[ad_1]

June 4, 2022

·

0 comments

By Jeannette Ng.

Despite the assumptions encouraged by the title, Emma: A Victorian Romance is very much not based on Jane Austen’s Emma. However, its literary ancestors are manifold and those with familiarity with Victorian novels would find themselves passingly busy noting the connections. Emma overhears a whispered discussion about a scandalous yet delicious novel about transgressive love in Mudie’s Lending Library. After the events of the end of season one, Emma travels to Haworth in Yorkshire, known for its strong association with the Brontës. The fire at the Mölders estate, Emma’s principled rejection of William as well as a madwoman kept secret from society both evoke Jane Eyre, though of course Aurelia Jones is far better treated than the first Mrs Rochester ever was. Aurelia’s alias, Mrs Trollope, is also an allusion to the novelist Anthony Trollope. Aubrey Beardsley and his art are discussed by William and his siblings, with Hakim invoking Aestheticism’s rejection of social norms to persuade William to discard his sense of familial and societal duty.

Emma plays out its romance with restraint and realism. It is so firmly grounded in its Victorian world, so carefully vivid in its details and sketches its characters with such intimate delicacy that it is sometimes easy to forget how ingrained the trope that sits at its heart is. For all that it does spawn a passionate fandom with cosplayers and a themed café, the anime Emma feels oceans apart from the world of maid cafés, burlesque acts involving feather dusters and double entendres in a French accent.

Despite how little time “bonnets and bustles” most historical dramas have for the hired help — Netflix’s Bridgerton treats them basically as furniture – the maidservant as a focal point of sexual and erotic fascination has a very long and lurid history. Published in 1740, Samuel Richardson’s Pamela; or Virtue Rewarded details the various entanglements between the titular Pamela, an innocent maid and the rapacious Mr B, her employer. Pamela’s passionate defence of her own virtue is indeed rewarded in the reformation of Mr B, who no longer seeks to make her his mistress but marries her and elevates her in society, though this change in status brings with it tribulations of its own. The Aesthetic and Decadent movements in the early 20th century brought with it yet more erotic depictions of maidservants, including Octave Mirbeau’s Diary of a Chambermaid.

Japanese art has obviously also latched onto the archetype, but she does diverge in substance as instead of a fashionable, flirtatious lady’s maid or a specifically French coquette, she becomes a caring, competent and loyal figure. Recent examples include Hanako Kujo from Goodbye, My Rose Garden and Rae Taylor in I’m in Love with the Villainess. Kyoto Animation’s Miss Kobayashi’s Dragon Maid even contains within it a potted history of the maidservant and the evolution of her uniform as expounded by the main character. The maid outfit of frilly apron and cap has itself become a shorthand to signify and invoke demure, domestic femininity, often given as costume to a deadly assassins, hardened fighters and loyal bodyguards for that extra edge of contrast.

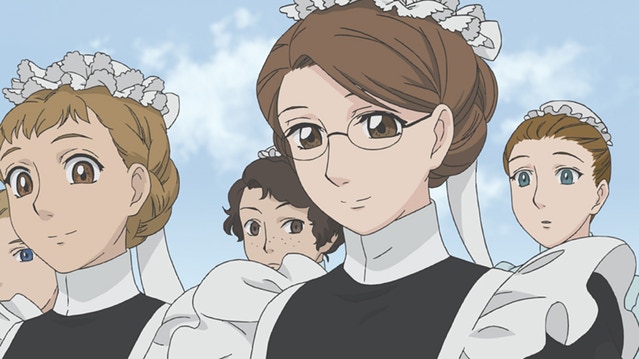

It is possible to see shadows of these myriad maidservants in the character of Emma, but she also stands apart from many of them. The setting firmly the rejects fetishistic flourishes and conventional pandering, favouring a restrained romanticism in depicting the intimate emotional layers of a very private, often passive character. Blushes intrude upon her impeccable façade and. Fleetingly. we are invited to glimpse behind her measured elegance when she loosens her hair and indulges in a novel of scandalous, transgressive, class-defying love. Hers is a quiet strength that endures without complaint. She has very little control over her own life and is often subject to the whims of her employers, however kind and considerate they may often be; it is Kelly Stownar who notices Emma’s need for a pair glasses and gifts them to her. But at the same time, Emma has no choice but to remain silent as William’s father details to Kelly Stownar his plans to marry William off. Nor can she say no when Dorothea Mölders orders her to accompany Aurelia Jones to her son’s engagement.

Emma feels deeply but allows little of it show, becoming only more private after her heartbreak at the end of season one. Her coping mechanism is one of withdrawal. But it is in her sometimes-contradictory actions that she betrays her tumultuous sea of emotion. She both wants to return to London and be near William again, yet at the same time desperately needs to stay away.

