[ad_1]

By Tom Wilmot.

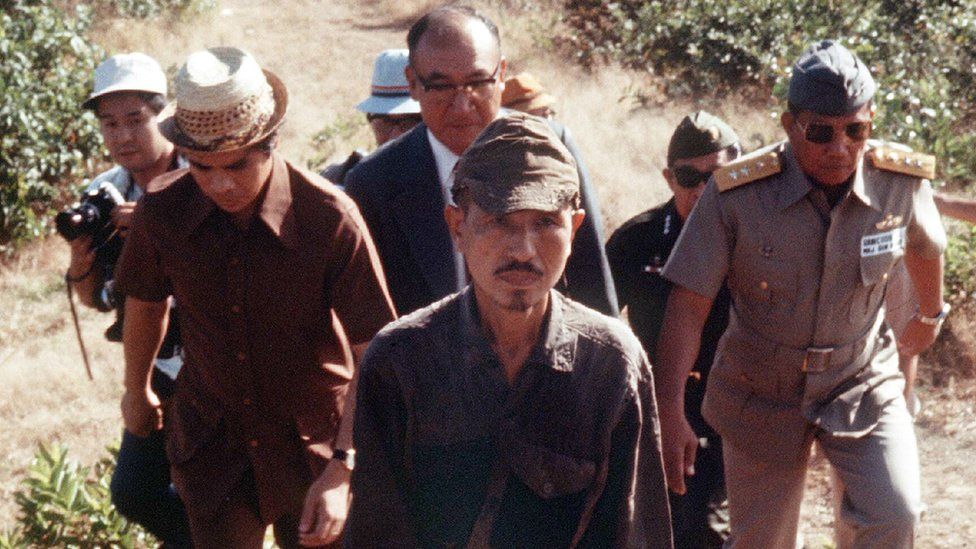

Nearly fifty years after he re-emerged from the jungle, Lieutenant Hiroo Onoda remains a fascinating and controversial figure. The World War II soldier famously surrendered in 1974, having held out on the small Filipino island of Lubang for the better part of thirty years, convinced that Japan’s conflict with the Allies was ongoing. Formally declared dead in 1959, Onoda instead raged a guerrilla war that saw up to fifty islanders and two of his comrades killed.

Revered in Japan as a hero upon his return, many still view the soldier as an embodiment of misguided Japanese imperialism. At the heart of Onoda’s unbelievable tale are extreme examples of human endurance, delusion, and desperation. Why fight for so long? What was it worth? It’s these questions that filmmaker Arthur Harari explores in the French-produced Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle.

Born in 1922, Onoda spent his formative years living in a militaristic Japan hellbent on the conquest of East Asia. From the ashes of the isolationist Tokugawa regime rose an industrial war machine driven by rapid modernisation and aggressive military expansion. Cultivating a populace in support of militarism was at the heart of the Japanese government’s imperialistic ambitions, with the country gearing up for an all-out conflict with the Western powers long before the Pacific War began in December 1941.

The propaganda machine of the 1930s and 40s saw the increased suppression of leftist politics, not in the least through substantial interference in the thriving film industry. The ‘Film Law’ of 1939 gave the State complete control over the industry, while many filmmakers, including Tomu Uchida and Kenji Mizoguchi, were sent to the southern colonies and Manchukuo to produce propaganda pieces. Military-focussed movies stressed the courageous struggles of the Imperial Army and championed unwavering loyalty to the emperor. Such propaganda even gave birth to Japan’s first feature-length animated film,Momotaro, Sacred Sailors (1945), a Navy-funded project intended to inspire a fighting spirit in the nation’s youth.

Onoda enjoyed the long reach of the Japanese Empire, spending a few years in occupied Hankow, now Wuhan, China, boozing and dancing before inevitably being drafted. After initially being taught that, as per General Tojo’s Field Service Code, he’d be better to die than live in shame as a prisoner, the young Onoda was re-assigned to the Nakano Military School in Futamata, where he was trained in the art of sustained guerrilla warfare. “You are absolutely forbidden to die by your own hand”, was the order barked at Onoda before he was deployed to Lubang, journeying with the belief that his superiors would return for him one day, whatever happened.

Mere months after emerging from the jungle, Onoda’s account of the preceding three decades was published in remarkably vivid detail in the aptly titled No Surrender: My Thirty-Year War. Not long after arriving on the island of Lubang in December 1944, the young Lieutenant found himself at the mercy of an American invasion that left him hiding out in the jungle with only a small band of comrades. Fully convinced that the war was ongoing, Onoda and his brothers in arms stalked the island and adopted a harsh life in the wild. The group terrorised locals and prepared in vain for a Japanese counterattack that never came. Leaflets, newspapers, and even live radio broadcasts weren’t enough to convince the Lieutenant that the war was over, all dismissed as no more than cunning American lies designed to lure them out of hiding. Onoda would even brand his own brother as no more than an impressive enemy doppelganger, ignoring his pleas for him to leave the jungle and come home.

The quartet of soldiers slowly diminished over time: Yuichi Akatsu fled the group in 1949, while both Shoichi Shimada and Kinshichi Kozuka met their ends at the hands of the Lubang authorities in 1954 and 1972, respectively. After almost two years alone, Onoda was formally relieved of his duties by Major Yoshimi Taniguchi having been lured out of the jungle by the wannabe adventurer Norio Suzuki – the college dropout had set out to find “Lieutenant Onoda, a panda and the Abominable Snowman, in that order.”

