[ad_1]

By Andrew Osmond.

Speaking about his anime film Magnetic Rose, part of the Katsuhiro Otomo-produced anthology Memories, director Koji Morimoto made a bold proclamation. “The characters in the story had to escape the magnetic field,” Morimoto said, “so Satoshi Kon and I used to say we had to escape the magnetic field called Otomo!” Kon was Magnetic Rose’s writer, two years before his own directorial debut with Perfect Blue. For both Kon and Morimoto, Magnetic Rose was a crucial stepping stone in their careers.

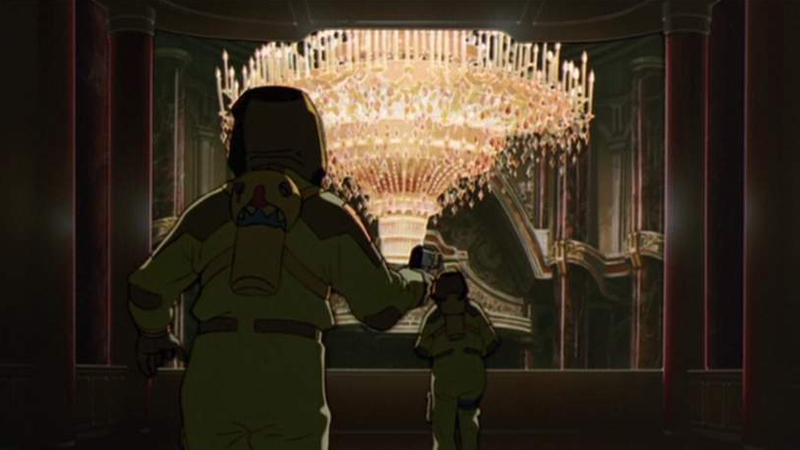

“Magnetic Rose” is a true space opera; much of the film takes place to the strains of Puccini’s Madame Butterfly. A team of space salvagers is drawn by an SOS message to a dangerous gravity well. Here they discover a bizarre metal edifice in the shape of a giant rose, made from the debris of countless wrecks. Two explorers find an entrance, and a giant opera house within, where there dwells a siren-like phantom.

The characters move through a vivid succession of increasingly Freudian spaces, starting with the transition from the male salvagers’ weightless ship into the female depths of the rose – the symbolism is obvious, witty and lovely. The palatial opera house inside the rose projects holograms of sun and flowers to hide the mucky swamps below.

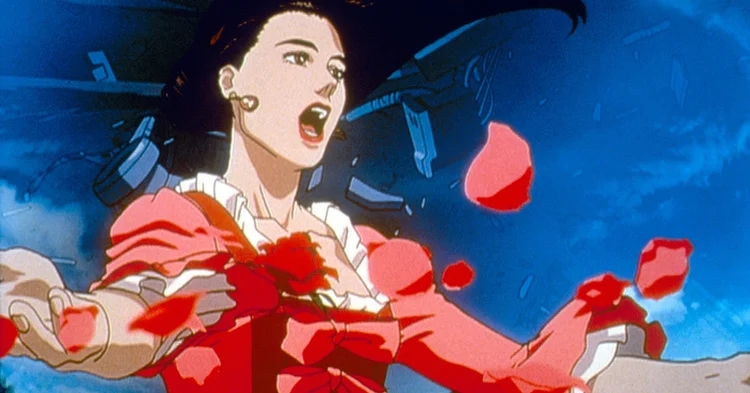

Yet this is no simple fable about a ghostly femme fatale. One of the siren’s male victims, Miguel, is a deluded and arrogant womaniser. Another of the characters, Heintz, is emotionally blocked, denying a tragedy that’s cruelly re-enacted for him as a stylised but heartrending performance. The final bells-and-whistles cataclysm sees the diva resplendent in her crimson gown, serenely singing Puccini in a maelstrom of wind and metal.

For fans of Satoshi Kon, Magnetic Rose’s shift into dreamlike and fantastical territory clearly anticipates his later work. The film is filled with sweepingly theatrical reality shifts and scene changes. At one point in the action, a whole house erupts from the ground. The operatic phantom foreshadows the ghost-Mima in Perfect Blue, and she also feels like an evil sister to Chiyoko in Millennium Actress, burning eternally for her lost love. The descent to the phantom’s dreamscape lair is a prototype for a similar sequence in Kon’s Paprika.

