[ad_1]

By Jonathan Clements.

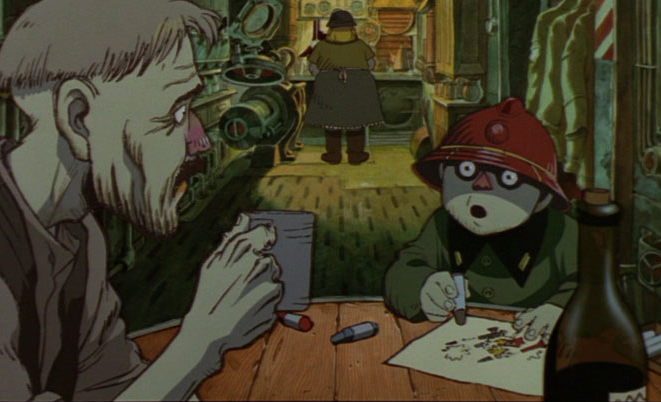

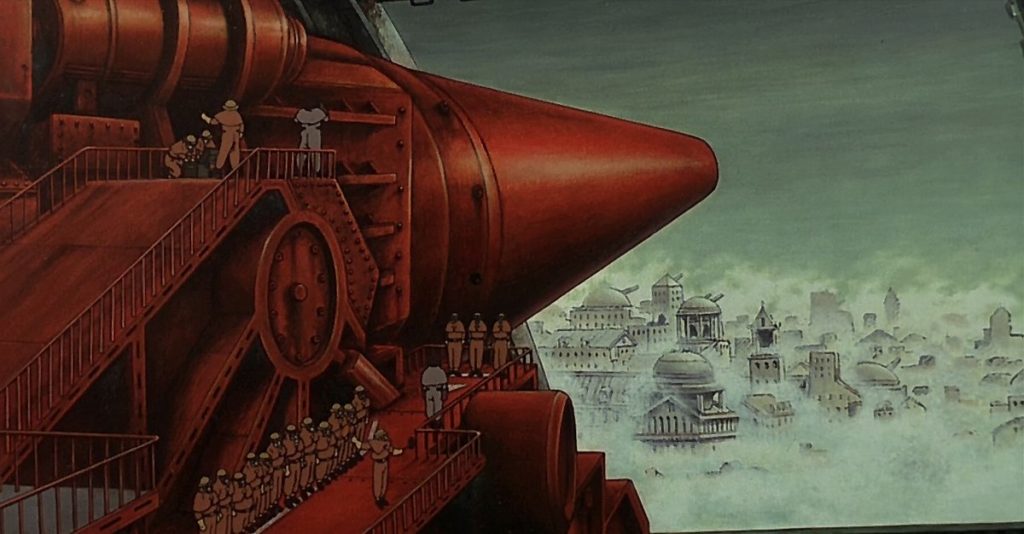

From the opening moments of Katsuhiro Otomo’s Cannon Fodder, the third and final story in the Memories anthology movie, we find ourselves in a world dominated by military thought. Even the striking mechanism of the Boy’s clock depicts a cannon destroying a castle. Everybody’s job is connected to the war effort; everybody’s education is connected to the war effort; everybody’s entertainment is, too. Katsuhiro Otomo’s short vignette recalls the deadly drift in the early 20th century towards the Wehrstaat, a state in which every scrap of society is dedicated to national defence.

He presents a day in the life of an average family in this terrifying place, their every waking moment dominated by the fanatic mission to fire giant shells at an unseen, and possibly non-existent enemy. But the real story is revealed through multiple asides, questioning the just cause of the war they are fighting, the intentions of the government, the mettle of their heroes and the safety of their working environment. In that regard, it echoes Osamu Tezuka’s early animation short, Tales from a Certain Street Corner (1962), in which the collapse of a nation into fascism is told largely through the kind of posters and adverts pasted on a particular wall.

Cannon Fodder’s world is grimly defined by the technology that it serves. Steam powered hydraulics rule the infrastructure. Gun-derived technology has seeped into Mother’s kitchen-range. The roofs of the houses support multiple gun emplacements, and there are asides that the rest of the society is entirely militarised – train stations are mere numbers, on streets that are themselves mere numbers.

“I asked Hidekazu Ohara to be the character designer and animation director,” says Otomo, “and I told him: ‘Rather than ordinary animation, let’s make this in a more hand-painted, non-typical cel-animation style.’ In other words, I wanted Cannon Fodder to look more like a painting.” And indeed, there is a strange, baroque beauty to the middle-European-influenced streets, through which our pallid, drawn figures tramp to work. And there is a growing sense of wonder as the viewer realises that Otomo is shooting his 22-minute closing vignette as one, single take.

In some senses, this is easier in animation than in live-action. Sharp-eyed viewers will be able to pick out certain moments where one cel frame has been attached to another to make it look as if a door is opening or the camera is tracking around a particular character, in order to wipe between actual shots. It’s the joins you can’t see that are the scariest, as the animation-savvy viewer wonders if they were shot not on a standard-sized cel, but on some giant, elongated monstrosity, being fed in front of the camera millimetre by millimetre. In other cases, it is merely something that appears like that, with backgrounds showing two different sides of the same wall, scanned and pasted into 3D software so that the characters can walk around it with changing angles. That, however, only created new problems, since looking at a wall head-on is not the same as looking at it from an angle. “So, we experimented with pictures that had a slight perspective to them, in a style of a trompe l’oeil to see how we should paint to achieve the most effective way.”

