[ad_1]

I love worldbuilding. As a young Dungeon Master, it didn’t matter how long it took to sketch out the buildings of my pirate island or name every member of its ruling syndicate, even if my players ultimately would decide to sail right past it. As a father of a newborn, however, I’m lucky to find three hours a month to squeeze in a game on Zoom, let alone flesh out a fictional continent. Fortunately, limited time need not keep you from the joy of homebrewing a campaign world. If you’re willing to accept it, much of that work was already done when your players created their characters.

Building your world piece by piece

No campaign world needs every detail in place at the start. Take the most commercially successful fantasy setting, the Marvel Universe, for example. It features hundreds of characters in a vast cosmos, and an alternate New York every bit as intricate as Waterdeep. But it’s not like Stan Lee sat down and came up with all of it before he plotted his first story. It came together one element at a time.

J. Jonah Jameson was created to bedevil Spider-Man. But with his addition, there now existed a newspaper editor who could appear whenever one was needed. SHIELD was conceived to give Nick Fury gadgets, but Lee soon realized they could appear in Iron Man and Captain America’s adventures just as easily.

Follow a similar approach when fleshing out your homebrew setting. Create key locations and a supporting cast for each of your players’ characters. Do that and, before you know it, your world will take shape.

Finding inspiration in character sheets

Your players’ character sheets offer more than enough guidance on people and places you need to populate your world. For example, the characters’ chosen languages are an indication of who they want their character to interact with, or else why pick them? Of course, one Infernal-speaking character in the party doesn’t mean you have to create a town full of pit fiends a mile from the starting Inn. Your world should satisfy your creative vision as well as your players’ needs. How you incorporate the language into your setting is up to you. A wizard’s guild might inscribe spells in Infernal, or a cult might use it to encrypt messages. The important part is that your players have opportunities to use the skills they envisioned for their character.

Bonds, flaws, personality traits, and ideals aren’t just tools for players to get a handle on their characters, either. To the attentive Dungeon Master, they’re an invaluable snapshot of the world that the players envisioned their characters running around in. The DM need only filter the players’ choices through their own imagination for their group’s ideal campaign setting to emerge.

