[ad_1]

By Andew Osmond.

Anime’s first ever star was an A.I. character, Osamu Tezuka’s Astro Boy. While the series stressed the boy bot’s Kryptonian-level powers – 100,000 horsepower, in Tezuka’s phrase – the anime also made clear his mind, his personality, compassion and principles are entirely artificial. Like most A.I. characters in anime, Astro Boy is embodied in anthropomorphic form. He’s in humanity’s image, only cuter.

Astro Boy debuted in anime in 1963. Three years later, 2001: A Space Odyssey depicted the most iconic A.I. in Western cinema – the camera lens, red dot, and lethally calm tones of HAL 9000. HAL is the archetypal computer that says no (or, with a word-perfect courtesy to resonate in the age of ChatGPT, “I’m sorry, Dave, I’m afraid I can’t do that.”) That image is in tune with our perceptions of A.I. now, something which transcends humanity and will destroy us like a digital Frankenstein’s monster.

Anime, though, is more hopeful.

There haven’t been loads of anime “killer computer” stories, full of Terminator Skynets or their cinema relatives, such as Colossus (in Colossus: The Forbin Project) or the subtly-named Doomsday Machine (in Dr. Strangelove). One of the closest anime examples is the Love Machine in Mamoru Hosoda’s Summer Wars. This virtual villain manifests in cyberspace as a sniggering Mickey Mouse cosplayer or a demon martial artist, wreaking havoc on the “real” world.

Hosoda himself acknowledged Summer Wars was inspired by another Western movie about A.I. apocalypse, the 1983 thriller WarGames. Interestingly, though, that film’s A.I. was characterised as an innocent which begins by thinking “Global Thermonuclear War” was as harmless as noughts and crosses. In Summer Wars, the A.I. isn’t nearly as sweet; Love Machine acts like a school bully. Yet Hosoda himself didn’t see it that way when I interviewed him in 2011.

“I think he’s more like a little child than a violent bully,” Hosoda argued. “He might not have the intention of doing harm to other people or to the world. He was programmed to study and grow by himself. His curiosity and longing for knowledge brought the world into chaos.”

You can argue that Japan’s optimism about A.I., and robots with A.I., has roots in the country’s post-war history. Mamoru Oshii, director of Ghost in the Shell, suggested just that in an interview in Toronto in 2014. “Back when I was a child, Japan had just lost the war, so the whole country was very poor. Then we started getting TVs and refrigerators and some households were able to afford cars… Having these new machines was foreshadowing a brighter future. The Japanese always had an image of happiness by having all these new machines and scientific technology.” Tezuka’s Astro Boy debuted in manga form in 1952, right in the time Oshii describes.

More contentiously, you might point to older traditions. In Japanese religion, there’s a long history of pantheism – the belief that supposedly inanimate objects have a soul. Notably, Masamune Shirow, who wrote the Ghost in the Shell manga, says he believes in a form of pantheism in the strip’s endnotes. Pantheism is more accommodating of artificial life than the Christian tradition. Consider how Frankenstein’s creature is denounced as a “daemon” in Mary Shelley’s novel, or how the evil android in Fritz Lang’s 1927 film Metropolis is a witch to be burned.

That’s in stark contrast to the android girl Tima in the 2001 anime Metropolis. That film merges elements of Lang’s classic with the sensibility of Tezuka to envisage Tima as another AI innocent, plaintively asking, “Who am I?” Tima is a victim of humanity, conceived as a weapon with no allowance for her emerging consciousness. As such, her plight’s like that of America’s The Iron Giant (“I am not a gun!”) and also the Puppet Master in Ghost in the Shell.

The point’s easy to miss in the latter film. On casual viewing, you may think the Puppet Master in Ghost in the Shell is “responsible” for the misdeeds attributed to it. For example, it ruins the life of a luckless garbage-man, giving him fake memories of a non-existent family. But at that point the Puppet Master is still under the control of its human creators. It’s the members of Section 6, handling foreign affairs, who are using the Puppet Master in a horrendously cynical game to ensure the deportation of an exiled Colonel, in a subplot so oblique that viewers may not register it at all.

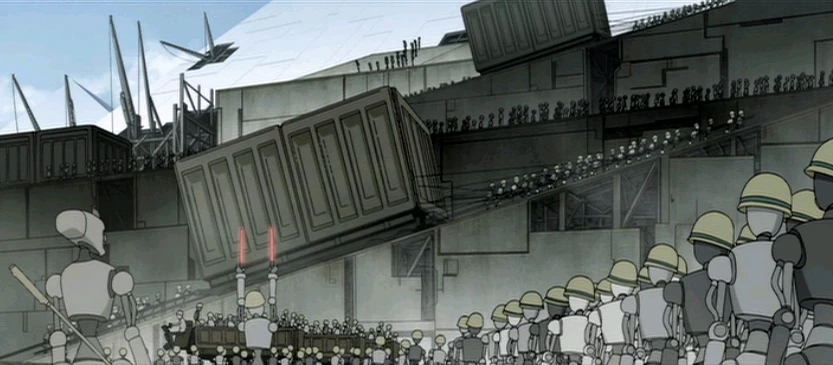

This theme of A.I. victimhood goes back to Astro Boy, where robots are depicted as an oppressed and abused minority. Western fans, though, are likelier to think of the spectacular “Second Renaissance” segment of The Animatrix. Its story of a robots’ revolt is dazzlingly-illustrated pulp, put on another level by its resolutely doom-laden tone and its fusing of religious-apocalyptic imagery and grim real-world references (Vietnam, Tiananmen Square). Mahiro Maeda directed the segment shortly before taking on Gankutsuou: The Count of Monte Cristo.