Also like Kon’s later features, Magnetic Rose blurs genres with tremendous skill. Two of its most obvious references are to Stanley Kubrick, to 2001 (classical music enhancing the starfields) and The Shining (a haunted giant building, though 2001 had its own hotel in space). The spacemen haunted by their earthly memories evoke the 1972 Russian film Solaris by Andrei Tarkovsky – Magnetic Rose predated the American remake by Steven Soderbergh. The anime also has heavy overtones of the first Alien by Ridley Scott.

However, Magnetic Rose’s direct source was a one-off strip written by Otomo, about thirty pages long. The manga was called, depending on how you want to push the translation “Thoughts of Her” or even “Her Memories” – indeed, of the three stories in the Memories anthology film, it’s the only one which actually deals with memories. Perhaps a third of Magnetic Rose’s anime story comes from Otomo’s strip. The manga has the salvagers encountering the metal rose in space, finding the opera house, and investigating the mystery of its owner, before mayhem breaks out in the last pages. However, the strip doesn’t have the film’s dreamlike transitions and singing ghosts, and its characters are ciphers. The characters of Miguel and Heintz were created for the film, along with Heintz’s whole backstory.

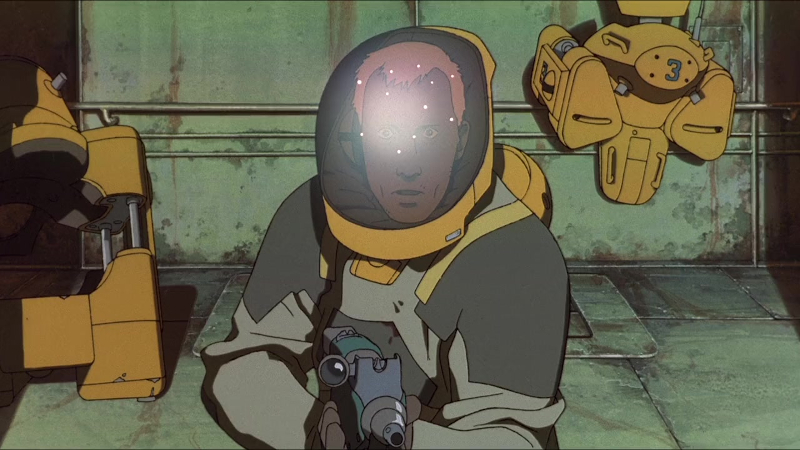

“We decided that people who go in there should also have a story and drama,” Morimoto said. “The protagonist is of course her, but we needed to place someone in contrast. That was how Heintz came about. The deeper he explores, the more he is seeking inside himself. The camera moves forward to investigate the situation. Although the protagonist does not walk, if a moving camera-perspective can convey that internal search, it would be interesting.”

Otomo’s manga was translated into English in the 1990s. There was a colourised version published as a stand-alone comic, called Katsuhiro Otomo’s Memories, with the cover tag, “Sci-Fi Drama in the Akira tradition,” published by Epic Comics, Akira’s American publisher. It was colourised by Steve Oliff, who had colourised Akira as well. In Britain, the strip was published in monochrome as part of a translated book collection of Otomo’s strips, just called simply Memories. Both these editions are rare today, so if you spot either, they’re worth snapping up.

Morimoto’s comments suggest that adapting the strip for the anime was a strongly collaborative process between himself and Kon. Kon, of course, is famed today for the clutter of his lived-in environments, but at least part of that impetus may have come from Morimoto, then his senior, who pushed his staff to put in background details that might be doomed to be overlooked, because he wanted to shoot the scenes as if they were real places, not sets to be admired. He demanded that: “these sets are for the shots, not shots to show off the sets.”

Otomo, too, recalls a production process in which the staff tried to visualise the locations as real places, a fact made easier by Takashi Watabe’s creation of a 3D computer environment for shooting in the spaceship. This, in turn, allowed for virtual cameras to be switched around and repositioned as if shooting in a real place, and as if using real lenses. Otomo recalled that he and the staff, particularly Kon, “…had a proper chat about which lens we might use when depicting each scene, and the size of each lens, such as telephoto, wide angle, and standard, and how a framing should have proper meaning. In that sense, I believe I am aware of the ‘camera’ very much when directing.

