mark used to be my manager, but we’ve also worked together on numerous sets. He even led vision design and the first part of set design for my next upcoming lead codenamed “Ice Skating.” Mark’s a master of making cards drip with flavor, and he used that talent to kick off our explorations, showcasing things from D&D, but emblematic situations from its wider presence in the zeitgeist.

Aaron Forsythe – Okay, Aaron wasn’t technically on the Set Design team, but he carved out a truly impressive amount of time between his role as vice president of game design and leading Modern Horizons 2 to be involved from start to finish. Aaron pitched Universes Beyond for Magic and always kept his eye on pushing Magic‘s boundaries to deliver on another property in a way that really captured what people loved about it and made it feel right.

Ethan Fleischer – The very first thing I did at Wizards was join Ethan’s Exploratory Design team for Dominaria, and it didn’t take long for me to discover his love for the classics, be they mythology, Magic novels, or older editions of D&D. We had a lot of data on what people play with the most now, but Ethan played a key role in identifying the elements of D&D with through lines across many generations of players.

Zac Elsik – Zac has since left Wizards, but at the time he was a play designer looking to dip his toes into more parts of the set-making process and asked to join this team to get a feel for set design. While doing that, he helped get our draft environment into shape.

Andrew Brown – Andrew leads the Play Design team, and he hops onto the last bit of set design for every main set to help guide it into the play design period. We’ve been friends since before either of us joined Wizards, and we spent endless hours redesigning cards and discussing the big-picture elements of what to prioritize while testing the set. During that time, we ended up concluding ward should be an evergreen keyword and pitching it to the rest of the design group. (Ward premiered in Strixhaven: School of Mages.)

Corey Bowen – Corey spends a lot of time leading design for Commander deck products, including Ikoria, Zendikar Rising, Kaldheim, and Strixhaven, but I steal him for my teams any time I get the chance. Corey brings a firehose of great design ideas and an eye for the cute and funny that’s an essential element of many a D&D campaign.

Now that you’ve met the Set Design team, lets dive into the mechanics of the set. First up is venturing and dungeons.

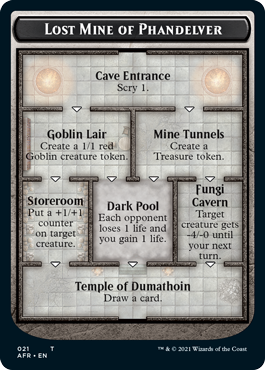

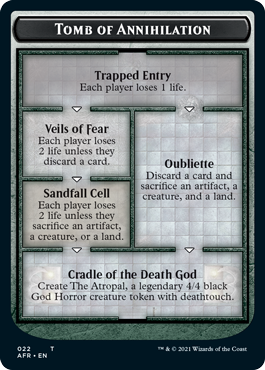

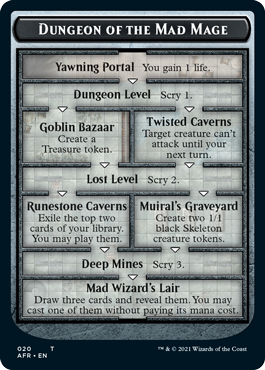

It was a running joke from very early on that Magic had dragons, but it didn’t have dungeons. If we were going to capture the essence of D&D, it seemed important that we find a way to bring dungeons to the set. But what exactly did that mean? What could you put on a card to make it feel like a dungeon? Obviously, we could show you creatures that show up in a dungeon or spells that represent things you do in a dungeon, but none of that felt complete enough. The design team was interested in a mechanic that represented the larger context of exploring a dungeon.

The team did some brainstorming about what exact quality they were trying to capture with a dungeon mechanic. What made something feel like a dungeon? After much discussion, they decided that it needed some sequentiality—that is, you needed to do various things in some order. Venturing into a dungeon was an adventure. The mechanic had to capture the sense that things happened to you as you progressed through it. How could Magic capture that sense of progression? They started by looking at what the game had done in the past.

Sagas

Sagas represent a story. Different things happen over a series of turns. It’s sequential, and it’s flavorful. This is the kind of thing we could adapt into a dungeon. The one thing missing, however, was choice.

