[ad_1]

March 24, 2023

·

0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

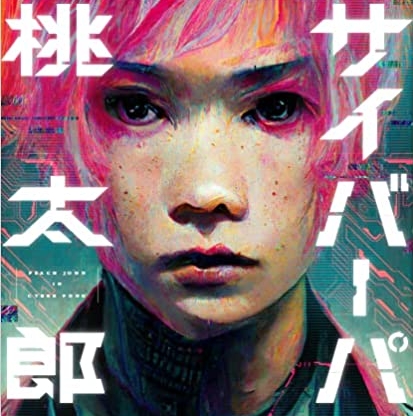

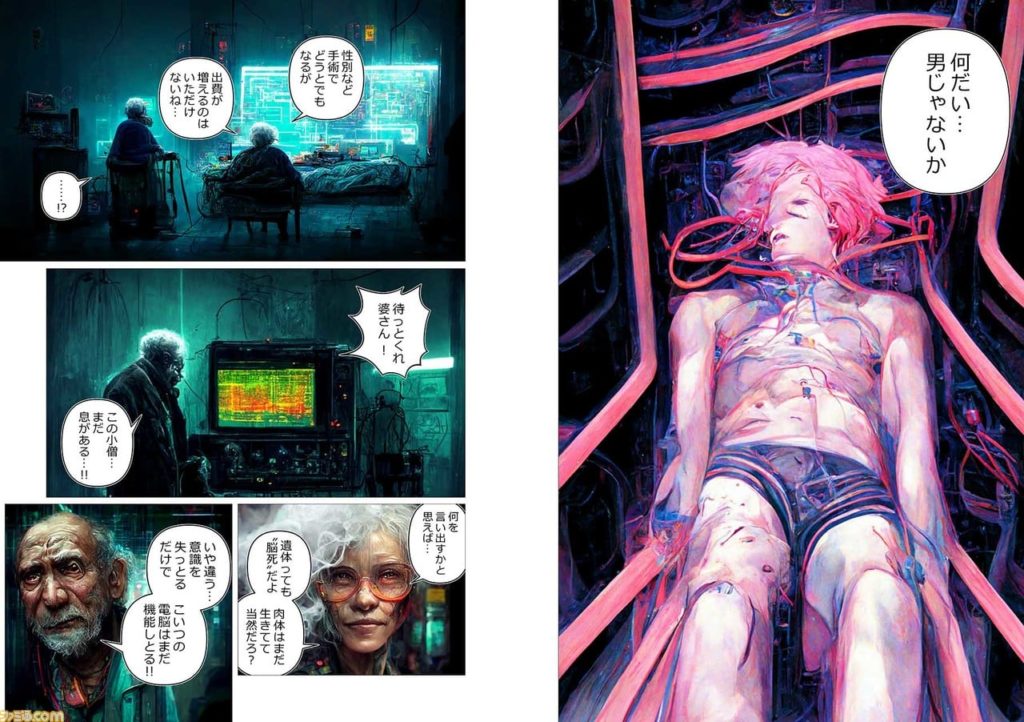

Ironically, there is nothing new about the plot of Rootport’s Cyberpunk Peach John. Despite a media frenzy about the way it was created, a year’s worth of colour artwork assembled in just a couple of months by a pseudonymous creator using artificial intelligence software, the story itself is as old as the hills. Neo-Okayama is a city cast in the mould of Blade Runner or Neuromancer, all very 1980s. The pink-haired Peach John is an amnesiac hero, entrusted with valuable data, re-enacting the fables of Momotaro in a futuristic urban setting – assisting an old couple, a hacker and a fence for stolen data, laundering money through a neon-lit strip club. His sometime assistant is the unfortunately named Wanko, a pretty girl with dog’s ears.

This is the water we are all swimming in now. Bearing in mind the flood of AI-generated stories sent to Clarke’s World, leading the science fiction magazine to temporarily suspend submissions, the first question I’m tempted to ask is why Rootport didn’t leave the story to an AI as well, but no matter. His achievement is spectacular enough, creating a 120-page manga, in full colour, even though he admits himself to being hopeless as an artist. Instead, Rootport put in that all-important labour of “human fallback”, sifting through thousands of AI-generated images in search of the ones that he could link together to tell his story.

According to Rootport, Japanese AI users call the initial generation of content “turning the gacha”, in reference to the gachapon dispenser machines that deliver random toys. “You cannot necessarily get the image you want in the first attempt,” he writes. “Change words and word order to adjust the spell to make the image closer to what you visualise.” In the case of the prompt “cyberpunk momo-taro midnight Japan”, the AI engine initially seized upon the term Momo, which does mean peach, but is also a girl’s name, flooding his screen with pictures of girls. Instead, he had to specify: “pink hair, Asian boy, cyberpunk, stadium jacket, manga” before he started to get the image that he wanted.

Rootport specified “pink hair” because he soon realised that the AI would not always be consistent. In other words, many of the images generated would be “off-model” from whichever one he initially selected. In order to misdirect the reader from noticing those moments where a character’s appearance drifted away from what it had initially been, he chose specific, obvious traits, such as pink-hair or dog-ears, as a form of short-hand to distract the reader. And the reader certainly needs distracting, as Peach John’s hair colour is the only part of him that remains consistent from frame to frame.

“For example,” Rootport writes, “if it’s a ‘young Asian woman with wolf ears’, the readers will see her as Wanko, even if she’s got the wrong face.”

Rootport was not satisfied with every element of his project. In particular, he was annoyed at his AI collaborator Midjourney’s inability to express human hands, which he regarded as a “second face” in terms of imparting data and drama to a reader. He also soon realised that he was asking too much of Midjourney to generate backgrounds and characters in the same image, choosing instead to create those elements separately, and then composite them together manually to avoid wasted time.

Taking a leaf from the playbook of Osamu Tezuka, he also generated an image bank. If Midjourney got something right, Rootport would make it generated hundreds of similar images, particularly of human expressions, which he could then drop in to later images. Which is all very well, but one wonders how swiftly fatigue will set in among readers. Cyberpunk Peach John, retailing at 1300 yen (£8.00) is a landmark in the history of manga, but it’s a “first” like the first colour movie or the first pop-up book, rushed into stores for its early-bird nature and its value as a snapshot of what new technology can do. Except in the days of machine-multiplication, “new” isn’t what it used to be.

Even Rootport’s afterword account of working with Midjourney is now a historical document in the rapid pace of AI development. His experience, his achievements and his complaints all relate to a version of Midjourney that was superseded last autumn. In the time it has taken his book to make it to the bookstores, the AI has evolved another generation.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Anime: A History. Cyber Punk Peach John is published in Japanese by Shinchosha. Additional reporting by Motoko Tamamuro.

[ad_2]