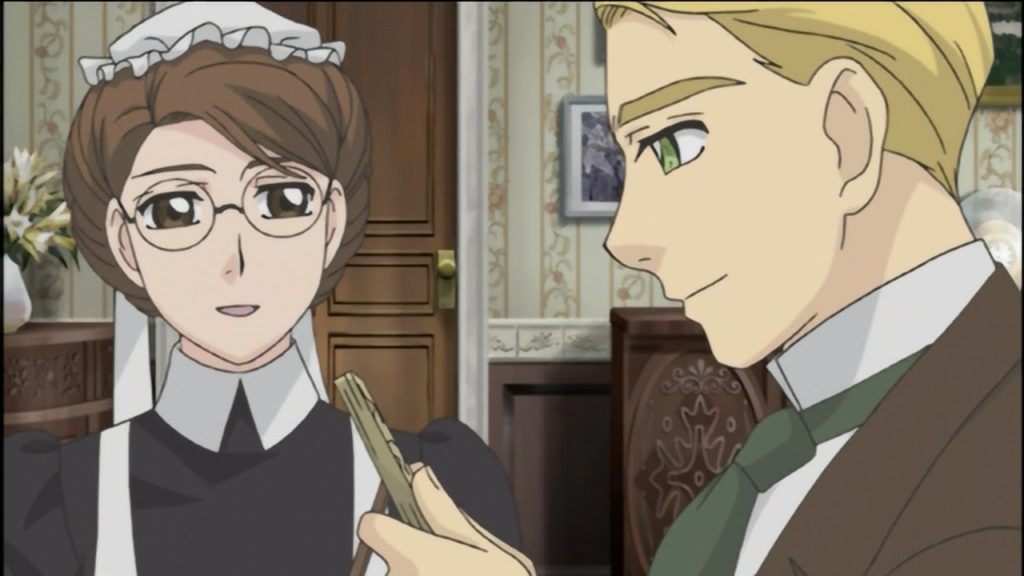

As character study, Emma excels in the depiction of small, intimate moments, not just a hesitant glance or a wavering smile, but also the details of dressing and undressing, those masks of uniform and propriety. Emma’s spectacles, as well as her hair and its various states of tidiness take on emotional significance. None of this is to say that, Emma is an anime without poetic monologues and emotional declamations that lay bare the souls of their characters. There are those aplenty, especially beneath moody skies and generally sympathetic weather. Hans in particular has a memorable one in which he shares the childhood that shaped him. But even in these speeches, it is what is left unsaid that lingers.

William is unrelentingly earnest and often oblivious. Unlike the majority of his literary and even real-life counterparts, his interest in Emma does not dwell on her working-class earthiness, her seeming subservience or even her frilly attire. The two of them are certainly not Hannah Cullwick and Arthur Munby — though one can easily imagine Cullwick and Munby in an anime, albeit a considerably kinkier one.

Theirs is a romance of stolen moments and in-between conversations. It is nurtured in an ever-liminal half-light, but it is also in the Crystal Palace, that ostentatious symbol of Victorian futurism (also glimpsed in Katsuhiro Otomo’s Steamboy) where Emma and William share their first kiss. Locked in by accident at the end of tentative date, the two finally speak their true feelings. The story positions their love as part of that optimistic, hopeful future that the Crystal Palace promises in its exhibitions, that sense of progress and possibility. They are not out of time, but fundamentally grounded within it.

Hakim’s invitation to spirit the married Lady Mildrake away from all this tedious London society also takes place in a rosy half-light, when both are expected elsewhere. The exact nature of their relationship — be it simply friendship or something more — is never quite clear, though both are clearly fascinated by the transgressive nature of their association.

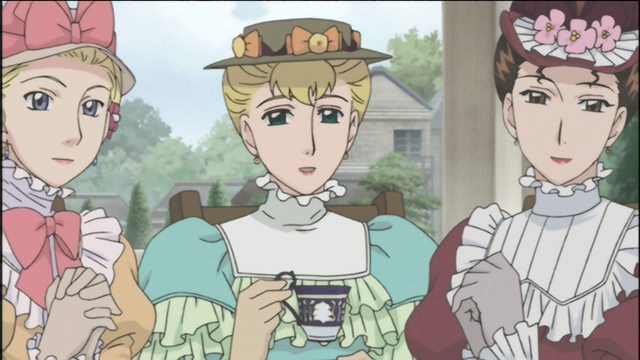

Throughout, the naive William is pitted against his father, a social climber keen to engineer for his son a marriage to the daughter of a cash-strapped viscount. As rich merchants seeking to become accepted among the gentry, the Jones are held to a much higher moral standard that those already born to privilege. William’s mother, Aurelia Jones, never names the ailment that drives her to live apart from her family, but it is clear that the polite society of London was anything but polite to her. The same circles whisper about William’s scandalous entanglements with the help behind his back.

Despite the carefully constructed verisimilitude, there is still a deep romanticism at the heart of Emma, one that yearns and aches and thinks more kindly of everyone than they entirely deserve. This is not the scathing portrait of society as penned by many a Victorian novelist. The manga in particular builds on this empathetic tone with side stories that are essentially character studies of the supporting cast.

Times are changing, no matter how much people like Viscount Campbell and Richard Jones want them not to be. The century turns, and what was unthinkable becomes almost normal. Victorian silhouettes give way to the elegant Edwardian one. The society in which Emma and William fell in love is not the one they must live in forever. The rigid structures of society remain, but they need to bend to fit the shape of the new era. It is how they fit into that changing world that makes them so easy to believe in as characters for me. Even as the story closes, I can imagine them living out lives in the shadow of history, optimistic and oblivious to all the suffering and strangeness that the new century will bring. But to paraphrase Kelly Stownar, I also want to believe they’ll be just fine.

Jeannette Ng is the author of Under the Pendulum Sun. Emma: A Victorian Romance is released in the UK by Anime Limited.

[ad_2]