Part of venturing into a dungeon is that you, the player, have some agency. You get to make decisions that affect what happens. Sagas had been an earlier version of the planeswalker cards when we first designed them, but we ended up going a different route because it made the planeswalker feel like they were on autopilot. The worry was that dungeons might feel the same way.

Transforming Double-Faced Cards (TDFC)

TDFCs also do a good job of showing progression. You get to see the first side of the card, and then it turns into the second side. You get two pieces of art. It gets to tell a story. The problem is that two parts offer only a very simple story, and dungeons need a little more depth than that. The mechanic is also permanent-centric, meaning it’s more about the people, places, and things than an event.

Adventures

As I said before, exploring dungeons should be an adventure, so why not make something like Throne of Eldraine‘s Adventures? They have two parts and a sense of progression, but only one piece of art. They could capture a moment in a dungeon (Search the Room/Hellhound) but didn’t have the feel of the larger dungeon experience.

Level Up

This shows progression of an object, although it has three stages rather than two (and like an Adventure, only gets one piece of art). Level up could possibly play a role in the set, but is more about adventurers than the dungeon itself.

Contraptions

Contraptions begin the game in a second deck and get onto the battlefield through cards in the main deck. This artifact subtype builds something that creates an ongoing sequence. The sequence loops, but those were the needs of Contraptions; the mechanic doesn’t have to. It also adds an element of surprise because the Contraption deck is randomized. The Set Design team did explore using a second deck early in set design but found that it added too much baggage to gameplay for a set legal in Standard.

They then started exploring some things that we’ve tried in design but never saw print:

Day/Night

This was one of our stabs at making Werewolves (and ultimately transformation) work in original Innistrad design. Cards would bring out an external token that tracked day and night status. As any player cast spells, you would advance the marker on the track, and at some point, it made you flip the card to the other day/night state. You had the ability to speed up or slow down the progression, so there was some agency, but you never really got to make any choices. This was the first time we played around with an outside game component. (The first printed one would be The Monarch from Conspiracy: Take the Crown.)

Skirmish

This was a mechanic created for War of the Spark. Cards would bring out an outside token card that created a little subgame, sort of a tug-of-war where players advanced in their direction for accomplishing certain tasks, including dealing combat damage to their opponent with their creatures. It layered a sequential minigame over the normal game. The flavor wasn’t quite right, but the concept of outside token layering actions on top of gameplay seemed interesting.

In the end, they borrowed elements from many of the above items, but crafted something new. This external token would give you a path with options to choose from, and the path would generate effects that would affect the game. This gave you some agency while also creating a minigame that interacted with the rest of the game.

Set Design would spend a lot of time figuring out what effects to use. Because all five colors could venture (the term they used for starting or advancing in a dungeon), there were many discussions about what kind of effects they could use. In the end, it was decided there were enough hoops to jump through for players that they were okay using simple effects that might not normally be available to all five colors. (Also, they wouldn’t have had enough effects if limited to things all five colors could do.)

The structure to the dungeons were defined by two main things: one, what fit on the card; and two, a desire to give players options. They ended up choosing a single room to start, a forking path, and one or two shared rooms to end. The nature of how the dungeons worked allowed them to make the effects stronger as you progressed through the dungeons. This also added a lot of flavor because, in D&D, dungeons tend to produce bigger rewards (and bigger risks) the further you venture into them.

Next, we examine how rolling a d20 made its way to black border.

Rolling dice isn’t new to Magic. Back in 1998, we made the set Unglued, and it was a major component.

We got mixed feedback on them, so I pulled die rolling from Unhinged, the second Un- set. I would later spend more time with the data and learned that the audience did like die rolling, but only on certain types of cards. They liked having some expectation of what they were getting and that the die roll was a variable in terms of how much the player got, but they disliked when the die roll determined what was going to happen. A deck could be built around the former but not the latter. I would later include die rolling in Unstable, the third Un- set.