For some shots, Otomo used the Imagica Composite Image Systems Electronic Optical Suite, which combined the functions of telecine transfer and video compositing. Whereas his colleague Tensai Okamura was struggling over at Madhouse to integrate six different planes of movement using simple cels in Stink Bomb, Otomo was able to use CIS technology to created long tracking shots, walk-and-talks through bustling activity, and backgrounds hissing with steam and motion.

This, too, brought unexpected challenges, since CIS was already an aging technology designed for video, and not intended for being blown up into images the size of a cinema screen. “When printing the image on film of a vista size,” remembers Otomo, “the image becomes grainy. It might have been fine if it were High Vision video, but CIS was a digital format from a generation earlier. Still, the advantage was that the colours do not change when you composite them, which they do with an optical printer.”

Even so, Otomo sent himself repeatedly back to the drawing board, particularly after he discovered that his original idea for a constantly moving camera would leave the audience feeling ill. He experimentally used a video camera to shoot his storyboards at the speed of the intended shots. “It turned out to be extremely fast. It gave you motion-sickness. The camera kept moving all the time, and it looked like a video shot by an amateur. You need to stop sometimes. You need to slow down when have to. You need a variation of pace, otherwise it is difficult to watch. Therefore, the actual film has different timings from the storyboard.”

Memories, released in the year of Windows 95, was made on a technological cusp of the expansion of computing power and the rise of digital processes. Some of the techniques included in the final print were literally impossible to achieve three years earlier when the film commenced production, throwing Otomo and his staff into a constant game of catch-up with new developments in processing and materials. In a sense, his celebrity in the anime world forced him into the role of an early adopter, tinkering with new technologies when they were still expensive and untried. Similar issues would confront him on his later work, Steamboy, which also faced a series of technological pivots mid-production, as computers were suddenly able to do things they couldn’t do before. But Otomo has always stressed that while critics often talk about Cannon Fodder as a digital work, many of its stand-out moments and images are born from old-school techniques. One of the film’s most intricate shots, which whisks the viewer away from the firing gun, across the town and through the window of a faraway factory, is a little-known achievement on the resumé of the multi-plane camera operators at Studio Ghibli, who were tasked with creating an almost impossible juggling act of planes and motion.

As for the colours, they were born of unconventional materials rarely used in Japanese animation. “We dropped the brightness and upped the overall saturation. When it comes to the background, they used materials that had not been used much in conventional animation, such as Liquitex and acrylic gouache rather than poster colours…. Because the background looks like a picture book, for the cels I wanted to add touches with coloured pencils on smoky cels. I wanted to have that coarse feel, or the pictures drawn on a paper kind of feel. However, smoky cels have a lower transparency, so when put that on a background, it kills the colours of the background.”

For his work on Cannon Fodder, Otomo pushed both the multi-plane camera and the optical printer to the very limits of their functions. “If I wanted to try something more,” he admitted, “the only way will be to use a computer.” On his next anime feature, Steamboy, that is exactly what he did.

Cannon Fodder is loaded with intricate, tiny details that reward repeat viewings. It was only the third time I saw it that I noticed some of the support struts in the 17th Cannon Station had been stripped of their plating, as if the inhabitants of the city were ransacking their own infrastructure to support the war effort. Propaganda messages festoon the city, written in English but in a semi-Cyrillic font that often requires a freeze-frame to appreciate: “No Conquest Without Labour” being one of the most on-point messages. Otomo’s one-take deception only really comes to an end in the closing seconds, when the cartoon-like images of the Boy’s militarised imagination cross-fade into the portrait of the heroic gunner that hangs in the family’s hallway. The Boy winds the clock at precisely nine (“Heaven at Nine O’Clock” being one of the blink-and-you’ll-miss-them propaganda messages), and then he falls into a dead sleep, while the sounds from the street outside suggest that his society is not as unified of purpose as it claims.

The noise of a searchlight bathes his bedroom with a blue glare, and then segues into “In Yer Memories”, the house-music track which samples and revisits multiple moments from the film we have just seen, including snatches of big-band trumpets, and fragments of operatic chorus, all weaving around a thumping beat. It is, in every sense of the word, a calculated, upbeat reverie on the movie as it comes to an end, an antidote to the grim philosophising of Cannon Fodder and the Twilight Zone twists of the films that preceded it. Otomo had originally planned to solicit an ending theme from one of the composers who had worked on the separate movies, but with time running out, he instead turned to the Denki Groove DJ, Takkyu Ishino. “You get a still image from the title ‘Memories’,” said Otomo, “but I asked him: ‘Please turn the cinema into a dance floor.’”

Jonathan Clements is the author of Japan at War in the Pacific. Katushiro Otomo’s Memories is available for pre-order from Anime Limited.

[ad_2]