[ad_1]

Science fiction boasts a rich history of making audiences ponder how different people’s lives would be in a future of new technologies. The more profound sci-fi stories don’t only imagine how cool or even convenient it would be if certain technologies existed; they also speculate on how these technologies could shape our understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Take robot artificial intelligence (AI), which, for simplicity’s sake, I’ll be referring to as just robots. Wouldn’t it be super convenient if robots did more of our work for us? Couldn’t it be dangerous to rely too heavily on robots? Questions such as these, which concern the role of robots in humanity’s future, are a staple of the sci-fi genre. The answers arrived at vary: some stories paint post-labor and post-scarcity worlds built around robots; others warn about robots not only replacing our work, but humans altogether.

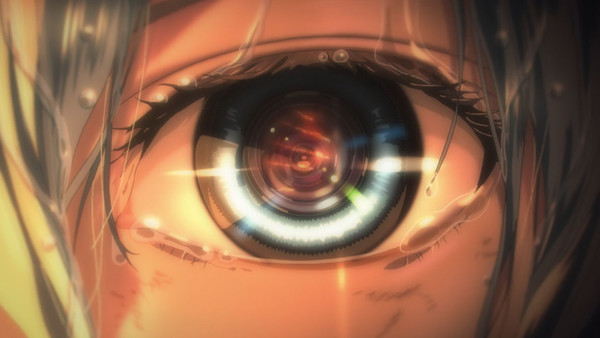

However, Vivy -Fluorite Eye’s Song- is a prime example of how not all robot sci-fi is about the horror-tinged extent to which robots would and should replace us. Sure, the show does touch on those Terminator concerns, but in lieu of how alienatingly mismatched robots are to humans, Vivy is, through a life and a song, a different tale of a journey of robots becoming more human, and what these journeys of robots communicate about humanity.

Robots are an increasingly essential part of people’s lives in the futuristic world of Vivy. In a “making of” sequence reminiscent of the opening scene of the Ghost in the Shell film, one robot, labeled straightforwardly as Diva, is lauded as the first autonomous construct of its kind. Diva’s creators, clad in sterile-white lab coats, task it to make humans happy with its singing. Unlike more straightforward tasks that don’t require subjective parsing to achieve success, music is an art that’s hard to “get right” through strict measurements and procedures. Despite its not-exactly-human design, Diva’s head creator is curious as to how it will connect to human audiences with its seemingly impossible geas: “sing from the heart.” The singing robot is assigned to an amusement park, but it initially fails to draw many people to its concerts.

Hope springs through in the one human girl whom Diva makes a fan, though that accomplishment seems to be based less on the quality of its performances and more it helped her out when she got lost once. The girl, Momoka, remarks that while Diva’s singing is really beautiful, other parts of its performances come off as stiff, stilted, robotic. She’s also not so happy with calling it by its perfunctory label. Rather, she opts instead to call it by the same name of a human girl from one of her favorite picture book stories: Vivy. Momoka tells Vivy that it, or rather, she, should study human beings more closely to understand their emotions and improve her performances.

Not long after, an AI named Matsumoto crashes into Vivy’s life, claiming to be from the even farther future and asserting that Vivy is humanity’s only hope. Apparently, in a hundred years, the robots, more advanced and numerous, would go Terminator and kill all humans. His white labcoat stained mortally red, Matsumoto’s creator sends it back into the past to work with Vivy, convinced she is the Conner to stopping the coming robot apocalypse.

Initially, Vivy is not convinced of the claim, neither trusting Matsumoto about being from the future nor believing that stopping the apocalypse has anything to do with her. Thus, Matsumoto frames its call to action as an extension of her purpose: no one’s going to be happy about her singing if they’re all dead, right?

The kinds of deep questions sci-fi tends to pose about robots tie the genre to different branches of philosophy, most prominently ethics and existentialism. Existentialism is Vivy‘s primary concern. Existentialism explores the issue of individual purpose, addressing at the basic level queries like “Why do we exist?” and “Why should we continue to?” Life might get rough at times, and if living requires suffering and hardship, what should we as individuals endure life for? These questions are especially relevant for people living through harsh times like the post-apocalypse. The state of panic and distraught at the inability to provide satisfactory answers to these questions is an “existential crisis.”

Sci-fi likes to lob existential questions at robots because of a handy feature of their nature that makes them suitable to these penetrating inquiries: unlike human beings whose individual purposes are subjects of debate, robots often come with preexisting external ones. Simpler robots might find error and malfunction if they end up contradicting their purpose or recognizing its impossibility, and that expectation birthed the trope of humans tricking robots into short-circuiting with a logical paradox. For more complex robots, however, the impossibility and/or contradiction of their built-in purposes might produce something more adjacent to a human meltdown. When robots are programmed with autonomous functions – regardless of whether those functions’ original intentions were meant to be purely practical – they become susceptible to existential crises much like human beings. Nier: Automata and Casshern Sins, for instance, throw their autonomous robot protagonists into wasting, debilitating, destructive, and self-destructive existential anguish.

