[ad_1]

The key to a good mystery, in my opinion, is narrative constraint. When the rules of a mystery – what the investigator can and cannot do, who and what was where and when – are laid out clearly for the audience, working within those limitations to puzzle out the case (a la any book by Agatha Christie, the who-dun-it queen) becomes irresistible.

Conway: Disappearance At Dahlia View knows exactly what its story, and its protagonist specifically, can and cannot do. Robert Conway can use his decades of experience as a private investigator to look for missing child Charlotte May Morgan, but what he cannot do is leave Dahlia View or get caught by the police. Confined to a wheelchair, Conway surveys his neighbours from the window of his second-floor flat, occasionally venturing down into the quiet courtyard below to infiltrate his neighbour’s homes. Though due to the declines of age or sheer arrogance, he does neither half so subtly as he’d like to think.

Within these constraints, Conway presents a classic locked room mystery, only the “room” is the neighbourhood of Dahlia View and, unbeknownst to Conway but made known to the audience, this has all happened before.

Conway’s neighbours know they’re being investigated – both by a nosy pensioner and by police officer Catherine Conway, who also happens to be Robert’s daughter. They also know that the person who abducted Charlotte May must be among them, and yet no one seems particularly concerned about getting caught… for kidnapping, at least.

Due to Conway’s limited mobility, he isn’t able to take part in the daily search parties, but instead commits himself to a series of investigations split into three parts: Observation, Search, and Evidence. The first stage, Observation, is perhaps the most titillating, as it involves some good old fashioned snooping on his neighbours from the bay window of his apartment. This is done through an engaging photography mechanic in which a gold viewfinder identifies activities of note in the street and adjacent flats. Snapping photos of the couple across the street arguing or an aging widow sneaking around her own home is enjoyable, contributing naturally to the suspicion that some small part of Conway is grateful for Charlotte May’s disappearance, if only to give him something to do.

Next is Search, in which Conway employs a blend of stealth and charm to worm his way into his neighbours’ homes, with or without their permission. Once again, the player is rewarded with an opportunity to poke about in other people’s private lives and solve a number of fairly straightforward but satisfying puzzles. These range from cracking cyphers to setting up a beer cask and draining a basement, in addition to perhaps my favourite lockpicking minigame ever (a combination of maze solving and hand-based Twister).

While things get a bit more complicated as the game goes on, these puzzles generally make for smooth sailing – presenting just enough of a challenge to feel like you accomplished something without getting too frustrating. It quickly becomes clear that anything you can pick up, you should pick up, which keeps the game marching forward without much need to circle back for necessary items.