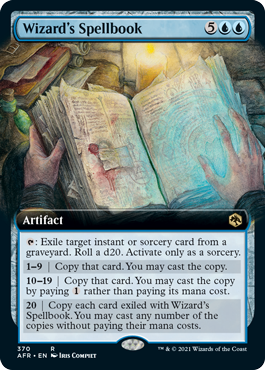

Also in Unstable (it ended up premiering in a Hascon box set but was originally made for Unstable) was this card:

We’d come up with a cool way to reference D&D using a naming convention from a cycle of Swords we did. The original design rolled three six-sided die (you roll three six-sided die to determine abilities), but the D&D team asked if we could change it to a twenty-sided die, as d20s are the most iconic dice from D&D. We did, and Magic got its first card that rolled a twenty-sided die.

Fast forward to Adventures in the Forgotten Realms design. As they looked for things that felt very D&D, rolling a d20 squarely fit their needs. Clearly the Un- sets had shown there was plenty of design space with die rolling, but there was a big question about whether it was something non-Un- cards were supposed to do.

I believe the earliest designs involved rolling a twenty-sided die with two possible results, 1–10 and 11–20, the idea being that this was just a cute way of doing a coin flipping card, and those were already in black border. (The team later made them 1–9 and 10–20 to make them not technically coin flips.) The team also stumbled upon the same information I’d learned from the market research about how best to use die rolling.

This led them to making die rolls where there were three outcomes, usually 1–9, 10–19, and 20. Most of the spells used rolling a die to determine how big the effect was going to be with each output connected. The 20 allowed for an extra exciting thing that would happen infrequently.

The team was also very careful about using die rolling on cards that were relevant in Limited and casual Constructed but wouldn’t be the kind of thing a tournament game would hinge on. The other big innovation was figuring out that they could use the dice chart technology from D&D to represent the outcome in the text box.

The bigger challenge wasn’t the design but getting a majority of R&D on board with rolling a d20 in a premier set. Because it was so closely associated with Un- sets and is obviously tied to an object that embodies randomness, many R&D members felt it was out of bounds.

There was a lot of back-and-forth and tweaking of the die-rolling cards before consensus was reached. I think a big part of it succeeding was the fact that it was for the Dungeons & Dragons set.

Now, we’ll examine how the Class enchantments made it into the set.

Another iconic element of D&D is leveling. As your character gets better, you go up levels that increase how powerful your character is and what abilities they have access to. Clearly, the D&D set should have leveling.

The first place they looked was the level up mechanic from Rise of the Eldrazi (which I talked about above). It obviously was designed to capture exactly this flavor. There was just one small problem. The person who levels up in D&D is you, the player. Level up made your creatures better, not you. Was there a way to let you level up?

The design team then took the basic structure of a level up creature and applied it to the player as a general enchantment. They made two basic changes. One, each leveling up had a single mana payment (level up had you pay for level counters, and then told you at what threshold you upgraded). And two, the effects were enchantment-style effects that granted abilities. It turned out that we could use a variant on the Saga frame to represent this new subtype. All that remained was to take the popular classes from D&D and turn them into cards.

Another unique aspect to Adventures in the Forgotten Realms was a technique to add flavor. Many abilities have what we call flavor words to show how the spell would be represented in D&D. The words are italicized, much like an ability word, and help add a touch of D&D flavoring. The design team found a clever way to make use of these flavor words.

By adding flavor words to modal effects, they could create cards that capture a sense of being on a D&D campaign. The cards were then named (mostly starting with “You”) to play into this feel of being in the middle of a D&D session.

That’s the design story of Dungeon & Dragons: Adventures in the Forgotten Realms. I hope you are all as excited to play with it as we were to make it. As always, I’m eager to hear your feedback either on today’s article or on the set itself. You can email me or contact me through any of my social media accounts (Twitter, Tumblr, Instagram, and TikTok).

Join me next week when I share some card-by-card design stories from the set.

Until then, may you have glorious adventures playing Adventures in the Forgotten Realms.

#849: Future Sight with Mike Turian

#849: Future Sight with Mike Turian

36:16

I sit down with R&D member Mike Turian to talk about the making of Future Sight.

#850: Faeries

#850: Faeries

30:16

In this podcast, I talk about the history of the Faerie creature type in Magic.

[ad_2]