There’s a definite tragedy in Onoda’s tale, with an argument to be made that the Lieutenant was a victim of the fascist regime that built him up as a weapon of war, only to be abandoned by his superiors – while search parties wandered for years, the army never formally made contact until the time of Onoda’s surrender. Arriving at Lubang at only twenty-three, Onoda missed out on the best years of his life by fighting for a lost cause. The Lieutenant ponders this wasted time in the closing lines of his memoir – “Who had I been fighting for? What was the cause?”

However, while there’s reason to feel sympathy for Onoda, he can just as easily be seen as a murdering tyrant who terrorised a generation of Lubang islanders. His account acknowledges the “requisitioning” of islanders’ goods and skirmishes with the police yet conveniently omits any mention of atrocities against civilians. As many as fifty Lubang islanders are alleged to have been killed by Onoda and his comrades, some in ghastly manners that can hardly be justified as mere acts of war. The Filipino perspective on Onoda’s story remains vital yet sorely unheard, as it’s easy to forget that for the islanders of Lubang, the soldier’s thirty-year war was their conflict also.

With so much to consider, it’s no wonder that Harari’s film clocks in at just under three hours in length. Rather than presenting a wholly accurate account of events, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle is instead frivolous with the truth. Such an approach allows for a more general character study of Onoda, opening up broader discussions on human morality and the importance of personal convictions.

An area of Onoda’s tale that Harari pays particular attention to is the Lieutenant’s relationship with Kozuka. The pair roamed Lubang together for close to eighteen years, forming a bond stronger than brothers as they stuck to a strict regimen. Harari focuses on the human element of this relationship, imagining a touching scene where the two bathe at sunset in the South China Sea. Jumping forward years later, we see the odd couple huddled together in a makeshift hut, giggling as they listen to the Apollo 11 moon-landing broadcast while seasonal rains thunder down from above. This brotherhood serves as the film’s heart.

Much like in Onoda’s account, Harari’s film highlights the delusion experienced by the Lubang holdouts, as they spurn the opportunity to go home several times in favour of pursuing futile resistance on the island. In one particularly telling scene, the Lieutenant and Kozuka plot out the “East Asian Co-Prosperity League” on a world map, fantasising about how geopolitics might have progressed. Choosing to believe in this fictitious alliance without a shred of proof suggests how desperate Onoda must have been to think that his efforts weren’t for nought.

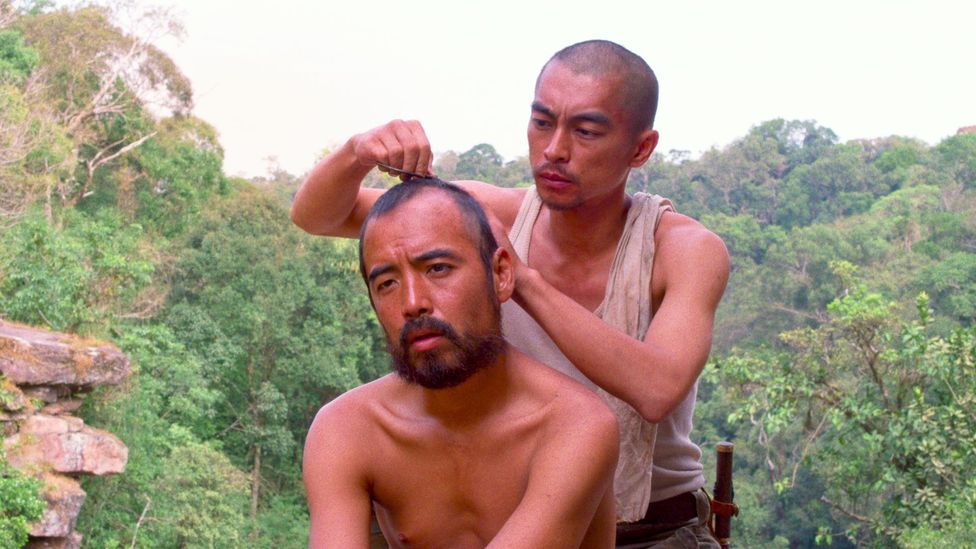

Harari has come under some fire for romanticising elements of Onoda’s story, yet the director doesn’t shy away from the Lieutenant’s crimes. An imagined run-in with an unfortunate islander seeking shelter from a tropical storm ends in tragedy, asking moral questions of whether Onoda was a principled man motivated by duty or merely an extremist soldier from a fascist regime running wild. Yuya Endo and Kanji Tsuda play young and old Onoda, respectively, the latter being unrecognisable in what is arguably a career-best performance – anime fans may recognise Tsuda as the voice of Trava from Trava: Fist Planet and Redline, while Endo starred as the titular Prince of Tennis in a musical theatre spin-off of the anime series.

Onoda’s case is made all the more interesting given that he was just one of many Japanese holdouts to surrender long after World War II concluded. Sergeant Shoichi Yokoi hid on Guam for another twenty years after finding out that the war was over, ashamed to turn himself and only emerging in 1972 after being overpowered by local fishermen – his message to the press upon returning to Japan: “It is with much embarrassment that I return”. There are even tales of holdouts outlasting Onoda, although the Lieutenant was almost certainly the last active Japanese soldier in South-East Asia.

Ultimately unable to adjust to life in a radically different Japan and certainly not accustomed to the fame and attention, Hiroo Onoda followed his older brother to Brazil, living out the rest of his life as a cattle farmer before his death in 2014. His remarkable story remains fascinating not just because of its improbability but also because it demonstrates the extreme lengths to which people are willing to take their convictions. Arthur Harari’s film is a fabulous introduction to Onoda’s tale, serving as a great starting point for those keen to learn more about the controversial man out of time.

Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle is released in the UK by Third Window.

[ad_2]