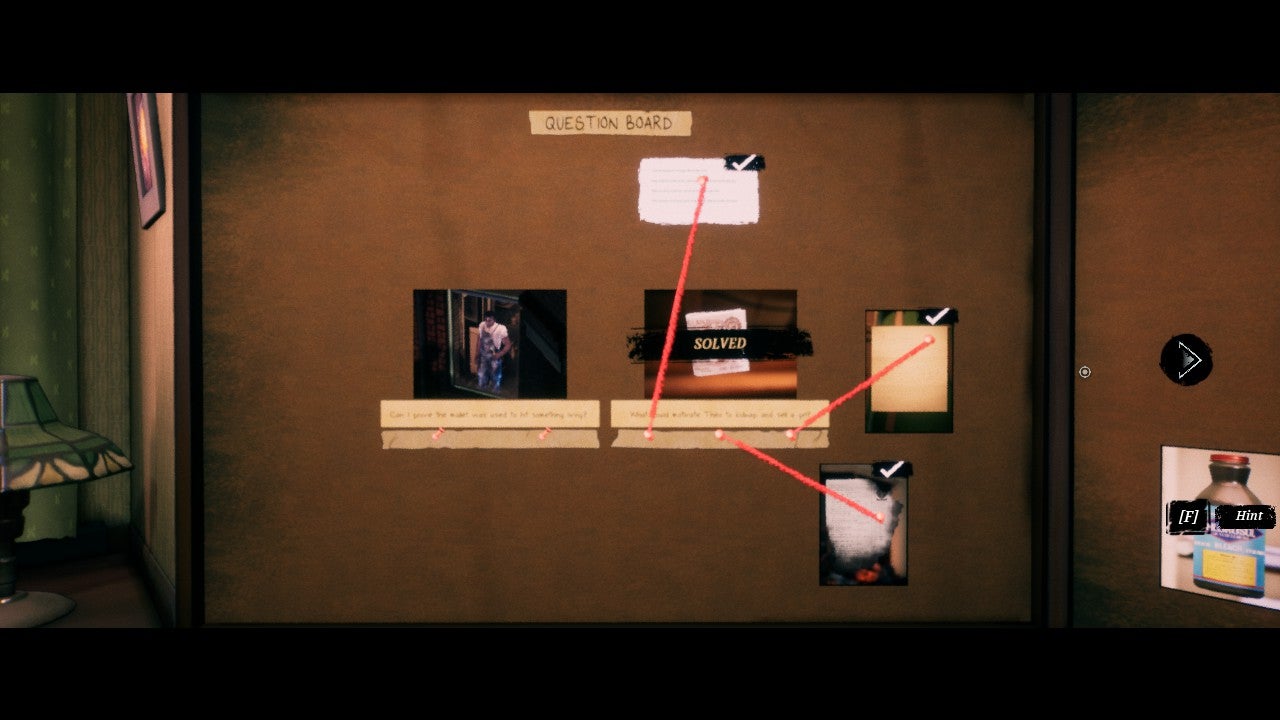

The last, but most important, stage of the investigation is Evidence. At this point, Conway presents each of his findings on a question board, and it’s up to you to figure out how they all connect to reveal something your neighbour doesn’t want you to know.

It all comes together successfully. While the mystery of what happened to Charlotte May isn’t the biggest mind twister ever, in this genre I consider that a compliment. Rather than seeking to toss the audience on its head with a twist no one could ever see coming (I’m still looking at you Heavy Rain), Conway’s story makes sense. So if you’re paying attention it’s possible to figure out where it’s going before it gets there. Gameplay aside, the story stands on its own, and could work easily as a novel or television show without relying on the illusion of choice to draw you in.

That said, Conway makes the most of the medium while sticking with a linear storyline. The voice acting is first class all round. Every character has a distinctive and memorable way of speaking, and maintains a soothing, yet serious tone throughout. Similarly, the art style has a half-drawn, half-realistic quality to it that has an almost dream-like quality. Each scene is presented from a fixed view point, allowing for intentional, cinematic framing of shots. While this occasionally created some navigation issues – especially later in the game when the developers clearly wanted you to take Conway down a particular but not necessarily intuitive path without resorting to a fully automated cutscene – the overall effect is wonderful.

All of that is interspersed with numerous lingering shots of London’s far off skyline – out of reach, but just present enough to suggest there’s a wide world out there of which we are seeing just a small part. Within that little snow globe, there is Conway, constantly reminding anyone who will listen of his past life as a private detective. The game is well aware of the fine line between that part of his past and the possibility of Conway as little more than a bored retiree with nothing better to do than eavesdrop on his neighbours. It’s never quite clear, right up until the end, if he’s digging up damning admissions of guilt or petty instances of private scandal that he could easily be blowing out of proportion in his fervor to relive the glory days.

Conway has a sharp mind, but his neighbours are just as quick witted, and everyone has a secret. Even so, Conway manages to skate above the tired surface of more cynical takes on human nature common in “gritty” crime dramas nowadays. Dahlia View’s residents are selfish and short sighted, perhaps, but they all mean well, or at the very least aren’t actively looking to hurt anyone as long as they get their way.

It’s all collateral damage in pursuit of their own narrow goals, and Conway’s motives are no different. He wants to find Charlotte May for her own sake, yes, but, more than anything, Conway is racing against time, his body, and the police (who he refuses to collaborate with on numerous occasions, despite having ample opportunity to do so) out of a desperate, near obsessive desire to prove to himself that he is still the detective that can crack the case.

As Catherine suggests, you can try to pretend your actions don’t affect other people, but there is always a cost, and I would whole heartedly recommend than any murder mystery buff find out exactly what those costs are for Dahlia View.

[ad_2]