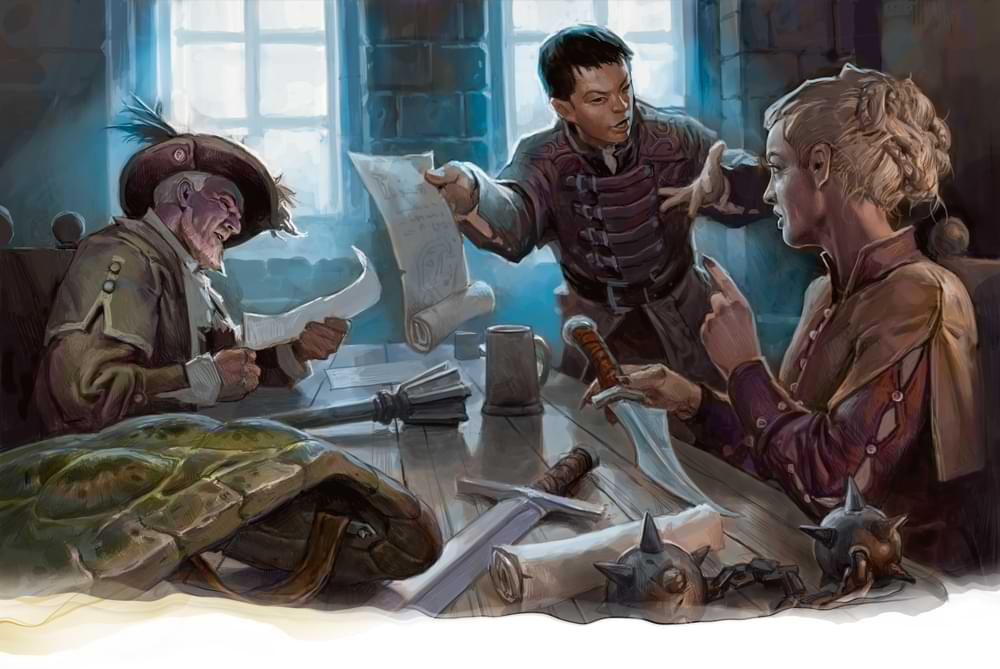

I discovered this method of worldbuilding by accident after agreeing to DM five new players over Zoom. I was unable to see their characters before the session, but I had an adventure ready. They would be the newly captured security detail of a human baroness, currently imprisoned in a mountaintop fortress. The evil wizard who lived there had been paid to charm the baroness out of her claim to her territory.

The adventure ended up being a lot of fun. The party escaped the wizard’s fortress on the backs of giant sparrows after killing him and his many apprentices. We decided to play again the following month, though I had no idea what lay ahead of them or when I’d have time to figure it out. Thankfully, ideas began to present themselves as I looked over my players’ characters. None of them were human, so my baroness’ realm would include areas where nonhuman races were commonplace. Perhaps, I decided, she was touring the wild north of her territory with local protection when she was captured.

Creating my first faction

Details sparked further inspiration. The paladin was a goliath. They lived in the mountains. My wizard’s castle was also in the mountains, so I decided the nearest town would sit at the base of a mountain range containing the goliath village of Sky Haven.

The goliath paladin’s creator chose the Acolyte background, with this bond: “I will someday get revenge on the corrupt temple hierarchy who branded me a heretic.” I checked his alignment: lawful good. His temple must have turned from those values at some point. That led to my world’s first faction, the Sunshields. They would be an order of corrupt paladins shaking down the faithful for “protection.” The sun god’s symbol on their shields now stood for banditry and corruption. To represent them, I created the cheeky, bigoted Sir Cassius Fairfax, who trained with the young goliath and never accepted him. After reviewing just one character sheet, the world was off to a great start.

Finding the villain’s motives

I decided that the evil wizard the characters killed made his living making potions and his death shut down production on the month’s orders. His business partner, the half-elf Cullen Moonglow, now had to figure out how to protect his town from 100 angry empty-handed potion customers, including Cassius and a nasty crew of Sunshields.

Considering character subclasses

A player’s choice of subclass can be just as instructive. A Way of the Four Elements monk requires other such monks to train him. Your setting might contain dozens in a well-funded hilltop monastery or just one wandering master in a beat-up wagon, seeking out potential students he sees in visions.

The high elf in my players’ party was a Draconic Bloodline sorcerer with fire spells. Suddenly, I had my main villain faction. The high elf’s draconic ancestor, the red dragon Auraxian, once ruled the barony. He was slain 200 years ago by the baroness’ grandfather. An alliance of the dragon’s other descendants, our high elf sorceress’ cousins and half-brothers, wants to return the barony to draconic rule. So, that’s who paid the evil wizard to capture the baroness. And the characters’ homes were directly in their path.

From just five character sheets and an hour of brainstorming, I had a brief history of my territory, basic geography, major factions, government, and population.

Bringing your players’ world to life

Watching your players bring your homemade world to life is one of the joys of being a Dungeon Master. Don’t let limited time stop you from experiencing it. Having your players use tools like the “This Is Your Life” chapter of Xanathar’s Guide to Everything will help you create an even richer and more resonant setting for your players, one that is more likely to engage them and less likely to be sailed right past like the poor pirate island I spent so many fruitless hours on years ago.

Comedian and writer John Roy (@johnroycomic) has appeared on Conan and The Tonight Show and written for Vulture and Dragon Plus. He is the co-host of the comedy/war gaming podcast Legends of the Painty Men. His albums can be found on Apple Music and Spotify. He splits his time between Los Angeles and the Free City of Greyhawk.

[ad_2]