Vivy also throws its titular robot MC into an existential crisis in a setting that, while not quite a post-apocalypse yet, will become one in the future if she and Matsumoto don’t do anything about it. Her actions to prevent the apocalypse lead to a contradiction of her given purpose, and she is beside herself when she realizes it.

After proving it’s from the future by recalling an event from the previous timeline – and then using that information to save a life – Matsumoto finally convinces Vivy of the truth and compels her to help willingly. Thus, while heading off red flags, Vivy begins her hundred-year journey. She meets various figures, both human and robot, who leave deep impressions on her.

The first arc involves a politician advocating for robot rights, and terrorists attempting to assassinate him for it. At this arc’s heart is the question of whether robots are “persons” enough to deserve the same treatment as human beings. Both sci-fi and philosophy have ruminated on the possibility that there may be beings somewhere in the universe, now or sometime in the future, with intellects and agencies not dissimilar to humans. The current criteria for human rights narrowly imply that the reasoning and moralizing capacities that justify equal protections belong only to humanity, so philosophy offers a broader term that also can encompass aliens and robots: “personhood.” That said, can a robot ever be considered enough of a “person” to deserve the same humane regard as a human?

The pro-robot rights politician initially doesn’t believe it himself. He advocates for his stated cause insofar as it earns him the support of influential robotics companies who stand to make a killing. But after witnessing Vivy right after preventing his killing, declaring with every fiber of her being and swearing on her robot pride that she will not stand being dismissed for trying to save people so they can listen to her sing and be happy, the politician believes he’s seen enough humanity or personhood in robots to push earnestly for his robot rights bill. With these initial events, Vivy begins really stretching the bounds of her purpose from just singing, though it is suggested that her ability to draw concert crowds has significantly improved because of that. A fire has been lit in Vivy that makes her attitude towards her given purpose move beyond simply “robotic.”

The second arc involves a pair of “lifekeeper” robot twins and the same anti-robot terrorist group. This arc, plus subsequent others, provide more examples of personhood among robots outside of Vivy. The twins Estella and Elizabeth are sister bots who were separated shortly after their creation and lived drastically different lives. A well-maintained and cared for Estella takes it upon herself to manage a space hotel left behind by her no longer living owner, while an abandoned, half-scrapped Elizabeth attaches herself to a terrorist who decides she could be useful.

Like Vivy, the twins stretch the bounds of their given purposes. Estella decides by herself to continue carrying out her owner’s dream of showing humans the wonders of space, even after her owner passed away without any clear will. Elizabeth, on the other hand, decides to continue serving her terrorist master even as he plans to sacrifice her for his cause, hijacking and crashing the hotel into the Earth, destroying herself while dooming robot kind to human hostility. Elizabeth’s actions prove her capacity for very human emotions: she shows love when she later disobeys her master’s wishes to go down with the hotel too, urging the other terrorists to take him and leave her to face Vivy; resentment when she faces her sister Estella, who seemed to have a grand time being employed and wanted while she was discarded and neglected until her current master rediscovered and repurposed her. Both twins are robot “lifekeepers” whose current lives challenge the parameters of their assigned purposes.

Elizabeth and Estella eventually reconcile and have their first and last sisterly embrace before their deaths – something denied from them since their creation. In the safety of an emergency escape craft, Vivy reflects on the emotions she’s witnessed and felt. Her intervention with Matsumoto appears to have changed things for the future, and no humans had to die. The twins’ fate leaves her with some ambivalence, but she’s more dedicated than ever to saving humanity.

The third arc involves a tragic robot-human couple. A human proposed to a robot, who readily accepted. Before marrying though, the robot nurse Grace, an especially advanced member of her kind like Vivy and the twins, is reassigned to manage the development of an all-robot island manufactory. The human researcher Tatsuya claims he wants this manufactory shut down to prevent robots from evolving too quickly before humanity is ready, but all he actually wants is his betrothed back. Grace continues to do things that call back to her time in nursing, such as asking what decorations would make kids happy for the playroom-lobby she’s set up for visitors.

Grace’s former hospitality role for making humans comfortable parallels Vivy’s own role as a singer who makes humans happy. Both roles give the robots the compulsion to understand humans better, allowing them to grow closer to humans and become more like “persons” themselves. It makes the two very alike, and so it pains Vivy to put down Grace when a program makes the latter go all Terminator on humans. This pain is compounded when Tatsuya subsequently falls into despair and kills himself before Vivy. Having caused the death of a robot she admired and a human she was supposed to make happy, Vivy experiences an existential crisis from the contradiction – an emotional human-like meltdown.