“For one scene, we used a telephoto, which means a shallow depth of field. That’s why the background is blurred, which makes the people stand out… Simple things like that can make for clear directing. Using a wide-angle lens, the focus is on both the background and the character, which can emphasise the environment that they are in.”

According to anime expert Benjamin Ettinger, Koji Morimoto’s “work in this period was realistic and captivating, characterised by attention to small details that no other animator would notice.” By the late 1980s, Morimoto was Assistant Chief Animator on Otomo’s Akira, a film which suffered heavy production delays that called for emergency assistance. In the sort of pitching-in that remains touchingly commonplace in the anime business, Eiko Tanaka, then a line producer at Studio Ghibli, drafted some of her staff to help out. Morimoto later repaid the favour by sending some of his own people to help Kiki’s Delivery Service hit its deadlines, by which time he and Tanaka were already going into business together, as the founders of Studio 4°C.

For Memories, Morimoto said he pushed to adapt one of two Otomo strips. One was “Memories” and the other was a strip called “Farewell to Weapons.” The latter was a soldiers-versus-mecha piece; it didn’t get into the Memories film, but it would be adapted two decades later as part of the anthology Short Peace, directed by Hajime Katoki. Morimoto also chose the composer who’d need to complement the music of Puccini. He picked Yoko Kanno, having worked with her when he created the concert scenes for Macross Plus a year before. Magnetic Rose was one of Kanno’s first anime credits, in a similar classical vein to her work on Vision on Escaflowne soon after.

“Morimoto wanted a normal opera to be broken and disrupted using a computer synthesiser,” Otomo recalled. “Just as the heroine Eva is breaking down, so is the classical music. But at the suggestion of Yoko Kanno, we went for more orthodox opera in the end.

“Originally, I was against the idea of using Madame Butterfly,” he added. “It is too famously Japan-related and has orientalist elements, you know. That niggled at me, and I wanted to use a piece that fewer people had heard of. So, I bought opera books and scoured through lyrics in translation, but in the end, I thought [Puccini] was the right decision… We went to the Czech Republic and recorded at Dvořák Hall, and it felt lovely. The only audience was us, so we had all the place to ourselves!”

In 1997, composer Kanno would find true fame with her acclaimed music for another space anime, Cowboy Bebop. Coincidentally, the Japanese voice cast for Magnetic Rose includes Koichi Yamadera, the future Spike Spiegel, voicing the womanising Miguel. Moreover, the phantom Eva in Magnetic Rose is voiced by Gara Takashima, who would soon voice Cowboy Bebop’s star-crossed Julia. In an unlikely moment of musical fan-fiction, the story of Eva would be retold from the perspective of her lover Carlo, in Robbie Williams’ 2002 song “Berliner Star.”

Magnetic Rose was a launchpad for two future anime celebrities, Satoshi Kon and Yoko Kanno. For Morimoto, it was an opportunity to put the studio he had co-founded on the map. After Magnetic Rose, Studio 4°C’s work would quickly blossom, through prestigious titles such as Mind Game, Tekkonkinkreet and the Berserk film trilogy. The studio’s recent cinema films include the dazzling Children of the Sea and Fortune Favours Lady Nikuko. 4°C also followed up Memories with further anthology work for The Animatrix and Genius Party.

According to Benjamin Ettinger, after Akira, Morimoto “started seeing things more as a director than an animator; he started to feel the animation should be subordinate to the directing and not vice versa.” He also became critical of the style adopted by Otomo in his Akira anime, despite Morimoto’s own sterling work on the film.

So, it’s hugely ironic that the first thing many viewers will notice on seeing Magnetic Rose is how massively Otomo-ish it feels, especially with its highly “dimensional”, space-filling characters a la Akira. Indeed, viewers who didn’t check the credits might easily assume that that Otomo directed Magnetic Rose, not Morimoto. It was only in later years that Morimoto could express himself in more symbolic, freeform projects, such as his 1997 short Noiseman Sound Insect and his Genius Party segment, “Dimension Bomb.” By then, he had finally escaped Otomo’s Magnetic Rose.

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films. Katsuhiro Otomo’s Memories is available to pre-order from Anime Limited.

[ad_2]