[ad_1]

October 24, 2021

·

0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

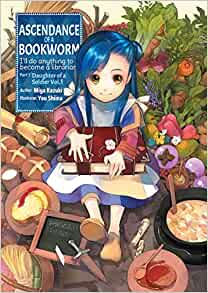

And then a pile of books fell on top of her, and she was dead. That can’t possibly be the beginning of a tale, can it? But Miya Kazuki’s fantasy series Ascendance of a Bookworm wastes little time describing the humdrum, Earthbound life of its heroine, Urano, before it kills her off in an earthquake, and whisks her away to the fantasy land of Ehrenfest. There, she wakes as a younger, feebler person – Myne, a daughter of a soldier in a grungy medieval kingdom.

And so, it’s yet another tale of a Japanese twenty-something, spirited away to a mysterious otherworld, except Urano isn’t so keen on this one. For starters, she is revolted by how dirty everybody is, and she is soon missing the mod-cons of a Japanese bathroom. But worst of all, worse even than the fact that her Dad is now apparently a green-haired man called Gunther, is the fact that she has found herself in a world without books.

I know that horror. I was once a guest in someone’s home where the sole piece of visible literature, left out on the coffee table to impress visitors, was a Dan Brown novel. So. imagine finding yourself in a world where not even a Dan Brown novel is available, where despite having Swedish-Finnish names, the locals have never heard of a sauna or soap… and did I mention there were no books?

In fact, there are books, but they are only bespoke, hand-scribed curios for the elite, and unlike many a Japanese fantasy-novel protagonist, parachuted into the upper echelons of society, Urano has ended up in the malnourished, sickly body of a child of the medieval underclass.

Dear reader, I am sick of Japanese light-novel characters, whisked away to saccharine, barely described other-worlds based on some teenager’s half-remembered sight of a video game. But Urano is eternally, comedically aghast at the stench of her new home, the dangers of rotting meat in the marketplace, and the adults’ hand-waving attitude towards giving alcohol to children.

Whereas the leading man in How a Realist Hero Rebuilt the Kingdom is basically handed a nation on a platter and goes around fixing things by decree, Urano has to rebuild her new home-world from the ground up, starting by making her own shampoo with a mortar and pestle, and trying to persuade her family members to clear out the lice and spiders and try using soap. All this, however, is a prelude to her grand enterprise, a quest to create books from square one – making her own paper, learning how to saddle-stitch and bind, and even writing them herself.

No wonder this series has a zillion volumes – in a cunning exercise in self-reflexivity, author Kazuki is gently introducing the reader to the huge, multi-century technology tree that would ultimately end with the book they are holding in their hands. She does so by taking Urano through every single stage required to make a book happen, as if someone suddenly said “Let’s go for a drive”, and then first had to invent the rubber tyre, and the car, and asphalt, and the paint to make the white lines on the road.

Urano drags her parallel-world sister Tuuli to the forest to get the materials for papyrus, or the best guess she can make at this world’s version of papyrus. She searches for alternative sources of ink, either made from scratch or as something she can barter from others. All the while, she tries to explain her plans to her family, but every word that does not exist in the alternate world just comes out in unintelligible Japanese.

Some suspension of belief is required in the sense that Urano alone is clued up about the various foodways and technologies of the ancient past. She tuts that Myne’s mother doesn’t think to use the bones of a game-bird to make a hearty broth, which stretches this reader’s credulity a little because a realist other-world would surely have an almost entirely clueless visitor from our time, learning from the locals about techniques now forgotten in the modern age. Certainly, in my travels among the ethnic minorities of South China, I was perpetually amazed at the cunning, hard-won knowledge of various folk-arts – I was, indeed, taught by the locals to make paper from mulberry bark and viscous sap, I have dyed clothes using indigo leaves, and made musical instruments from scratch, starting with an axe and a tree trunk and ending up with a guitar. At literally no point did anyone stop, baffled in the middle of their work and hope that the City Boy would explain something he had read about in a book once. I was, inevitably, a fish out of water, a man from our world turned into a pointless dunce, unable to even light a fire.

Urano’s excuse is that her own mother back in Japan was something of a back-to-nature nut, but the way she tuts and sneers at the people of Ehrenfest strikes a discordant note with me. They can’t possibly be as stupid as she makes them out to be, otherwise they would all be dead. As a case in point, Urano patronisingly explains to everybody how to make a stew, as if that would not be the default meal in any pre-modern society. The people in this fantasy land have all the ingredients they need to make gnocchi or steam things in saké, but it has never occurred to them to do so before Urano’s arrival.

But beyond this wish-fulfilment idea that an entire primitive society is just waiting for a Japanese nerd to show up and invent shampoo (an item, incidentally, that East Asia has had since at least the Dark Ages), Ascendance of a Bookworm is a winning, slow-burning tale of how technology can change a society in tiny increments, and not always for the better. This first volume ends with ominous signs that Urano/Myne has already attracted envy and avarice among some of her fellow medievals, who apparently have never thought of tying their hair up with a stick before.

Ascendance of a Bookworm is published by J-Novel Club.

[ad_2]