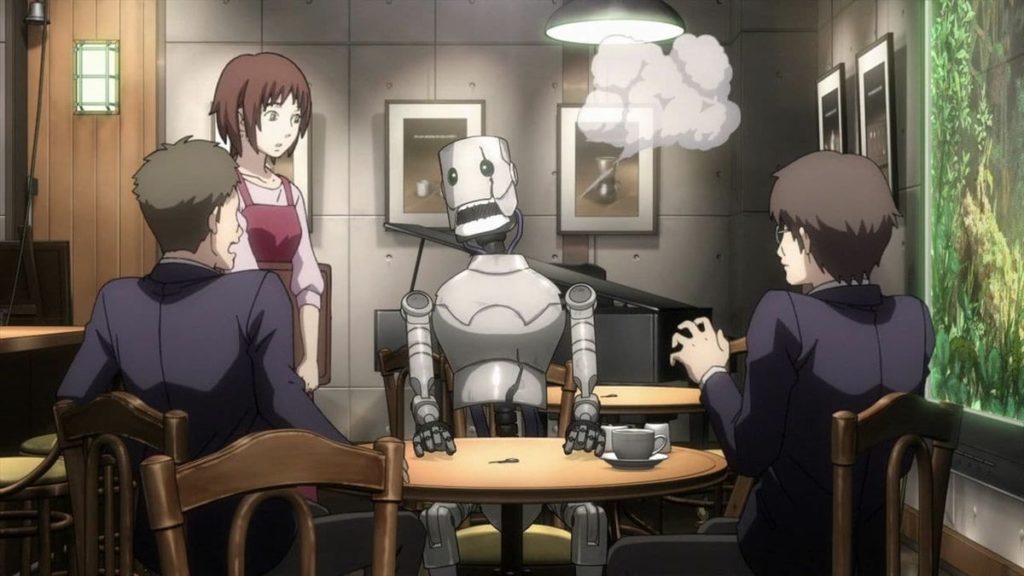

However, there are far rosier visions of human and robot coexistence. In Yasuhiro Yoshiura’s Time of Eve, humans and androids socialise in a genteel café, seeking mutual understanding. In the series Plastic Memories, androids can be beloved members of a human family, with none of the psycho-horror tensions of Spielberg’s A.I.: Artificial Intelligence. The snag is these androids have far shorter lives than humans, and they can succumb to a violent kind of mechanical Alzheimers – which of course makes them seem all the more human. Anime being anime, there are also series with androids as hyper-cute, loyal girlfriends, as in CLAMP’s Chobits and Gainax’s Mahoromatic.

A different angle, going back to Astro Boy, is of the A.I. android created in the image of a human loved one. Astro Boy’s origin story involves a scientist who’s broken by the death of his human son, Tobio, in a car crash. The scientist creates Astro Boy in his grief, even though he rejects his creation. Studio Wit’s 2013 film Hal develops the idea; its android is the double of a deceased loved one, not as a dastardly trick, but as part of an official programme of emotional therapy. (It parallels a British film released the same year – the acclaimed “Be Right Back” episode of Britain’s Black Mirror.) Steins;Gate 0, the ‘what-if” sequel to the first Steins;Gate, confines its A.I. simulation of a dead girl to a screen, but that’s enough to move the hero to tears.

There are also maternal A.I. characters. Mecha can have the “minds” of mothers, as any Evangelion fan knows, though that anime’s only clearly A.I. character is the MAGI computer system. Studio Polygon’s Pacific Rim: The Black has a hero robot with its own A.I. “mind,” called Loa, which speaks in a female voice and becomes increasingly maternal towards the youngsters it guides. In the delightful film Sing a Bit of Harmony, the sailor-suited singing android Shion looks like a schoolgirl but she, too, becomes more and more of a mother to the heroine, especially when her extraordinary secret origins are revealed.

The notion of maternal relations between human and A.I. characters is taken still further in Tezuka’s 1980 film Space Firebird 2772. In its extended wordless prologue, accompanied by lush music, a human child is born from a tube and raised entirely by machines. Eventually he’s presented with a large metal capsule which unfolds to become a beautiful blond woman, his new mother. What’s striking is that this character, Olga, is shown as a robot from the very start, both to us and the child. In contrast to the Terminator, he and we see her metal skull before it’s hidden by her lovely face. At the touch of a button, Olga can change form again, becoming any number of non-human shapes. Some of the permutations are faintly pornographic.