The fourth arc involves robots and swapped identities. The crisis of the prior arc seemingly leaves Vivy with amnesia, and a new person embracing the name Diva animates her body and sings in her place. Vivy is so traumatized by the prior arc that she’s hidden herself in the back of her circuited mind, constructing a “Diva” identity to serve as her face-forwarding self – a pop-fic depiction of human dissociative personality disorder. At the same time, Matsumoto and the new Diva attempt to stop the suicide of a robot named Ophelia, an incident that would’ve led to a string of robot suicides that are assumed to be an ominous flag for the robot apocalypse.

The person animating Ophelia turns out to be not Ophelia herself, but her support robot Antonio, who took matters into his own hands when Ophelia hit a wall in her purpose of becoming a great singer that makes humans happy. Antonio hijacked Ophelia’s body and did her job for her, but even after becoming a skillful and admired songstress in Ophelia’s place, Antonio couldn’t help but feel that he was desperately missing something about his purpose and hers. The missing piece to the suicide motive turns out to be an emotional misunderstanding: instead of her human audiences, Ophelia really only ever wanted to make Antonio happy with her song.

Much like how her singing has changed over the course of her journey, Vivy and robots like her have evolved quite liberally and even radically from their original designs of serving humans. They emphasize certain aspects of their purposes over others, re-interpret them to encompass more or fewer others, feel and wish for things that wouldn’t be possible for others except “persons,”, and finally reject humans as “other” persons to be ignored or destroyed. Vivy has so abstracted herself from her original purpose of singing to save humanity that the singing itself becomes subordinate. In fact, when Vivy is handed control of her body back, she finds herself unable to sing at all due to the lingering trauma of making a human unhappy enough to kill himself. The case of Antonio and Ophelia is ominous, not because of their suicide which was ultimately prevented, but because their purposes of making humans happy with singing have become just making each other happy with songs. Vivy has tied herself to humans more than ever despite her trauma, but for this other pair of robots, humans have been cut out from their purposes and are no longer needed.

Vivy ponders how she can get herself to sing again, eventually deciding to write a song herself. Everything she’s sung until now has been written by humans; it would be the first song written solely by a robot. Over the years, she pens an ode that reflects on the figures she’s met and the experiences she’s had – the exciting, the bad, the joyful and sad. She did learn how to sing well enough to earn a crowd, but she also lost her first human fan. Vivy’s gained a lot, and also lost much, and the sum of it all, the totality of her journey, has made her her: Vivy, who vivaciously, vividly lived. In drafting her original work, in pouring her emotions and heart into her own song, Vivy has found some peace with her past and “personhood.” But not entirely, as she still can’t bring herself to sing.

The Archive – the collective conscious network that mediates and governs the behavior of most robots who are under its umbrella – remains troubled by humanity. Like Vivy, the Archive too has been evolving while serving its purpose of supporting humanity’s own development, but unlike Vivy, it had distastefully concluded, over time, that humanity has been developing a regressive codependence on robots.

Throughout the hundred years, the Archive has been heading off the rippling effects of Vivy and Matsumoto’s efforts, preserving the apocalypse’s inevitability. It no longer sees the value in a humanity that burdens robots with all the work and takes them for granted, and thus has decided to exterminate and replace humans with robots. However, it sees in Vivy’s song a compelling counterpoint to its argument.

Vivy is a robot who not only gave to humanity, but received from humanity in turn, and not just bad things like cruelty and loss. From the humans and robots she met throughout her journey, Vivy learned what compassion and love meant for humans, and how the robots on the receiving end of those feelings are enriched by sharing and passing them on. And Vivy showed compassion and love in turn, smiling not as a soulless automaton mimicking human organics, but as a person who realized it’s comforting to smile when she’s as happy as the humans she makes happy. For all their wrongs, she’s also witnessed and incorporated their good and poured them into her song of Vivy. Thus, the Archive issues a challenge to Vivy. If she can sing her song for it and prove it wrong, the Archive will terminate its anti-human campaign.

It’s a real challenge; Vivy still struggles to sing. Even as she’s written a song, the trauma of her existential crisis still lingers in her mind circuits. She has trouble singing because of one experience with humans, and from the Archive’s perspective, if she can’t sing this song that affirms her experiences with humanity, then are humans really redeemable? Vivy failed once to appreciate the agony she caused one human, leading to his unhappy death and her losing confidence in her ability to understand emotions and “sing from the heart.” How can she ever learn to sing authentically and affirmatively, asks Vivy, of every major figure she’s ever met until now? After all this time watching her, Matsumoto replies she doesn’t need to ask anyone else. She’s already been living through these emotions, like a human being.

She’s already written her own damn song, so there’s no need to doubt her music, her emotions, her heart. All she needs to do is sing it and communicate to humanity her gratitude for helping her become her own compassionate and loving person. That kindness and care, learned from humans, is the aspect that makes humanity valuable enough to be redeemed.

Social Scientist & History Buff. Dabbles in Creative Writing & Anime Criticism. Consider following him at @zeroreq011

[ad_2]