Space Firebird’s main story involves a strange union between human, A.I. and a cosmic spirit. Olga starts falling in love with her now adult human charge, Godo. However, Olga is destroyed during Godo’s interstellar hunt for the titular Firebird, an immortal, mystical being. But the Firebird falls for Godo in turn and possesses Olga’s body. She and Godo become quasi-incestuous lovers. At the end, Godo returns to a dying Earth, realises Olga is possessed, and begs the Firebird to let him die, as the price for Earth to be restored. The Firebird separates from Olga and grants Godo’s wish. As a last favour, she resurrects Olga and Godo as a human mother and baby.

It reflects how much anime seems determined to break down distinctions between human and A.I. altogether. Readers may notice that the summary above has affinities with Ghost in the Shell, and its relationship between the Puppet Master and the Major Kusanagi. Officially, Kusanagi is not an A.I. She’s a cyborg, who was born human and given technical augmentations. But there’s a telling scene in the film, when Kusanagi learns about the Puppet Master and doubts her own origin. What if Kusanagi is actually an A.I. who thinks she’s human, like the replicant Rachael (and maybe others) in Hollywood’s Blade Runner?

It recalls the puzzle of the Chinese philosopher Zhuangzi; was he a man dreaming he was a butterfly, or was he a butterfly dreaming he was a man? The same ambiguity underpins the underrated CG film version of Astro Boy in 2009 (which isn’t actually an anime, as it was made by Hong Kong’s Imagi Animation Studios). This version tweaks Astro Boy’s origin by having the robot implanted with a dead boy’s memories, raising questions that have vexed philosophers. Could such a being qualify as being the “same” person as the original (especially as there’s no living competitor for the title)? Or is he just a robot deluded into thinking he was born human?

Other anime have A.I. minds that are “based” on human ones, as per the transhumanist assumption that you can copy a human’s memories and consciousness and turn them into purely digital phenomena, like Max Headroom or Red Dwarf’s holograms. The virtual pop star Sharon Apple in Macross Plus is a classic anime case. “Born” from the brain waves of a troubled woman, she becomes that woman’s doppelganger and nemesis. Macross Plus is a psycho-thriller like Perfect Blue but with an extra A.I. framing.

It’s left open if Eva, the phantom of the (space) opera in the “Magnetic Rose” segment of Memories was created in a similar way. Otherwise, it’s an A.I. with a Norman Bates delusion – one of the story’s last shots suggests Psycho. A similar idea is suggested in a key scene in End of Evangelion, involving the MAGI computer system mentioned earlier. Roujin Z suggests a more romantic version of the idea. A robotised bed builds an A.I. from its geriatric occupant’s loving memories of his late wife, and concludes it is his wife.

Other anime A.I.s range across the map. There is the mischievous, childlike, beaming Doraemon – remember this children’s character, who’s often seen as Japan’s Mickey Mouse, is also an A.I. Just as loveable are the virtual animals which children command in Mitsuou Iso’s brilliant 2007 series Denno Coil, ranging from a dog to a dinosaur. Neither robots nor mere screen presences, these creatures are overlaid on the “real” world via the children’s cyber-glasses, in an anime made years before Pokemon Go.

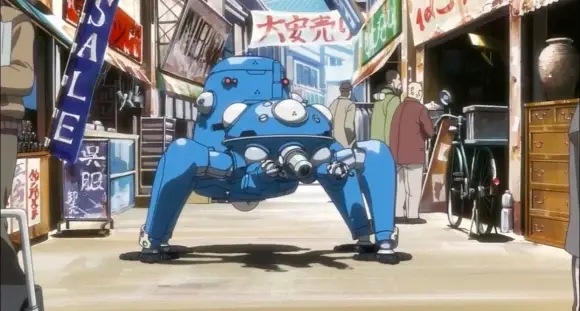

The A.I.s in the Stand Alone Complex TV version of Ghost in the Shell suggest animals and children. These are the beetle-like Tachikoma robots, who speak in piping voices like J-pop idols, and are shown eagerly debating the theories of James Lovelock or Richard Dawkins, when they’re not snuggling puppyishly up to their masters. Shockingly, during the first SAC season, Kusanagi decides these endearing creatures must be destroyed as they’re becoming too independent-minded – an argument with great resonance in 2023. However, the Tachikoma are better survivors than cockroaches.

But I’ll round off this survey of A.I. in anime with the towering, swaying robots in Miyazaki’s Laputa: Castle in the Sky, which are presumably A.I. creatures. When they’re ordered to destroy by their evil human masters, they’re baleful and terrifying, like their relatives in Laputa’s acknowledged inspiration, the 1941 Superman cartoon, “The Mechanical Monsters.” But left to their own devices, the robots are gentle gardeners, friends to little animals and children alike. They evoke the stumpy droid Dewey in the American SF film Silent Running, tending to the last forest from Earth as it floats in space. It has no interest in destroying humanity; we’re doing a good enough job at that ourselves.

Andrew Osmond is a thinking machine, programmed to believe that he is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films.

[ad_2]